Tania De Rozario: On the monstrous feminine

"Does one named woman communicating with another named woman still count as a positive on the Bechdel test if one woman is not actually human?" - Tania De Rozario

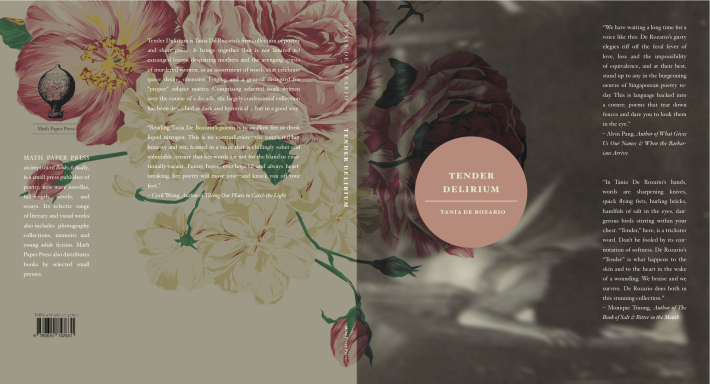

Tania De Rozario is an artist, writer and curator interested in issues of gender and sexuality, representations of women in Horror, and art as activism. Her practice hovers on the intersections between text and image, and her work has been showcased in London, Spain, Amsterdam, Singapore, New York and San Francisco. Tania is the author of Tender Delirium (Math Paper Press | 2013), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Singapore Literature Prize, the winner of the 2011 NAC-SPH Golden Point Award for English Poetry, and recipient of the NAC Arts Creation Fund for her literary memoir, And The Walls Come Crumbling Down. She is also runs EtiquetteSG, a multidisciplinary platform focused on developing and showcasing art, writing, film and music made by women. As an Associate Artist with The Substation, Singapore's oldest independent art centre, her work has included embarking on Making Trouble, a research project documenting links between Visual Art and activism in post-2000 Singapore. Tania's poetry and fiction have been published in numerous journals and anthologies. She has also written extensively about art.and has undertaken residencies at NUS, (Singapore), Hedgebrook (USA), Sangam House (India), The Unifiedfield (Spain) and Toji Cultural Centre (South Korea).

Divya:Tania, last week I heard you perform at SPEAK— a cornerstone of Singapore’s Spoken Word scene. And, as with much of spoken word work, the focus was on the personal tuned to the key of the political. And I appreciated, in particular, the poets’ insistence on exhuming the bodies of the denied/fetishized/advertised/ “on-sale”/pillaged female identities and cultures. Gender made trouble on that stage and it was really instructive to witness, especially as someone who is still learning about the Singapore poetry landscape. Of your set, the particular poem that I found myself investing in was “Onnen”, a poem from your book Tender Delirium (Math Paper Press, 2014). “Onnen” is a Japanese word that refers to an affective haunting— an emotion that lingers after death— a kind of stain. And the poem (which we’ll feature here) attends to three iconic fictional women of Japanese and Thai horror cinema: Kayako Saeki (The Grudge/Ju-on); Sadako Yamamura (Ring Trilogy/Ringu); Natre (Shutter). I’ll place the poem here:

怨念 (Onnen) Listen to De Rozario read this poem at PennSound

For the dead women in Ju-On, Ringu and Shutter.

1. Kayako

She is prolific, this one, keeps it

in the family; works with her son

who screams for her, mouth ebony

black, the sound of a thousand cats

strangled in his throat. Killed

by the man of the house, bludgeoned,

and screaming, hair matted with blood

as they entered into death with rage

so thick it seeped into every crevice

of that house; she will take the world

with her. Suspended from the ceiling,

she will drop her hair like Rapunzel,

lynch you with her locks while the boy

pushes your corpse back-and-forth

like a tire swing. As she descends

from the stairs, you will hear her

voice, moaning in a slow choke

as she crawls on all-fours, thinking

if we have to live here for the rest

of forever, so will you. So will you.

