Twenty-six items from Special Collections (r)

Exhibit ‘R’: Russian. (Anton Chekhov, 58 items from his notebooks)

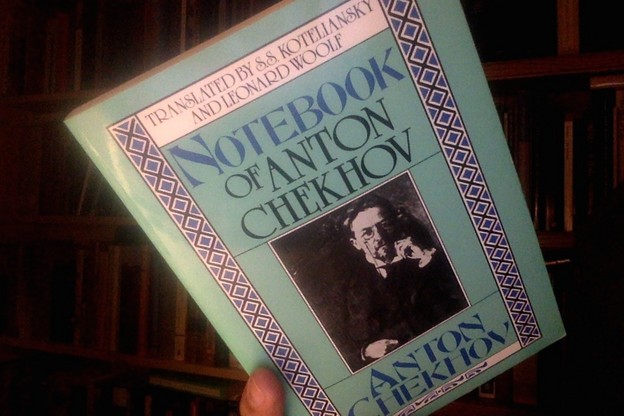

Bibliography: Notebook of Anton Chekhov, translated by S.S. Koteliansky and Leonard Woolf (Ecco, 1987). Originally published by B.W. Huebsch, Inc., 1921.

Comment: I am constitutionally opposed to the application of the statement You either have it or you don't to any situation whatsoever. My abiding intuition is that that sentence is mainly a means by which eminent persons discourage beginners.

Worse, since every beginner faced with that evil idea simply must admit that the available evidence is not favorable to their candidacy, only the strutting asses among them—whose self approval requires no outward manifestation of merit—are able to proceed. Whoever is modest enough to admit she was not born a Mozart is urged to hang it up already.

But is it not possible the evil sentence is true, for all that? I am forty-seven years old; I work with high school students. I have to admit: It's medically impossible for me to imagine four-fifths of ’em ever writing a poem, making a drawing, constructing a narrative, or coining an aphorism. If they pick up a little booklet and perceive it contains art writing of any description, they put it back right away—in the same way I would put back a colorful ad for a monster truck show. Got nothing to do with me.

I don't say they were born this way. I'm saying if you make it to sixteen without Factor X, I'm willing to bet twenty bucks you'll go to your grave without it. My only insight is that Factor X is not talent.

I am going to propose that "Factor X" is simply a lust for expressive speech. That is the "it" in You either got it or you don't. If you have that, you have the rock on which a house can be built. If not, not.

What does any of this have to do with Chekhov. Only this. When teachers wish to nurture expressiveness in young people, they (the teachers) should make a point of sharing with the kiddeos selections from writers' notebooks. These show the beginner that a master's seedlings don't look that different from her own. Then teach the beginner to keep such a notebook! Excellent phrases overheard, witty lists, ideas for stories.... The front side of one sheet of paper might be enough to undo the damage of having heard that you either got it or you don't.

from The Notebooks of Anton Chekhov

A scholar, without talent, a blockhead, worked for twenty-four years and produced nothing good, gave the world only scholars as untalented and as narrow-minded as himself. At night he secretly bound books—that was his true vocation: in that he was an artist and felt the joy of it. There came to him a bookbinder, who loved learning and studied secretly at night.

Do you want to eat?

No, on the contrary.

A schoolboy treats a lady to dinner in a restaurant. He has only one rouble, twenty kopecks. The bill comes to four roubles thirty kopecks. He has no money and begins to cry. The proprietor boxes his ears. He was talking to the lady about Abyssinia.

Two wives: one in Petersburg, the other in Kertch. Constant rows, threats, telegrams. They nearly reduce him to suicide. At last he finds a way: he settles them both in the same house. They are perplexed, petrified; they grow silent and quiet down.

Z. goes on Sundays to the Sukharevka (a market-place in Moscow) to look for books; he finds a book, written by his father, with the inscription: “To my darling Nadya from the author.”

These red-faced young and old women are so healthy that steam seems to exhale from them.

First class sleeping car. Passengers numbers 6, 7, 8 and 9. They discuss daughters-in-law. Simple people suffer from mothers-in-law, intellectuals from daughters-in-law.

"My elder son’s wife is educated, arranges Sunday schools and libraries, but she is tactless, cruel, capricious, and physically revolting. At dinner she will suddenly go off into sham hysterics because of some article in the newspaper. An affected thing.” Another daughter-in-law: “In society she behaves passably, but at home she is a dolt, smokes, is miserly, and when she drinks tea, she keeps the sugar between her lips and teeth and speaks at the same time.”

In the servants’ quarters Roman, a more or less dissolute peasant, thinks it his duty to look after the morals of the women servants.

An official, who wore the portrait of the Governor’s wife, lent money on interest; he secretly becomes rich. The late Governor’s wife, whose portrait he has worn for fourteen years, now lives in a suburb, a poor widow; her son gets into trouble and she needs 4,000 roubles. She goes to the official, and he listens to her with a bored look and says: “I can’t do anything for you, my lady.”

Prostitutes in Monte Carlo, the whole tone is prostitutional; the palm trees, it seems, are prostitutes, and the chickens are prostitutes.

Really decent people are only to be found amongst men who have definite, either conservative or radical, convictions; so-called moderate men are much inclined to rewards, commissions, orders, promotions.

I visit a friend, find him at supper; there are many guests. It is very gay; I am glad to chatter with the women and drink wine. A wonderfully pleasant mood. Suddenly up gets N. with an air of importance, as though he were a public prosecutor and makes a speech in my honor. “The magician of words . . . ideals . . . in our time when ideals grow dim . . . you are sowing wisdom, undying things . . . ” I feel as if I had had a cover over me and that now the cover had been taken off and some one was aiming a pistol at me.

