On textual cohabiting

Jocelyn Saidenberg's 'Dead Letter' and Brandon Brown's 'Top Forty'

Dead Letter

Dead Letter

Top Forty

Top Forty

What are the ethics of citation? Don’t all poems enter into the cacophony and babble of “the great conversation,” or to mix metaphors, that river of text, of jetsam and flotsam we all swim in and against? Still, to take up a gentle anachronism, we might ask, who sits at the table, and what is the etiquette of the host? How do you turn to your citation-guests? What do you offer? Two recent books, very different in subject matter and affect, take up this question — as both are explicitly addressed to other work(s) of art, inviting them, as it were, to the table. These reflections were first written on the occasion of hosting Brandon Brown and Jocelyn Saidenberg in Toronto at a reading of the Contemporary Poetry Research Group, organized by Mat Laporte, navigating through the tricky and wonderful territory of hosting and guesting: intimacies and disappointments, a stopped toilet, a rainy day, and a dumpling feast.

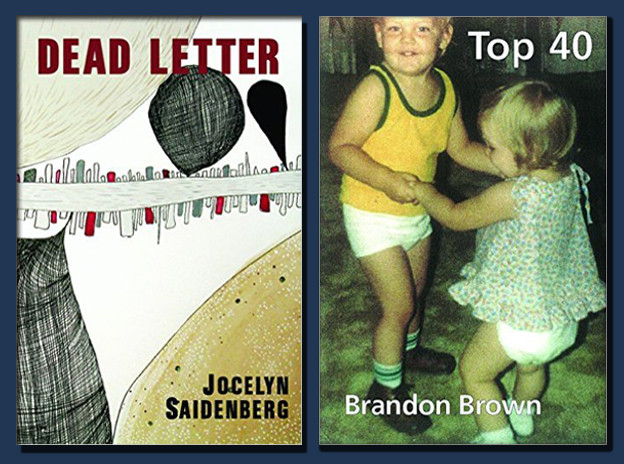

Dead Letter is a kind of rewriting of Herman Melville’s strangely opaque short masterpiece, “Bartleby the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street.” To remind you of the plot in a nutshell: it is a story about Bartleby, a law clerk whose main job is to recopy documents. One day he is asked to work and says that “he would prefer not to.” The rest of the story is about the narrative and metaphysical consequences of that refusal. Top Forty is also an extended critique, an ekphrastic meditation on pop songs, proceeding from the fortieth song to the first song on American Top 40 with Ryan Seacrest, September 14th, 2013.

In his last poem, Brown refers to “the long history of artists repeating, recycling, reusing other artworks in order to become less confused about their own art” (135). More words for artistic recycling: allusion, intertextuality, ekphrasis, rewriting, anxiety of influence, fan fiction, appropriation, translation. This recycling can read like mastery: I know you, pop song, Grecian urn, autopsy report, better than you know yourself! I can explain you, I can capture you, I can pin you down, boil you up, and render your essence. I can make money off you. In the same poem, Brown talks about a specific kind of mastery: “the long history in the US of white appropriation of black art, which regularly elides the visibility of that appropriation” (135). Together with this problematic implication of mastery, there’s also a sharp kind of sense of loss that lingers around the edges of these artistic projects. Anxiety that it won’t be as good as the original, that the copy can never be as vivid as the real thing. Poems are never as colorful as paintings, never as fun as a song that makes you want to get up and dance.

Both books take these two dangers into account as they proceed — but their main business is neither mastery nor loss. It’s something else, and I’ve been trying to find the right words for it — alchemy, making the space bigger, redeeming the sparks, if you want to get all Kabbalistic about it, or to say it really simply:love.

So let me be a little more specific. Melville wrote his story from the point of view of Bartleby’s lawyer-employer, and Saidenberg’s first big shift is to give Bartleby a first-person voice. However, in Dead Letter we still don’t get the exposé, the untold adventures of Bartleby, which would help us resolve the opacity of Melville’s text. Rather, Bartleby’s first-person narrative actually recopies many of Melville’s words; Saidenberg is more aligned with the job of scrivener than author, copying Melville’s words into her own text. Besides copying his lawyer’s documents, Bartleby is also given the task of proofing his work and checking the accuracy of his copy. In Dead Letter, we ourselves are also turned into these copyeditors/scriveners because we end up comparing the Saidenberg and Melville texts to each other, looking for discrepancies in the copy.

I’m writing this introduction surrounded by screens and by texts, sitting in a small office. I just read a piece in McSweeney’s on the snake-fight portion of your thesis defense. It was pretty funny. My phone beeped. I’m chatting with my partner about movie tickets while at the same time watching a video without sound of masked Israeli soldiers waking up a Palestinian family at three a.m. to ask their kids if they throw stones. Reading Ron Silliman on Kenny Goldsmith, Stephanie Young on Kenny Goldsmith, photos from National Puppy Day, apologies from the Israeli left for not winning the elections, a woman beaten to death in Afghanistan, advice on how to give away fares with your metro card on the new York City subway — this is the place we all live in, gorging all day on text, hemmed in by text, all of us like Bartleby hunched over his copying.

