Shots fired

Exit Theater

Exit Theater

If in Act 1 you have a pistol hanging from the wall, then it must fire in the last act. — Anton Chekhov[1]

What if Chekhov’s gun were a poem? We have Emily Dickinson’s “life,” for starters, standing as a loaded gun, charged, as in the sense of the French charger, purposeful and pregnant, but whose meaning comes in its execution. Dickinson’s gun uses its life to lose it. Or maybe Wilfred Owen’s military weapons, artillery and gas, a modernism of ironic death and slow, lingering decline. (Songs of war, of course, are nearly as old as poetry itself; suffice it to say that Achilles’s shield is not Chekhov’s brace of pistols.) Where Owen wanted to separate the historical lies of poetry from the reality of weaponized modernity, Amiri Baraka asserted Black art’s right to bear arms: “we want ‘poems that kill.’ / Assassin poems, Poems that shoot / guns.” Another tradition turns our attention to the victims of gun violence, whether in Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony, Gwendolyn Brooks’s “The Boy Died in My Alley,”or, more recently, Maggie Nelson’s poetry of bullet holes, spilling the light of the mind in Jane: A Murder.

Despite these examples, the Poetry Foundation website doesn’t offer users the chance to explore “Poems about guns.” Perhaps this has something to do with the difference between gun as story and gun as poem. Chekhov’s principle, after all, was proposed as an instance of narrative economy — the guns must go off to maximize causal continuity and minimize narrative waste. And gun as theater: the pistol on the wall entangles diegesis and mimesis, where objects both show and tell. The scene is also the plot; the props ultimately determine action. Dramatic narrative may be the aesthetic purview of the gun, just as the gun, in turn, injects drama into US history. Our political theater is a repertoire of explosions, always expected (the gun must go off), always surprising (we don’t know precisely when), always, perversely, satisfying (we always knew this would happen).

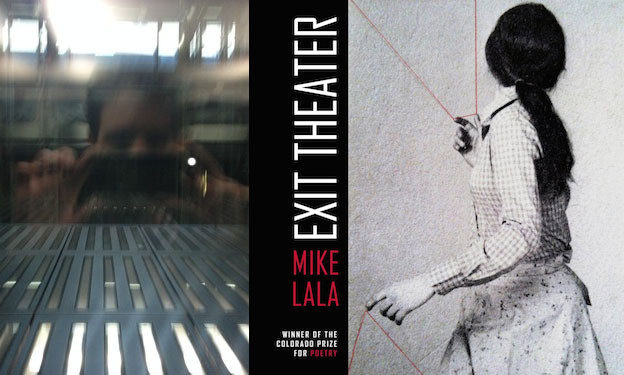

Causality and aesthetic efficiency, staged expectations and reality effects, the chargé that is also a discharge, all are affects in the time of violence, time not as epoch but as duration, as the continuity of lived experience. It is this phenomenological, durational time of violence that measures Mike Lala’s Exit Theater, winner of the 2016 Colorado Prize for Poetry. Lala’s book choreographs a range of poetic and discursive forms to demonstrate the continually evolving barrage of Chekhovian guns in contemporary life, the folds of their inevitability and the complexities of our cathartic identifications. Simultaneously elegy and poetic sequence, theater and documentary, ekphrastic and translational, the book’s continually self-disrupting and adapting formal range unsettles Chekhov’s economy. These interlocking formal movements suggest the poem not as narrative but as field, a texture of destructive effects and affects, from the rapid immediacy of actual guns (domestic, military) to the longer historical arc of ecological catastrophe that Rob Nixon has called “slow violence.”[2] Lala’s book manifests these cumulative senses of our time, the dull, buzzing inescapable ache that arises when the weapons have come off the stage and constitute the real, everywhere and nowhere.

In this world, every entry is already an exit, and the book’s prefatory poem, “Say Goodbye to the Shores,” invokes that taking leave. A rendition of “Catullus 101,” the poem addresses objects — rudders, microphones, the poem itself — as if the book were commencing a voyage to nowhere: “Little mirror, / here’s to you: A drink. The passage. Goodbye.”[3] We are invited into a farewell, a passage as journey, as death, as the losses of time. With this opening poem, the volume’s title also comes into focus, as either imperative — to exit the theater (whether of life or illusion), or as self-descriptive — a theater of exiting, the staging of departure in its inevitable, unpredictable forms. We are reminded that the elegy is both genre and occasion, traditional and personal. Loss is both a reality and a role.

