Pretty information

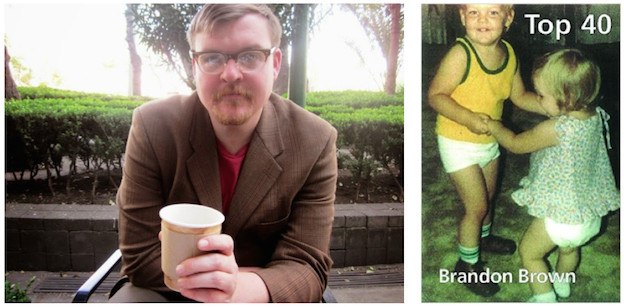

A review of Brandon Brown's 'Top 40'

Top 40

Top 40

Brandon Brown’s Top 40 is forty poems of forty sentences, each sequentially titled with the name of a song from America’s Top 40 with Ryan Seacrest, where the first poem’s title is the fortieth song of the countdown on September 14, 2013, and the title of the last poem is number 1.

Pop music is an ecstasy for Brown, and it has both collectivity and isolation in it. He writes:

Every Sunday as a kid, listening to America’s Top 40, wearing out

thin lines of cassette tape, scraping grass off a lawn, in my room

prostrate with headphones, in every scenario, I was always alone.

So be easy on me if I exaggerate how gorgeous it feels to sing and

dance with you now. (93)

On the subject of poets and pop, the poet Reginald Shepherd writes in his 2008 essay collection Orpheus in the Bronx: “I suspect that for many contemporary poets popular music formed our first ideas of poetry.”[1] This is true enough for Brown, who notes: “My first experience of poetry in any form was pop music, which / taught me about poetry and magic, love and fucking” (21). In writing Top 40 as a conversation with the Top 40, Brown creates an expectation that his poems do some of what the songs do — that they occasion singing and dancing with the reader. We’re all in this together, in Brown’s poems, even when we’re allied in each being alone.

Top 40 is a procedure, or a few at once: forty sentences extending from each song in order to consider how pop music and making friends and keeping lists are all procedures. Brown cares, too, about how procedures usefully and gorgeously break down: “A transit strike can be breathtaking actually in how it redistributes / the possible,” he writes (58). Brown shifts among procedural unpackings of the songs and their lyrics, anecdotes of his daily routines and recent events, exchanges with people close to him, and accounts of what he’s reading (from Norse mythology to Kathy Acker to Rousseau). The book presents a time warp, where the poems catalogue their writing as it becomes October (“sweater weather”) and then winter as the book progresses, where the poems are in the present of the September 14th Top 40 and also in a shifting present where that Top 40 becomes a continuously receding past. The poems assemble into a kind of fragmentary completed portrait, a snapshot of the months around the writing of Top 40 in some of the ways a Top 40 is itself a biography of an American moment. Brown writes: “The structure of the Top 40 is not seismically safe, it cannot survive / unagitated longer than one week” (57): and yet the poems survive, even as they shift. The book is meant to become dated, but also to live on.

Brown thinks often in this book about lineage, as when he quotes from Alice Notley’s Culture of One: “‘The world isn’t a text to be deciphered, it is a new / creation though ancient — but what is antiquity to me’” (59).[2] And to Brown? Part of it is this: “When I look in the mirror I’m subject to a number of fantasies / about history and time travel” (69), which is the companion to the statement “The momentary eternal sounds like heaven to me” (71). These poems are a document of their moment, and a meditation on how antiquity and memory are carried on in the present as moments erode. They aspire to a momentary eternal, a trick of time where the present goes on forever, even as they map its impossibility. Through them, I learn that I prefer Top 40 with Brandon Brown to Top 40 with Ryan Seacrest as a way of keeping track of the present and its slippages.

Part of the moment of these poems is the aftermath in the Bay Area of the Occupy movement, and the November 2011 General Strike. In one reflection: “David often quotes Angela Davis, on the day of the General Strike in Oakland, saying ‘Our solidarities will be complex.’” (16) Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, often makes the argument that cultural production presages political action, and conversely, that cultural artifacts can demonstrate the political conditions of a given moment. In a 2004 interview with Oliver Wang, Chang notes, “Hip-hop shows how deeply the last thirty years of American history have been affected by the politics of abandonment.”[3] This makes me wonder about Brown’s procedural solidarities: list making, and returning to texts and ideas and people and language as ways of combating abandonment. These poems demonstrate that Brown feels the complexity of this moment’s solidarities everywhere, as he tests attachments to a catalogue of the features of his daily life.

These are poems that believe in coming together, but also demand the privacy of the self. Brown writes about listening to many of the songs obsessively, as he catalogues repeated actions: “Cigarettes, drinks, pills, chips, fucks, syllables, reps, hours on the / job, whatever it is, counting is addiction’s constant praxis.” (86)

Repetition and counting are an abandonment of the self to the logics of obsession, but also ways of saving the self from abandonment through returning again and again to its desires and needs. For as much as he believes in collectivity, he is at the center of these poems. “I guess I finally don’t know for sure what solidarity is” (115), he writes. The poems in Top 40 are a scout’s guide to how to celebrate living as a twinning of disavowal and adoration, as in his treatment of Charlie XCX’s I Love It: “I Love It hypothesizes that not caring can make love more not less / robust, that not caring can be the object of our most passionate / feelings” (48). Brown’s rapid parataxis can offer the idea that he doesn’t care, abandoning one idea for the next, but whatever not caring he does, it’s with an enormous heart, where not caring creates the opportunity for serious emotional investment, as he selects where and how seriously to direct his attention. Not caring is a defense in a framework of abandonment. Top 40 is a book with structure and a number of repeated themes, figures, and ideas, yet its locus and its drive are feelings: what feels good, what feels better, and where elective affinities create permission for tremendous waves of feeling, which are often private, but shared because we are told about them.

Brown writes, “I fucking love duets” (35), and that’s kind of what Top 40 is — a duet between Brown and the countdown, but also between Brown and the reader. Many of the tenderest moments are Brown alone with, or thinking about, or wishing for another person he names or doesn’t. In Top 40 repetition is the companion to change, or the catalyst for it, or the balm that makes it bearable, or its reflection, as Brown makes handsomely known: the music gets into all of us because we all have bodies and hearts, and so reading a book that’s a gorgeous mirror has to be a duet. I fucking love duets. Me in Brown, and Brown in me.

1. Reginald Shepherd, Orpheus in the Bronx: Essays on Identity, Politics, and the Freedom of Poetry (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008),17.

2. Alice Notley, Culture of One (New York: Penguin Books, 2011).

3. “A Can’t Stop Won’t Stop Q+A with Oliver Wang,” by Jeff Chang, cantstopwontstop.com, 2004.