'A speck of behavior, a fleck of culture'

A review of 'Field Work: Notes, Songs, Poems, 1997–2010'

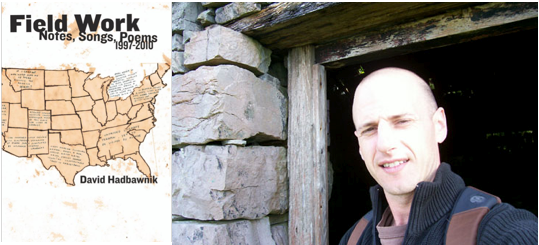

Field Work: Notes, Songs, Poems 1997-2010

Field Work: Notes, Songs, Poems 1997-2010

When Henry James wrote about “the state of the streets” in American cities at the turn of the twentieth century, he expressed over and over the difficulty of ever doing justice to the task. Faced with “a welter of objects and sounds” James in The American Scene claimed his powers of perception to be in such disarray that the semiotics of American manners eluded his grasp almost completely.[1] For James “there couldn’t be any manners to speak of” in cities defined by such violent congestion, such “unmitigated publicity, publicity as a condition, as a doom, from which there could be no appeal.”[2]

In his new book Field Work, poet David Hadbawnik rises to the challenge that possessed James, as it has occupied so many literary ethnographers of American cities. Hadbawnik succeeds exactly because he hasn’t tried to summarize our patterns of public behavior, or to narrate cultural “truths.” As Clifford Geertz once wrote, “There are enough profundities in the world already”[3] Hadbawnikcaptures instead the most ephemeral surfaces of daily behavior, the tiny gestures and the subtle, split-second glances that communicate the ways in which we communicate with and avoid communicating with each other in public. Whereas James wanted to place the American scene into proper perspective, Hadbawnik jots the world down in the instant it peels off.

The urge to catch things, to save them from falling; first it was the leaf tumbling down as I walked to the bus stop, then it was the woman falling back in the aisle as the bus pulled away[4]

Hadbawnik’s notebook procedure is naturally well adapted to this urge. If Dziga Vertov assumed the task of the “man with a movie camera,” documenting social reality from a heroic perspective, Hadbawnik is that most unassuming man with a pocket notebook, looking out the window of a public bus stalled in perpetual traffic.

The woman made both of her dogs, huge Rottweilers, heel and sit on the curb even though the light was green. As soon as they sat, she got them up and hurried them across the street (64)

Such notations of “the ordinary” do what poetic writing has always tried to do, since the days of Imagism forward — to arrest the world in its tracks. But as soon as one enters the first pages of Field Work, a strong historical undercurrent becomes immediately apparent. The majority of Hadbawnik’s observations inscribe themes of surveillance, of authority and control, of menace and premonition. Although the woman at the intersection is innocently enough training her dogs to heel, in the context of Field Work her orders acquire a vague feeling of injustice. There is something rather arbitrary, the reader feels, even insidious about the dogs being “made” to heel, then suddenly made to hurry across the street, according to the whims of their master.

A similar feeling hovers around this observation, dated July 23, 1997:

Man puts calico cat into passenger side of a pickup truck, then walks away. (13)

Why should the man’s action feel weirdly hostile, as if a kidnapping were taking place right under our eyes? The entirety of Field Work is taut with this barely suppressed violence, its candid observations shot through with feelings of suspicion, distrust and paranoia.

I notice it again as we’re all forced to transfer onto a new bus — that urge everyone has to sit in the exact seat on the new bus — which I’m unable to do because somebody’s already sitting in mine. Everyone looking around at first to check their relative positions. (12)

Hadbawnik’s need to “look around” is thus a far cry from the detached aesthetic interest taken by the flaneur or the urban haiku-seeker wandering through more temperate surroundings. In millennial cities divided by poverty and homelessness, public space is an agonistic, highly contested arena. Keeping one’s eyes peeled becomes a necessary habit, a technical means of survival. Everyone is always potentially guilty, in Hadbawnik’s version of the city, of crimes that no one has committed.

When I saw two young hoodlum-types walking towards me on my street, snickering in a suspicious way, I tried to observe them very carefully, as though I might have to describe them later to a police sketch artist (24)

If a culture of surveillance implies that we are all guilty until proven innocent, then this condition, most importantly, involves the observer himself. In Field Work the act of watching is itself a “suspect” act, for the gaze infringes helplessly upon other people’s “privacies.” To size up others is to assert power, and to have power is to be prey to others’ suspicions.

As I wait for a bus on the corner of 18th and Mission, a small, tough-looking guy with his hair tied back in a ponytail walks towards me, catches my eye, and mutters, “You stand there staring at people someone gonna think you a cop.” I say nothing. A little while later he passes me again with a hard stare, muttering under his breath; meanwhile, everyone nearby looks at me distrustfully (24–5)

We are indeed a long way away from “petals on a wet, black bough.” Field Work is less given to moments of undistracted beauty and transcendent perception than it is interested in registering those moments when, as Nietzsche once said, “the soul squints.”[5] The all-too-human affects of anxiety, disgust, anger, hatred, impatience and aggravation may be feelings that one is not particularly proud of, though they pervade our daily lives.

