Through and never through

On Peter Cole's 'The Invention of Influence'

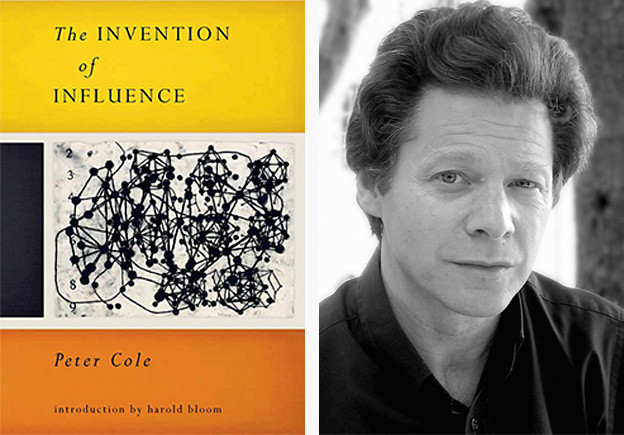

The Invention of Influence

The Invention of Influence

Peter Cole’s writing exemplifies Charles Olson’s notion that the poet is a transfer station, and that the poem “is energy transferred from where the poet got it (he will have some several causations), by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader.”[1] Cole channels his own poems’ “several causations” through his experience as a journeyman translator of Hebrew and Arabic language poetries, modern and medieval. If poetry is the scholar’s art, according to Wallace Stevens, then Cole’s work begs the additional question: what if poetry is also the translator’s art?

Cole has written his fourth book of original poems through the core concept of influence. The proximity between influence and translation is something Cole once remarked upon when introducing Selected Poems of Solomon Ibn Gabirol, his translation of the eleventh-century Andalusian Jewish poet-philosopher. “Translation,” according to Cole,

particularly in an age of translation, is not only what hired or inspired workers have rendered into another language; it is also what writers who read in multiple languages translate in thought alone — the force of which is brought to bear on the written language they use. This, granted, is simply influence; in this instance, however, it is influence born of a steady passage across linguistic and regional borders.[2]

Cole’s own poetry comes to us across the porous borders where “thought alone” is formed by all of the languages he knows — traditions which give thought its bearings, music its glossaries, tone its inflections. “Great genial power,” wrote Emerson about Shakespeare, “consists in not being original at all,” but “in being receptive.”[3]

Paired with his previous collection from New Directions, Things on Which I’ve Stumbled (2008), Cole’s book reestablishes him as one of the most receptive poets writing today. His capacity for conducting his own source influences into poems of quiet, philosophical astonishment is something quite riveting. The Invention of Influence is an affirmation of influence, of the strange joys of being “afloat in the foreign.”[4] It offers a corrective to the tragically egocentric anxiety of influence that led the psychoanalyst Victor Tausk (the subject of the book’s long title poem) to kill himself and Sigmund Freud to suppose that “it is one man, the man Moses, who created the Jews.”[5]

The influence of Kabbalah

Only by sucking, not by knowing

can the subtle essence be conveyed[6]

— “Improvisation on Lines by Isaac the Blind”

Emerson began his essay “Quotation and Originality” with this odd and wonderful image that reminds me of the attractions and pleasures of Cole’s scholarly temperament:

Whoever looks at the insect world, at flies, aphides, gnats and innumerable parasites, and even at the infant mammals, must have remarked the extreme content they take in suction, which constitutes the main business of their life. If we go into a library or news-room, we see the same function on a higher plane, performed with like ardor, with equal impatience of interruption, indicating the sweetness of the act.[7]

The greatest succor to be drawn from Cole's new poems comes through his immersion in the poetics of Kabbalah. In 2012, Yale University Press published The Poetry of Kabbalah: Mystical Verse from the Jewish Tradition, a breathtaking anthology of poems spanning the sixth to the twentieth centuries, all translated by Cole. Kabbalah is itself a vast and bewildering invention. One way that it approaches an unapproachable Godhead is by musing on the surface tension of language, the literal letters of the alphabet which combine to form what Marianne Moore once called a “precipitate of dazzling impressions, / the spontaneous unforced passion of the Hebrew language.”[8] “Actual Angels,” an early poem in Cole’s new collection, imagines letters as angels whose messages are decipherable only in passing, in gaps, seams, and margins.