And yet something happens to Bartleby’s stifling geography in Dead Letter. It’s all about the accumulation of tiny transformations. Saidenberg’s Bartleby pushes at his text, moment upon moment of heavy lifting, hard labor (as Christian Nagler describes it in the afterword), until he cracks it open, until the paltry life Melville has given him is made wild, and the chambers seem to reveal a hidden Atlantic ocean inside them. For example, in the Melville story, the lawyer describes his claustrophobic Manhattan offices: one window looks out onto an air shaft, the other window has a brick wall for a view:

Owing to the great height of the surrounding buildings, and my chambers being on the second floor, the interval between this wall and mine not a little resembled a huge square cistern.[1]

More or less the same text is copied into a prose-poem Saidenberg calls “Our Habitats.” Listen to her lines, or to her Bartleby speaking:

the interval between the chamber’s windows and this wall not a little resembled a huge square cistern, from which in a pastoral scene, a shepherd might water his flock (25, emphasis mine).

When Bartleby is given a voice, our spatial imagination expands a little beyond the lawyer’s chambers — the suggestion of water, sheep, the enormous care taken by shepherds, the meetings that can happen at cisterns. There’s something deeply ethical about this act of cohabitation with a text, with a character, which is also a function of spent time; this is not a dashed-off copy, but the most careful years-long record of scrivening.

Perhaps because Bartleby is so lonely in Melville’s story, I tried to think up literary relatives for him: Shakespeare’s Cordelia, who wants nothing from King Lear; Kafka’s hunger artist, who will fast until he dies. As I read Dead Letter, though, I came to relate Bartleby to one of the most vivid of biblical characters, preserved in the amber of the so-called dead letters of the Old Testament. Part of Dead Letter’s alchemy is to make you feel that all of that richness of Bartleby’s inner life was already in the Melville text; you just have to be looking really closely. You have to really devote yourself to the language, to cling and to cleave. Jocelyn Saidenberg reinvents Bartleby as a figure of cleaving, who devotes himself to his lawyer and his refusal. In that sense, I think Dead Letter gives Bartleby another literary relative — or maybe she was there all along in Melville’s biblically haunted text — and that is Ruth, who loses everything in a famine, but queerly cleaves to her mother-in-law Naomi, and in her persistent cleaving becomes a figure for redemption.

Flickers of redemption can be found in the most unlikely places: in addition to being about one week of top-forty pop songs, from “Take Back the Night,” to “Blurred Lines,” Brandon Brown’s Top Forty is also about Icelandic epic, the great advantages of baths, addiction, political strategies, how you know things, movies from the eighties, death, the end of the world, capitalism, and friendship. It is also about time, but it’s not elegiac about the ephemeral nature of pop (and poop) and fashion and bad movies, as the blurred childhood photo on the front cover might suggest. Well, not only. In summoning up these ephemera, the stray thoughts you have while you pee, the things friends say to you, little vanities, crumbs of philosophy, I think Brown is doing something with a bit more of a kick.

Ok, well, I’m just going to say it: in Top Forty Brandon Brown is “seizing up the past as an image that flashes up at the moment of its unrecognizability.” That’s from Walter Benjamin, who also says “Fashion has a nose for the topical, no matter where it stirs in the thickets of long ago; it is the tiger’s leap into the past.”[2] What Benjamin is describing is the task of being so deeply inside the present moment, in fashion, and architecture, and cafés and the clichés of pop music, really immersed in it — in what he calls now-time — like putting your whole body into a warm bath — that you can see something important, something that will make the continuum of history explode. It’s flaring up and flashing by, so you have to catch it.

Benjamin’s metaphor always reminds me of the anxiety you get at a sushi-boat place when you see something you really like going by but you don’t get it in time, but this is happening about five times faster, and the little plate has the meaning of life on it, or at least a message from your long-lost lover. Brown’s trying to crack it open, and the only way to do this is with devotion, a shipwreck that comes from refusing to abandon the gaudy, boozy party-ship. There are moments of exquisite irony in applying philosophy and grammatical analysis to these songs, but even here Brown shies away from mastery, reminding us “I’m not just taking a cheap shot at Macklemore, / I’m implicated in this totally, as you know by now” (81).

In Benjamin’s famous fragments on the concept of history, he addresses the task of the revolutionary historian who must reveal the histories untold by the winners. Well, that’s not quite what’s happening in Top Forty, which sometimes reads as an address to a musical version of the dollar store, full of desirable plastic. But Brown subjects this plastic ephemera to a kind of rigorous, radical, and revolutionary philology, in the sense of the love and friendship at the basis of the logos.

Let me quote an example of this revolutionary philology in full. In discussing Ice Cube’s metrical innovation, he says, “it is an exemplary instance of very regular measures surrounding quick tribrachs of hurtling syllables, broken up by the lightest stresses, light as a mosquito’s proboscis” (135). Brown’s precision about language, about metre, is mixed with a precision about affect, about the touch of language on the body, which is itself a swoon of a sentence, a sweet and heady cocktail. But it is also, finally, a generous and humble hosting of Ice Cube’s oeuvre. In Top Forty Brandon Brown is throwing a philology party, and you’re all invited to drink and be merry and break open the continuum of history.

1. Herman Melville, “Bartleby the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” (1853), 5.

2. Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings Volume 4 1938–1940, trans. Edmund Jephcott and others, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 390, 395.