Typological inquiries

On Lori Anderson Moseman's 'All Steel'

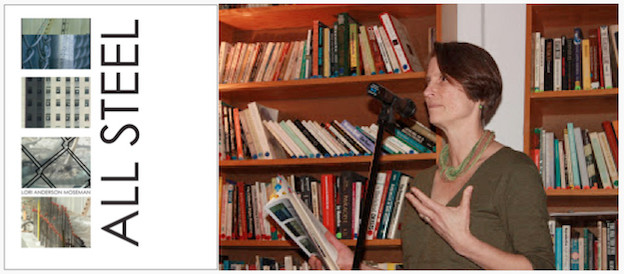

All Steel

All Steel

Made up of three sections — “Teaching Tools,” “Labor Pools,” and “Work Cycles” — Lori Anderson Moseman’s All Steel builds a complex series of cause-and-effect-like inquiries. These inquiries are based on a trio of typological metaphors: tool (is to) genre (as) type of worker (is to) building or social space (as) month or holiday (is to) ritual. The need to process events, experience, and empirical reality emerges as the impetus behind classification and naming.

Surrounded by excesses of material and sensorial information, these poems, and people in general, seek a means of organization and compression. Language itself is a means of shaping currents of thought. Here, tools, buildings, holidays, ritual, careers, and genres shape — All Steel highlights this correspondence.

Both the large metaphors and the titles highlight manmade classifications. Within the scope of objects and categories, form reduces the range of possible responses and actions. For example, in the case of a hammer, there is a way of letting the weight of the tool fall to avoid tiring one’s arm, the resistance of its form to a punching motion effectively prevents people from using a hammer in such a way. The subtleties of genre make it more difficult to define in any concrete way. Thus, by positioning it against tools, All Steel invites the extension of a tool’s capacity to dictate actions to the way that genre may dictate modes of writing.

Titles in All Steel seem to test specific versions of the text’s larger juxtapositions. Thus, the sum of these comparisons becomes most solidified in the table of contents, where we can see title after title positioning a tool next to a genre:

TEACHING TOOLS

| Harrow | Drawknife | Pulaski | Crooked Knife | Spar Pole | Pickaxe | Axe Handle | Core Bore(r) | Increment Borer | Drip Torch | Scalpel | Sawhorse | Paper Cutter | Hoof Pick | Spurs | Propeller | |

Melodrama |

Through titles that bring together specialized tools and genres of writing, such as a “Drawknife | Testimonial” or “Core Bore(r) | Oral History,” the table of contents makes typological and comparative strategies visible before one even arrives at the first poem. Divided by a vertical bar rather than connected by the conjunction “and,” or even the semigrammatical “ : ” or “ :: ,” the table suggests that connection and comparison will be performed as a spatial activity.

Within moments and spaces of excess, such as the traumatic death of a firstborn child, or walking across the aftermath of a forest fire, categorization and naming become most necessary. I get the sense that Moseman passes material, source texts, sensory information, and memory through a sort of invisible sieve. In the opening poem, “Harrow | Melodrama,” the title, minimal and typological, is the result of sieving:

Nineteen and nearly blind, she runs

across fenceless acres to her husband.

He and mule are at the plow. No.

He’s at the rake. No. Must be the harrow.

She’s just learning each season’s blade.

Unsure even now as she runs to him,

dead baby in her arms — their first.

When she reaches him, they become

one-winged birds destined to fly

as a pair — broken nest in their beak.

The ground below always in need

of breaking, of poking, pecking. (15)

Beginning at the moment when an excess of emotion bursts into the range of an unplowed field in the form of a “she,” the poem describes a trajectory and reaction between a husband and wife. However, before we arrive at the final image — “they become / one-winged birds destined to fly / as a pair — broken nest in their beak” — the poem runs up against a listlike sorting of farm tools: “He and mule are at the plow. No. / He’s at the rake. No. Must be the harrow.”

Tools are sorted and classified by the “she” racing, “nearly blind,” across the field. Functioning as a series of attempts to place herself, the tools recede only to reemerge, by proxy, in the final two lines of the poem as “the ground below always in need / of breaking, of poking, pecking.” By this logic, the work performed between the harrow and its operator becomes embedded within the tool.

The absence of actual melodrama in the poem and proximity of “Melodrama” to “Harrow” in the title invite the extension of this conception of a tool to the realm of genre. The similarity of the plow, rake, and harrow, plus the possibility of mistaking them for one another — all three instruments mentioned in the poem are designed to tear through and loosen the topsoil of a field — call to mind the subtle distinctions between classifications of writing. Often overlapping and borrowing techniques from one another, genres function as tools in a space of writing by laying down a series of general expectations. These expectations allow some questions to go unasked; some possibilities go unexplored.

To the extent that a tool is designed to perform a particular function, it restricts and calls for particular actions — there is a proper way to drive a harrow or to swing an axe. Overwhelmed by material, text, sensorial experience, and memory, genre can function as a filtering tool by which the excesses can be processed and sorted. And indeed it is almost through genre or choice of a tool that one may begin, literally, to handle that which overwhelms.

Moseman’s frequent use of two-column structures also functions as a filtering mechanism. However, in these, connection is made where the poem seeps across the right margins of the column to bleed into the other. A reader is always faced with the desire to read both columns at once, but due to the impossibility of doing so, must settle for reading each poem twice — once moving left to right across the margin of the columns and again reading down each column — as in “First Tools | Fairgrounds”:

2nd wave [1978

axe – the first tool we’re issued on site

then, a rusty file to sharpen our blade

steel on forged steel – a skinned knee

we stroke unidirectional to the edge

drought hills our brittle California gold

we whittle underbrush arbutus strung out

we whack all day & boys stalk our thighs

count out militia songs hurl insults

until we swing a labyris their way

backlash [2004

cane – the first tool we’re issued at home

the one granddaddy broke to poke his bore

tap tap we girls with our champion gilts

move them slow in front of the judge slap

the jowls the front quarter bruising shows up

on white pigs on a Hampshire’s white stripe

that thin beauty queen sash on a shoulder

roast) future farmers we parade market hogs

for the joy of slop and being singled out (41)

Parallel descriptions come together here despite, or perhaps because of, the length of time between 1978 and 2004. Beginning with two tools, the lack of punctuation (other than several em dashes) suggests that one might read each column as distinct until the sixth line, which runs over into the right column. The way the smooth left margin is displaced by the interference of the first column indicates that the line might have merged or have been replaced. Even if reading across the margins had not occurred to us before, we must do so now, and it’s as if an unnerving echo has introduced itself into the poem. When reading across the columns, we’re faced with parallel sentence structures and a sense of call and response at once.

It is a slippery sense of relation and commonality which All Steel builds in this poem. Leaving this reader tantalized, the text constantly eludes — there is always the possibility of something else, something one’s missed. The complexity of the work as a whole, with organizational and classifying structures shaping on several levels, and its innovative use of titles, keeps me diving in again and again — if not to grasp, then to be within the moments of these poems again.