1.

Are angels evasions of actuality?

Bright denials of our mortality?

Or more like letters linking words

to worlds these heralds help us see?

2.

It’s the freighted angels that elevate.

Opaque with their burdens, they wait

for someone to sense what’s there, between,

until they’re released to the weather again.

3.

Gone is the griffin, the phoenix, the faun.

Only angels in the poem live on

as characters catching the light between things,

as carriers of currents from the wings

of thinking we know where we’re going and then

getting somewhere, despite our intention. (5)

Cole’s disposition is Midrashic, and his exegeses run edgewise. Words don’t illuminate meaning — they insinuate it in glimpses, tears, rumors. Above all, meaning is relational and intertextual.

8.

Angels are like letters, says Abulafia,

in us like mind as the present’s hum.

No one knows what a year will bring,

but the world-to-come is the word to come. (6)

At other times he reads the natural world in the secret key of Wallace Stevens:

12.

The elm slides liquid leaves through its sleeves —

its twig-tips swell with a ruby-like glow;

seraphs of jade then crown this mage,

their wings spreading the shade we know. (7)

No poet so resembles Stevens’ attachment to supreme fictions, or so approaches the celestial pantomime of Stevens’ music: restlessly experimental, but couched in traditional prosodies. Stevens invented an idiosyncratic lyrical substitute to fill the vacuum left by the departed gods. Peter Cole’s supreme fiction is likewise supremely fictional, but his engagement with Jewish textuality makes it a shared and traditional fiction: communal, historical. The elm looming above might sound Stevensian, but this is no solipsistic palm at the end of the mind. Cole is tracing the Kabbalah’s image of an upside-down tree whose roots are in heaven and whose leaves and branches swing low into the actual world.

Cole employs a range of poetic methods derived from Kabbalah, including acrostic poems and invented forms structured by images of the sephirot, the ten emanations of the Godhead. Throughout, Cole aspires to what Kabbalists call tikkun: the restoration of the fragments scattered by the original catastrophe of creation. His strophes imagine a repairing that is both cosmic and interpersonal. By Cole’s lights, a poem is

… that which hovers here

between the “I” of the opening

and the “us” of your possible listening

now, or in the imperfect

tense and tension of what

in fact articulates the eternal

That abstract revelation

and slippery duration

to which, it seems, I’m given

and because of which I’m never

finished with anything, as though living

itself were an endless translation (4)

Translation is a metaphor for a special kind of longing for the other. It anticipates a state of eventual arrival, reception, and completion. But this “word-to-come” is imaginable only through the provisional flowering of slippery word variants, deciduous syllables, the poet’s makeshift decisions, the reader’s temporary gleanings.

Influence in psychoanalysis

The book’s central title poem forms a decisive and fascinating counterpoint. It is a meticulously forensic reconstruction of the life and death of Victor Tausk, one of Freud’s most promising, but most troubled, disciples in the early years of psychoanalysis. After killing himself in 1919 at the age of forty, Tausk was fated to become a tragic footnote in the history of psychoanalysis, chiefly remembered for his paper “On the Origin of the ‘Influencing Machine’ in Schizophrenia.”

Reading Cole’s masterful, polyphonic orchestration of the Tausk-Freud relationship (the poem is fifty pages) feels like experiencing the slow, inexorable slide of Greek tragic drama. This fateful tale is the opposite of Cole’s cherished open-endedness, for the death of Tausk is such a foregone conclusion. Rather, Cole offers us a formally gorgeous, if painstaking, account of the dire consequences that result from the pathological desire for originality and the fear of influence.