2. Sadako

An urban legend, though she lived

by the sea with her parents: Mother,

gifted with second sight, daughter with

an untamed fury that can upturn furniture

with a single glance. That is how she kills

witnesses who chance upon the video

of her life; random static, the dread

of knowing that it is your turn now

to be singled out for a week of waiting

for death. It is arbitrary, who dies,

who doesn’t. Some stumble upon

the tape in old hotels, others get copies

from friends. All their bodies turn up

with faces frozen into primal screams,

eyes wide with knowledge, understanding

everything except for how she too

awaited death, tried to claw

her way out of the dark, wet tomb

her father tossed her into: She

still learns from his lack of mercy.3. Natre

They ganged up on her. All five

at once; the ring-leader pounced,

having his way. Done, he got off,

insisted his friend take her

picture “to make sure that she

doesn’t blab”. She told no one, and

instead, jumping to her death, kept

two secrets: The first - she had

been raped. The second - her lover

had been the one to shoot her

with the camera she’d bought for him

on his birthday. So now she shows up

in developing photos, slinks her way

about his darkroom, fills his friends

with so much fear, they too jump

to their own demise. Except

for him: For him, she will stay,

arms about his neck as she sits

upon his shoulders like the weight

of guilt: This is how she loves him.

The many living rooms of my life in Baltimore, Buffalo, and Singapore are haunted by these women, respectively. I’ve seen them crawl off the wall, out of the well, down the ceiling; I’ve watched them taking over my own space while also avenging forms of gynofocal violence that they embody, as victims. They stain and contextualize really intimate spaces in my life. In this way, they both horrify and comfort me— they wind themselves around and around that dichotomy of the maternal-demonic, as players in the cultural horror of the feminine.

So, I’d like to start by talking about scary movies because they waltz between terror and horror (the dance of the sublime) and because they are more honest about the gender relations and the political place of the ‘feminine’ than any other genre of cinema. And I think these are close to your own heart too—so let’s begin there.

Tania: I love how you describe the way these women have shared space with you. I feel the exact same way! I’ve always been a fan of horror. It might be because it was “forbidden” during my childhood. My mother was very strict about horror films and books; I was never allowed to watch or read any. She was convinced, regardless of content, that they were filled with the devil and that the devil would enter my life if I engaged with him. But then again, she was also convinced that the devil could enter our lives if we practiced anything from yoga to taekwondo.

The minute I had access to cinemas and libraries, I started watching and reading all sorts of horror—all of which interested me but none of which scared me. In my teens, I absorbed a lot of American horror – A Nightmare on Elm Street, Child’s Play, demonic possession, haunted houses – stuff that could be easily acquired from video stores. When I dropped out of Junior College and went to art school, I paid for my first year there ghostwriting ghost stories for a crappy publishing house. And in my second year of study, I took a Monstrosities class, in which I was introduced to the idea of the Monstrous Feminine – something I took to straight away. It was around this period of time that I watched Ringu in the cinema.

Divya: And this is where one of the protagonists of your poem “Onnen” emerges: Sadako Yamamura!

Tania: Yes, Ringu. For the first time ever, I was terrified. It did not help that it was a late-night show and that I had not seen any of the film trailers. I was convinced that if I watched the film again, I would gain some objectivity and feel less afraid. So I watched it in the cinema a second time. And a third. What a stupid idea. By then, every other thing in my house scared me – the television, cameras, videotapes, videotape players, my morning hair in my reflection. The fear lingered for weeks.

But despite the overwhelming terror, the irrationality of my fear was also something I found fascinating, simply because nothing on screen had ever scared me to this extent. There was something immensely “foreign” about Ringu that added to how disconcerting the experience was. Yes, there were the aesthetic aspects of the film that were new to me – the sparse soundtrack, the lack of overt-explanation common in Hollywood horror, the minimal use of camera tricks - but I think what really scared me was the randomness and the inevitability. If you happened to watch that videotape, you would die. It did not matter who you were; you would die and you would be found with your face stretched into a scream of terror with no logical explanation regarding the cause of death.