I sit down at a table in the library. The man behind me glances up sharply, which I take as an admonition to keep quiet, so I softly unscrew my soda and munch quietly on my snack. But after a few moments, it begins: first he crumples up several bunches of papers, then rises noisily to deposit them in the trash, comes back, groans, stretches, sits down, sings to himself, moves pencils and papers around, handles a business envelope, crinkling the cellophane window; scoots his chair in and out. Quiet for a moment. Then, noise again. On one of his passes he looks into my eyes as if sizing me up, seeing how much I can take (30).

The wonder (and so often the humor) of Hadbawnik’s writing follows from the meticulous but nonchalant precision with which he documents such a wide variety of incidental encounters.

I hated the man with the little electronic device for the knowing smile that turned up the corner of his mouth as he glanced around on the train (106)

Because of his interest in recording moments of sudden ressentiment, Hadbawnik participates in a poetic tradition that one most immediately associates with Poe and Baudelaire. Indeed, the earliest portions of Field Work were first published in a chapbook entitled SF Spleen, published by Skanky Possum in 2006. A quieter, less melodramatic version of Baudelaire on the prowl in Paris Spleen, Hadbawnik’s observer both suffers and enjoys the poet’s “loss of a halo.” Like Baudelaire, he has become “bored with dignity.”[6]

This boredom clears the way for him to notice details like the texture of dog shit — “rich red-brown, often with undigested bits of food in it, beaded, sculptural, coming out in little balls or ‘soft serve’ in one big bubbly lump, warm in my hand through the plastic bag” (93). More importantly, it allows him to attend to the various indignities his own (male) gaze imposes upon others.

I watch the girl with big eyes walk out of the café and across the street, and I feel a twinge of embarrassment that she might be going to the same performance I am, since it was my staring (I think) that made her put her sweater on over her blouse (79)

Whereas Baudelaire claimed that the poet, having lost his halo, could now go about “incognito,” this is certainly not permitted Hadbawnik. “I regret to say that I have not yet become totally unrecognizable, totally inconspicuous,” reads one of Field Work’s epigraphs, from Peter Handke’s The Weight of the World (9). The erstwhile goal of the modern ethnographer — to be a transparent eyeball documenting life from a distance — is not a goal to which Hadbawnik aspires.

In fact, one must conclude that the opposite condition obtains. Field Work aims to expose itself as a primary cultural document — not simply a work of secondary critical reflection. This notebook demands to be experienced as the “confessions” of a serial notebook writer. “Every move / you make is on / the jumbotron, / and the stadium’s filled,” reads the beginning of an unwritten poem (115). Indeed, the second half of the book is littered with the drafts of aborted poems, one-off story ideas, scraps of song lyrics — some dark and acidic, some funny and light — all presented in the raw.

The body is merely

a kiss

but a kiss that

encompasses the

world; a glance

a flash of skin.

a gesture, a lock

of hair blown

out of one’s

eyes, an eye

expanding into

a pair of lips,

a tongue

a voice

but I am a ghost (108).

“Americans have an inexorable urge to be confessional,” Hadbawnik at one point quotes Lyn Hejinian, “but they seldom speak confidentially, preferring to be overheard” (35). Like so many great notebook writers before him, Hadbawnik displaces the performance of private speech with the performance of confidential writing. The ghostly intimacy of Field Work reminds us of how the notebook genre enacts writing’s very own dream of itself — the construction of a habitable space that offers the itinerant writer a utopian version of “home” in the midst of the point-blank violence of an indifferent world.

Interestingly, throughout Field Work the only people who are exempt from the humiliations and impositions of the public gaze are those workers engaged in physical activities. Hadbawnik reserves his most romantic writing for descriptions of manual labor, such as a man painting San Francisco’s Polk Street station in the middle of the night.

He reaches about five or six difficult spots, the corners where bars meet, the backs of beams, without ever shifting his feet. Every movement slow but efficient — he dips the roller in the bucket again and plunges it up and down, and a thin sheen of sweat glistens on his skin. Table saws buzz, a dozen co-workers clomp and scrape about him, wet paint reeks in the cold night air, and a halogen lamp throws his shadow up the sides of the structure (22)

Such passages seek redemption in routine, exacting, everyday actions. The painter has an inalienable practice that permits him a temporary escape from the glancing blows of the world. Whenever Hadbawnik describes construction workers patiently laying a concrete foundation, or a hockey player maneuvering swiftly down the ice, he is also alluding to the emancipatory potential of a daily writing practice. We write, in part, to lose ourselves in the work of composition, in the choreographies of sentences, in the patterns and variations of phrases that make writing a profoundly formal pleasure.

One wants to keep reading this notebook, which spans the years 1997–2010 and a series of cities from San Francisco to Buffalo, for the simple reason that the miscellany saves each moment’s notice with such grace. Its highly irregular, ephemeral character accentuates each passing pleasure considerably. The fact that the notebook is a very fragile form of expression, for it could be abandoned or interrupted at any moment (“many oases of inactivity,” reads one entry), only reinforces the sense of free agency that accompanies “non-productive” modes of writing. Field Work’s intermittent, catch-as-catch quality echoes the question that Baudelaire asked himself, upon shifting from the idealized genre of poetry to the unclassifiable, accidental, seemingly endless mode of notating modern life in the format of prose poetry: “Why carry out one’s projects, since the project is sufficient pleasure in itself?”[7]