Cole mobilizes a vast array of textual resources to do so: he draws on Tausk’s own writings (letters, papers, poems, journals), on Freud’s letters, on the journals and letters of Lou Andreas-Salomé (who had a brief affair with Tausk and entertained a long friendship with Freud), and relies heavily on Paul Roazen’s book Brother Animal, an excavation of the Tausk-Freud relationship which largely blames Freud’s rejection of Tausk for the younger man’s suicide. Freud felt threatened by his student’s pioneering work, Roazen argues, and probably felt other more personal aversions as well, leading him to disown Tausk in a calculated move that partly contributed to the disciple’s death.

“The Invention of Influence: An Agon” opens in a voice that recalls the premonitory authority of the chorus in Greek tragic drama. The prefatory poem is drawn from Tausk’s paper on the “influence machine” which controls the thoughts and feelings of the paranoid schizophrenic:

… Boundaries are called into question

as though one’s thoughts were “given”

and knowledge implanted from beyond —

so what’s within is known.

One does nothing on one’s own.

Strings are pulled and buttons

pressed, all to evade an anxiety

that rears its head at the heart

of the void in avoidance. The echoes begin:

The cure as illness, the illness

as cure. Thus the revolving door

that becomes a lament for the makers —

and for those who fall prey to the powers —

of this most intricate machine. (32)

Later, Cole parses Freud’s own thoughts about the ways in which a writer may think he’s doing original work when actually he’s just repressing the sources from which his ideas originated (an anxiety Freud himself possessed most acutely).

Precisely this

afflicts the plagiarist,

or something like

the X he is:

What’s old and has

long been known

seems to him new

and becomes his own.

He’s all reception,

all alone,

and the fruits are manifold

though the root is one —

thwarted ambition

and a sense at heart

the doctor describes

as a kind of cry:

I cannot bear

not to have been

the first to have uttered

a certain thing. (56–57)

Both Freud and Tausk suffered this anxiety with respect to their work — and of course, aversion to influence is a cornerstone of Freudian psychoanalysis in general, with its fixation upon the Oedipal dilemma that leads the son to attempt to murder his father.

That I am a son, said Tausk,

around the time he encountered Freud,

causes me great embarrassment

(it shames me)

when someone calls me by the name

handed on by my father ...

because a father conceived me

and a mother brought me into this world.

Destiny’s what the eyes can see,

the ears take in, the hands contain —

and still we’re called to account with the elders,

and blood misled, misleads again.

And so with a needle he pierced

that picture’s heart —

his mother

on the wall (33)

The subtitle of the poem, “an Agon,” reminds us of Harold Bloom’s writing on the agonistic aspects of influence, and of the Freudian underpinnings of his theory. In his book Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism, an elaboration of ideas first established in The Anxiety of Influence, Bloom insisted that

the love of poetry is another variant of the love of power … a particular power, the power of usurpation…. We read to usurp, just as the poet writes to usurp. Usurp what? A place, a stance, a fullness … something we can call our own or even ourselves.”[9]

This viewpoint, so bent upon claiming a fixed place for oneself, is quite incompatible with Cole’s essential poetics, which practices writing as a form of translation, as a “being between” fixed places, with the poet as a transponder, not an orator, a conduit, not a usurper.

Nevertheless, Bloom’s misprision hovers over Cole’s interrogations of influence because his introduction to the book offers such a strong reading of Cole’s importance. Bloom rightly praises Cole for producing “a specifically Jewish self somehow centered upon translation, with that process reconceived in a sense both broad and cutting” (xi). However, he misreads Cole when imagining a hidden affinity between Cole and Freud:

Our Father Freud fully expected to replace Judaism with psychoanalysis, and the man Moses by the man Solomon Freud. On one level, Cole wonders if the American Jewish poetic quest can evade some affinities with the audacious Freudian project. (xi)

In fact, Cole is not at all driven by a desire to write poetry that is either originally American or originally Jewish. The strength of Cole’s work is partly its eschewal of what Louise Glück has called the “imperatives of self-creation,” American literature which seeks to “break trails, to found dynasties.”[10] For Cole, as for all Kabbalists, “creation” is something divine and unknowable. Writers don’t create. Poet-translators invent; they translate; as often as not, they are “driven by the pulse of another’s poem” (90). They find rather than found.