Divya: And it is the shift in the moral paradigm here that is particular to Ringu and to Sadako’s “feminine monstrous” role here…

Tania: Sadako’s revenge did not discern and it did not discriminate. Her rage did not qualify or quantify- it just was. And worst of all, it transcended any sort of good-evil binary that tended to dominate Western horror. There was no possible redemption for anyone who stumbled upon Sadako’s reality: either you died in terror, or you made sure that someone else died by passing a copy of the tape to someone else. Everyone in this reality – including the film’s protagonist, is forced to be either a victim or villain, except for Sadako, who is both.

Since then, watching many Asian (particularly Japanese and Korean) horror films, I’ve realized that there is a certain archetype that is always reiterated when it comes to female ghosts, and that their horror is rooted to their identity as female, in the tension between agency and oppression. On one hand, the typical female ghost is a fierce, autonomous character who seeks justice on her own terms; on another, this agency is only granted in death. And, despite the fact that she is almost always a victim of murder, or sexual assault, or both, she is always portrayed as a monster. That’s a lot of misogyny and feminist possibility to mix together into a single bowl of terror and thought. Also, the protagonist she is often connected to or communicating with over the course of the film, tends to be a woman. Does one named woman communicating with another named woman still count as a positive on the Bechdel test if one woman is not actually human?

Divya: What a great question! The problem here is, of course, that the line between the human and the monstrous is a gendered one— that is where the cut falls and the parts split, as it were. The species spectrum is also a gender spectrum and vice versa, within the logic of horror types.

Tania: Of course, the relation between gender and horror is neither new, nor isolated to Asian portrayals. Even with classic Hollywood archetypes -The Vampire, The Werewolf, The Zombie, The Mummy – there is no character whose horror is so rooted in gender as The Witch, which, if you think about it, is the only character in that canon who is human. While fear of all the other villains is cultivated through a general defiance of the laws of Life vs. Death, and Human vs. Animal, fear of The Witch seems to be derived precisely from her perversion of traditional femininity: She is a failed sex object - by normative standards; she is considered "old" and "ugly. She is not a worthy homemaker or wife - in fact, she uses tools of domesticity for evil, riding a broomstick and cooking up potions over her stove. She is not a worthy mother - she eats children (hahaha). And of course extensions and variations of how traditional roles of woman/girl have been destroyed in order to create monstrosity is evident in classics such as the Alien trilogy, The Exorcist (which was actually based on the story Roland Doe, a boy and not a girl) and every other femme fatale movie that has ever been made.

Divya: What does “horror” as a genre or as a response to the feminine make possible for you, your poetry?

Tania: I’m not sure what horror as a genre makes possible for my poetry, except that my third book is in the making, and that there is an entire section dedicated to ghosts. And of course my sustained interest has allowed me to meet other individuals with overlapping interests and subsequently organize events such as A Certain Sort of Hunger and Death Wears a Dress. I’m certainly no academic authority on Horror, but what I can say is that because Horror plays on the things we fear, its poetic quality lies in its potential to tell us more about the monsters inside ourselves, rather than those outside. I think this is very evident in the victim/villain paradox in Ringu, very evident in many novels by Stephen King, of whom I am a big fan. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that in the world of film, Horror franchises tend to be the only ones marked by largely by their villains and not their heroes. From Freddy to Sadako to Chucky to Bates to Leatherface to the mastermind in Saw. The constant in all these franchises are the monsters, whose stories get developed over the course of the franchise, while the “protagonists” are interchangeable, of secondary importance, with exceptions such as the Alien franchise, protagonists rarely survive an entire series. It is the monsters we are interested in – they are the real protagonists. Somehow, we’re on their side.

I think good horror stories tell us the truths of the horrors individuals and societies are capable of. Women like Sadako, Kayako, Natre – they exist. All you need to do is look at statistics pertaining to the violence against women, perpetrated by people they know, people who are supposed to be loved ones, supposed to be family. And in all honesty, we all exist and are part of a culture that has allowed and contributed to this violence. So why shouldn’t these women be crawling into all our lives and into our homes to remind us of that?

Listen to De Rozario read 怨念 (Onnen) from Tender Delirium at PennSound

DISCOURSES ON LOCALITY: Singapore