The remainder of the book, divided into three sections, expands the opening poem’s elegiac mourning and praise. The first section, “Say To the Shores,” also begins with an ending, opening with “Suite w/ a View for the Ends of Our Days (Three Plinths),” a city poem built on three interlocking structures: a walk down a New York street, a column of notes documenting impending disaster, and a list of URLs as supporting evidence for these notes. The result is an ontological uncertainty, a refusal to ground experience in either the subject or the smartphone, but also a brief microcosm of interconnectedness, a sign that, off stage, the guns are loaded. We may experience the rush of sensoria — “fake silks, blown glass, bulwark steel edge of sidewalk, taxi cars’ yellow aluminum up 6th” — but these experiences are grounded in historical and ecological forces, some benign, singular, others disastrous: “Soon (& finally) the grain will fail to pollinate” (3). The notes direct us to the right-hand column, where we are given a history of the steel-faced curbing in New York and the reminder that “Global warming trends will soon (and have already started to) upset the global balance and production of food” (3). The poem formalizes the fractured (and distracted) subject of the present, for whom the experience of the city’s pleasure is tempered by the realization of the ecological gun hanging on the wall. As the poem continues, selfies are taken, lipstick is applied, jeans are purchased, while, on other shores, the plankton destructively blooms, the fish are poisoned by mercury, and a polar bear, displaced by melting ice, devours its own offspring. The exits are multiple.

The confusion of ends and beginnings, of event as singularity and connection as continuity, is most evident in the book’s second section, “In the Gun Cabinet,” a porous, interlocking sequence of poems whose individual endings and beginnings are blurred, discontinuous, without marked beginning or end, each poem bleeding into the next. This gun cabinet is a family affair, populated by “brother,” “father,” and perhaps dominated by “mother,” who is both a spectral presence, a memory, and a body “in wake” (31). Fragmented, ethereal, sexual, unconscious, the family in these poems is both weapon and sanctuary, violence and order. The brother’s finger bleeds, pierced by a fragment of wood; the father’s gun is dropped as “it pitched and went off” (27). Accidents accumulate into a history of loss that constitutes the subject as difference: “There is a violence here / that folds you,” while “the bodies you inhabit through your life / stand up like guns inside the doors” (29, 36). The tone fluctuates between confession and abstraction, family as autobiography and family as structure. In both forms, the gun cabinet remains, “hissing in the background” (35), an inescapable drone that disappears through its constant presence. The poems are less therapy or incantation than they are a record of coping, of living with the folding of violence that touches even the most intimate relationships. Or, family is like a vulnerability to loss that is always politicized, militarized, loaded. From Archilochus: “in the hospitality / of war / We left them their dead / as a gift” (43). The domestic drama, in other words, couples to the theater of war, as the gun cabinet is also a stage. “Interview,” the final poem of “In the Gun Cabinet,” is presented as a play in which “I” and “M” seem to be indirectly analyzing the poems we have just read, stumbling toward an articulation that they cannot achieve.

“Interview” escorts us to “Exit Theater,” the book’s final section, which dwells on the ironic “hospitality of war.” In this section, Shakespeare becomes a dominant figure, and the bodies stack up. “Slaying is the word,” Brutus reminds us. “It is a deed in fashion” (63). But, in the fashion of our times, that deed is also image, televisual, transmediated, informational, the subject of surveillance and data. Two of the final poems in the book turn to US military engagement abroad as an elegy to our collective appetite for the sensational fictions of war. “Twenty-Four Exits (A Closet Drama)” presents the spectacle of real violence in imagined theaters. An audience watches snippets of film and language drawn from targeted assassinations on an international scale, ending with the US drone strikes that killed Anwar al-Awlaki, his sixteen-year-old son Abdulrahman, and Samir Kahn — all American citizens. State violence, like terrorism, becomes both text and body, a language both secret and public, implicating all. In “Self_Interrogation (Kill Team),” the murder of Afghan civilians by US Army soldiers becomes “an image,” “A likeness of ourselves,” requiring self-questioning and self-doubt: “And through language, speaking, dialogue(??) the code, breaking like ‘accidental discharge’ on the other side of a wall” (79, 74). Like the audience in a theater, we cannot extricate ourselves from the moment when the weapons go off. Perhaps this theater has no exit; the discharge is never, finally, an accident.

Through its movements from the elegy to Afghanistan by way of the gun cabinet, Lala’s book ultimately stages a new question, perhaps an inevitable question, for aesthetic work in these times of violence: what happens when Chekhov’s gun becomes a drone, a melting ice cap, a toxic algae bloom? Causality, expectation, inevitability, narrative and poetic pleasure, all must be recast when confronted with the multiple time scales and emergent agencies, whether human or object, executive order or weaponized technology, that constitute the present. For, as Exit Theater reminds us, the ordinance is spreading.

1. Ilia Gurliand qtd. in Donald Rayfield, Anton Chekov: A Life (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1997), 203.

2. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

3. Mike Lala, Exit Theater (Fort Collins, CO: Center for Literary Publishing, 2016), vii.