Spelling for humanity

A review of 'Spells,' edited by Sarah Shin and Rebecca Tamás

Spells: 21st-Century Occult Poetry

Spells: 21st-Century Occult Poetry

Language work is a making and remaking of the world around us, a casting of spells: “To be a witch, then, is to know words.”[1] Spells, an anthology edited by Sarah Shin and Rebecca Tamás, attempts to show the magical side of poetry and “the moment before the word, when everything inside you is broken open” (ix). The purpose of Spells is made clear in many ways, from the chant-like lyrical prose introduction “The Broken Open” by So Mayer to the subtitle: “21st-Century Occult Poetry.” This is a book of poetry that does magic, that believes in the magic of word-casting and spell-ing. Spells introduces a variety of ways to spell in poems from a diverse cast of poets who echo the ideas of precursors like Ursula K. LeGuin: by naming something, magic is done and change is created.

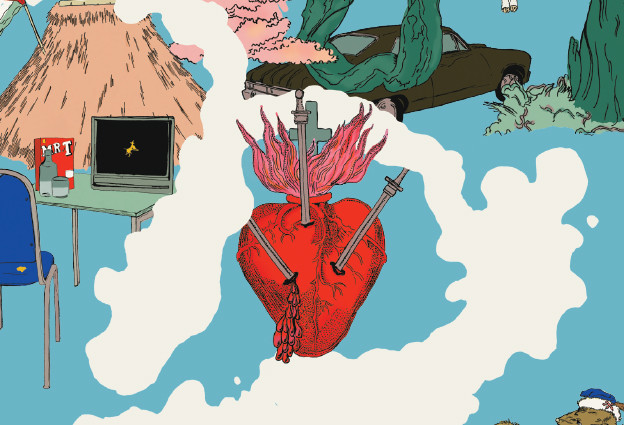

Publishing “at the intersection of technology, myth-making and magic,” Ignota Books designed a cover cut-out “portal” to reveal the image of a bleeding heart as well as, nested inside that, another portal. These nested portals suggest movement as well as conjuring “portals” to other ways of thinking and using language.The book makes a plain purpose for poetry, both excerpted on the back cover and in the introduction: “poetry is spelling,” and words “influence the universe.” Spelling and spell-ing act as both pun and infinitive, “to spell,” inscribing the magic of writing as creation. Spells is an anthology for wordsmiths, tying the voice, language, and ritual to spelling and enacting “your true identity” (xvii).

The poems included range from conversational to experimental to traditional; thematically, the anthology includes trauma, feminism, and ecology, allowing for typical notions of “witchiness” as well as contradiction and redefinition, respelling, and considering all ways of productive language use. Spells can produce new ideas and definitions that influence ways of being in the world, undoing oppression: “witchcraft — like the violence it opposes — works by repetition, by the looping and looping and looping of a thread, by the network of words” and not by one rote definition (xiv). Because of the openness of this logic, by which all language use and all spellings are “witchy,” Spells also inscribes the impossibility of its own failure. All spells are considered here, and there is not a single position taken on what constitutes “right” spell-casting because of the mix of traditional imagery like crystals alongside complex feminist polemic.

On one hand, using crystals and the elements to create a poem like Jen Calleja’s “The Gift” or Ariana Reines’s twenty-page “Thursday” doesn’t expand notions of witchery in writing but limits it to the traditional and in many cases stereotypical; on the other hand, these depictions validate originary notions of witchcraft in language-making and carve open even more space for wordsmiths. Calleja’s “The Gift,” for instance, claims an increase of potency “by snacking on”

creamed opals

topped with a trickle of gems: shards of

citrine, aventurine, tourmaline, almandine

negating the produce of the cow, the goat, the sheep (10)

In the naming of crystals, Calleja may be read as succumbing to the new age stereotype of witchery and the materials of healing, and yet the naming of these specific crystals — citrine, aventurine, tourmaline, almandine — is also a language act, a spell cast through denotation. It is both stereotype and the appropriation of that stereotype that make spells like Calleja’s potent — or potential.

Poems like Rachael Allen’s “Banshee,” which reads as a witch’s revenge poem (“tonight I laugh walking / towards his dark house” [3]), and A.K. Blakemore’s “golem” (“go down to the river and make a man with your bare beautiful / hands and knowledge of sacred geometry” [8]) can fall a bit flat in their traditionally “occult” notions, and one can’t help but notice that Reines’s poem in particular takes up an enormous percentage of the 160 pages of the anthology. Still, readers can appreciate Khairani Barokka’s astrological references to “Venus retrograde, in Aries, twelfth house” (5) and the power of blood in Caspar Heinemann’s “FULL MOON LEECH PARTY” as nods to one practical aspect of Spells: doing language means, often, doing ritual and incorporating tradition.