In the end, Cole bookends the “The Invention of Influence: An Agon” by presenting two slightly different versions of the same poem at the beginning and at the end, as if to contain or to quarantine this Oedipal drama, to prohibit Tausk’s nightmare from taking effect upon us, lest the following equation come to define us:

I.M. — an Influence

Machine, in short;

and we are what we

become in its import. (64)

Towards the ecstasies of influence

“I.M.” is a parody of the “I AM” of the Hebrew God whose influence Jewish writers have invented and reinvented down the centuries. Cole follows the Freudian tragedy with his rendering of a seventh-century poem by Yannai, one of the first writers of liturgical poems in the Jewish tradition. Under the title “On What Is Not Consumed,” Cole translates:

Angel of fire devouring fire

Fire Blazing through damp and drier

Fire Candescent in smoke and snow

Fire Drawn like a crouching lion

Fire Evolving through shade after shade

Fateful fire that will not expire

Gleaming fire that wanders far

Hissing fire that sends up sparks …

For Cole, the Jewish mystical imaginary effectively burns off the Romantic’s anxiety of influence. The burning bush is the source of all language for Jewish mysticism. And indeed, Cole understands ordinary language itself — however it comes to us — as the sacred origin of influence.

Poets renew its “normal magic” whenever they sit down to restoke its fires, to bank its light and its heat. In this way, Cole’s ongoing invention of an English-language Jewish-Kabbalistic poetics demands that he continue becoming traditional while remaining what he is: a thoroughly experimental connoisseur of bewilderment and errancy. The project is open-ended, its undertaking is never through. Toward the end of the new book, “The Perfect State” reminds us of this in many ways:

1.

The perfect state of being human isn’t perfection,

it’s becoming, the Greeks say, ever more real

in nearing but never quite reaching a certain ideal,

like translation. It’s deficient. A chronic affection.

2.

Perfection for the Kabbalist is reached

only when the fortress is breached

to the brokenness, the husks, the Other Side.

so imperfection becomes a guide (88) [...]

5.

Perfection, the feeling philosopher says,

suggests an openness to endless change—

the self in radical revolution

within a self it soon finds strange. (89)

With The Invention of Influence, Cole turns the “radical revolution” of American poetry in new directions, writing with the same spiritual ardor, the same skepticism, and the same sublime craftsmanship that illuminates the work of the illustrious company he shares most: Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, Susan Howe. He enlarges American poetry considerably, too, by demonstrating the kindred spirit shared by the Jewish mystical imagination and the restless agnosticism that defines the best of all our contemporary poetry.

1. Charles Olson, Collected Prose, ed. Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 240.

2. Selected Poems of Solomon Ibn Gabirol, trans. Peter Cole (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 23.

3. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays and Lectures (New York: Library of America, 1983), 711.

4. Peter Cole, The Invention of Influence (New York: New Directions, 2014), 90.

5. Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, trans. Katherine Jones (New York: Knopf, 1939), 168.

6. Peter Cole, Things on Which I’ve Stumbled (New York: New Directions, 2008), 3.

7. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Quotation and Originality,” Emerson Central, March 22, 2014.

8. Marianne Moore, The Poems of Marianne Moore, ed. Grace Schulman (New York: Viking, 2003), 153.

9. Harold Bloom, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 17.

10. Louise Glück, “American Originality,” The Threepenny Review, no. 87 (Fall 2001): 9.