By having poems that adhere to the traditions of the “occult” alongside those that break these boundaries, Spells allows a comfortable reading back and forth from the surprising to the understood. Reines in particular tells that “the god in my mouth” both names things and expels things and can draw a ritual symbol or work a metaphor, naming through repetition, reiteration, etymology, and other denotations (83). It is well worth noting that Reines’s “Thursday” constitutes a pivotal sequence in her recent A Sand Book that carries over from her longer collection to Spells both the power of ritual and the gravity of incantation.[2] Reines’s work, inspired by the traditions associated with the occult as much as by contemporary culture and technology, is a melding of talismanic signatures like the symbol that opens “Thursday” and reference culture:

Thurgood Marshall

Uma Thurman

Thelma Golden

Thor

Sir Thomas More

Thor

Heavy One

Sky Man

Thor’s day

Thor (81)

The success of Reines’s piece in Spells, as long as it may be, hinges on the reader’s acceptance of the poem as both spell or talisman and cultural reference. The belonging of each element of the incantatory beginning quoted here is dictated largely by the inclusion of the “th” vocable but also incorporates rhyme and alliteration, as evidenced by “Thor/More” and the “m” in “Thelma/Thurman.” It is when reading the sequence aloud that the spell-casting capacity of “Thursday” is discovered; in this reading, the poem is both speaking to tradition and rubbing against it with modernity.

On the other side of the circle sit the poems that don’t strike a reader as “traditional” or typical witchcraft but play with the idea of witching and language — some seeming to counter the idea, like Dorothea Lasky’s former “night witch” who “used to sing and sing and it was for nobody” (50). Poems that indicate their intentionality with their titles like Bhanu Kapil’s “Spell to Reverse a Line” declare that they are spells, and so they are. In writing these words, Kapil enables magic to permeate the act of reading:

You can travel.

To these places.

In your dreams.

In your extreme way of making art.

In what it is to be with others.

In the way that you are with others.

Here.

Forever.

Now. (44)

Kapil’s spell names trauma, using end-stops as declarations and doings — much like Allen Ginsberg’s famous “Wichita Vortex Sutra” declares the end of the war.[3] As the introduction to Spells dictates: “What a spell creates, as you speak it, is you: a sense of your power to create. A spell spells you” (xix).

We can spell “thinking of self-love,” as in Kaveh Akbar’s “Prayer” (1), or thinking of cauldrons and runes. Perhaps more lovingly still, we can spell thinking of contemporary resistance and inclusion. Magic is a form of protest, spelling a type of social justice through naming and reclaiming. The editors of Spells maintain a very clear focus on including diverse voices and many feminist embodiments of spelling throughout. Some of it is violent, from Rebecca Perry’s “impaled men and boys” (68) to #MeToo’s yes “all men” echoed by Nisha Ramayya (75). But Spells is also interested in a “pluralistic magical language” (xi) that reflects a semiotic space, the preverbal and maternal communication “of what eludes speech” (per Nia Davies, 22) and the symbolic order that Kristeva’s jouissance embodies in Powers of Horror.[4] Spelling can move language beyond mere symbolism into embodiment and action, can “destroy the whole world the great / spreadsheet” in order to build it again fresh (79).

Anthologizing strips poems of one container to give them another; in this anthology, each becomes a magical byte of just one person’s practice of spelling. Well-known names stand out of the anthology’s list of contributors, but all are given an even alphabetical order in the book. Ideas of success in a traditional or radical magical vision of language aside, the book’s intention to present multiple perspectives without biasing toward tradition or type is clear. “Recording history is, after all, itself a spell,” a reordering and narrativizing of events, giving them symbolic meaning (xiv). In this way, Spells urges the reader to care for these and for all words, to spell with self-love and world-love, to, as Rebecca May Johnson has it, “purge the desire to write like a man” (33) and write maternally instead. The portal in the cover is a portal to look out at the world through, like a spyglass of perspectives on practical magic and practical poetry — Erica Scourti’s “something / to hold / a protective shell” (114) to come away with. Spelling for humanity, for love, becomes the maternal language of the trees, as in Emily Berry’s “Canopy,” which incants:

And the trees shook everything off until they were bare and clean. They held onto the ground with their long feet and leant into the gale and back again.

They flung us down and flailed above us with their visions and their pale tree light.

I think they were telling us to survive. (7)

1. Sarah Shin and Rebecca Tamás, eds., Spells: 21st-Century Occult Poetry (London: Ignota, 2018), x.

2. Ariana Reines, A Sand Book (Portland, OR: Tin House Books, 2019).

3. Allen Ginsberg, Planet News (San Francisco: City Lights, 1968).

4. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).