A large factory. The young employer plays the superior to all and is rude to the employees who have University degrees. Only the gardener, a German, has the courage to be offended: “How dare you, gold bag?”

At twenty she loved Z., at twenty-four she married N. not because she loved him, but because she thought him a good, wise, ideal man. The couple lived happily; every one envies them, and indeed their life passes smoothly and placidly; she is satisfied, and, when people discuss love, she says that for family life not love nor passion is wanted, but affection. But once the music played suddenly, and, inside her heart, everything broke up like ice in spring: she remembered Z. and her love for him, and she thought with despair that her life was ruined, spoilt for ever, and that she was unhappy. Then it happened to her with the New Year greetings; when people wished her “New Happiness,” she indeed longed for new happiness.

N., a dramatic critic, has a mistress X., an actress. Her benefit night. The play is rotten, the acting poor, but N. has to praise. He writes briefly: “The play and the leading actress had an enormous success. Particulars to-morrow.” As he wrote the last two words, he gave a sigh of relief. Next day he goes to X.; she opens the door, allows him to kiss and embrace her, and in a cutting tone says: “Particulars to-morrow.”

In Kislovodsk or some other watering-place Z. picked up a girl of twenty-two; she was poor, straightforward, and he took pity on her and, in addition to her fee, he left twenty-five roubles on the chest of drawers; he left her room with the feeling of a man who has done a good deed. The next time he visited her, he noticed an expensive ash-tray and a man’s fur cap, bought out of his twenty-five roubles—the girl again starving, her cheeks hollow.

N. and Z. are intimate friends, but when they meet in society, they at once make fun of one another—out of shyness.

Mitya and Katya were told that their papa blasted rocks in the quarry. They wanted to blow up their cross grandpa, so they took a pound of powder from their father’s room, put it in a bottle, inserted a wick, and place it under their grandfather’s chair, when he was dozing after dinner; but soldiers marched by with the band playing—and this was the only thing that prevented them from carrying out their plan.

A radical lady, who crosses herself at night, is secretly full of prejudice and superstition, hears that in order to be happy one should boil a black cat by night. She steals a cat and tries to boil it.

N. rings at the door of an actress; he is nervous, his heart beats, at the critical moment he gets into a panic and runs away; the maid opens the door and sees nobody. He returns, rings again—but has not the courage to go in. In the end the porter comes out and gives him a thrashing.

The most intolerable people are provincial celebrities.

“I have not read Herbert Spencer. Tell me his subjects. What does he write about?” “I want to paint a panel for the Paris exhibition. Suggest a subject.” (A wearisome lady.)

A girl, flirting, chatters: “All are afraid of me . . . men, and the wind . . . ah, leave me alone! I shall never marry.” And at home poverty, her father a regular drunkard. And if people could see how she and her mother work, how she screens her father, they would feel the deepest respect for her and would wonder why she is so ashamed of poverty and work, and is not ashamed of the chatter.

A dealer in cider puts labels on his bottles with a crown printed on them. It irritates and vexes X. who torments himself with the idea that a mere trader is usurping the crown. X. complains to the authorities, worries every one, seeks redress and so on; he dies from irritation and worry.

A little girl with rapture about her aunt: “She is very beautiful, as beautiful as our dog!”

They undressed the corpse, but had no time to take the gloves off; a corpse in gloves.

N. forty years old married a girl seventeen. The first night, when they returned to his mining village, she went to bed and suddenly burst into tears, because she did not love him. He is a good soul, is overwhelmed with distress, and goes off to sleep in his little working room.

Son: “To-day I believe is Thursday.”

Mother: (not having heard) “What?”

Son: (angrily) “Thursday!” (quietly) “I ought to take a bath.”

Mother: “What?”

Son: (angry and offended) “Bath!”

A very intellectual man all his life tells lies about hypnotism, spiritualism—and people believe him; yet he is quite a nice man.

N., the manager of a factory, rich, with a wife and children, happy, has written “An investigation into the mineral spring at X.” He was much praised for it and was invited to join the staff of a newspaper; he gave up his post, went to Petersburg, divorced his wife, spent his money—and went to the dogs.

Z: “As you are going to town, post my letter in the letter-box.”

N: (alarmed) “Where? I don’t know where the letter-box is.”

Z: “Will you also call at the chemist’s and get me some naphthaline?”

N: (alarmed) “I’ll forget the naphthaline, I’ll forget.”

A conversation at a conference of doctors. First doctor: “All diseases can be cured by salt.” Second doctor, military: “Every disease can be cured by prescribing no salt.” The first points to his wife, the second to his daughter.

A man, married to an actress, during a performance of a play in which his wife was acting, sat in a box, with beaming face, and from time to time got up and bowed to the audience.

When N. married her husband, he was junior Public Prosecutor; he became judge of the High Court and then judge of the Court of Appeals; he is an average uninteresting man. N. loves her husband very much. She loves him to the grave, writes him meek and touching letters when she hears of his unfaithfulness, and dies with a touching expression of love on her lips. Evidently she loved, not her husband, but some one else, superior, beautiful, non-existent, and she lavished that love upon her husband. And after her death footsteps could be heard in her house.

A theatrical manager, lying in bed, read a new play. He read three or four pages and then in irritation threw the play on to the floor, put out the candle, and drew the bedclothes over him; a little later, after thinking over it, he took the play up again and began to read it; then, getting angry with the uninspired tedious work, he again threw it on the floor and put out the candle. A little later he once more took up the play and read it, then he produced it and it was a failure.

The soil is so good, that, were you to plant a shaft, in a year’s time a cart would grow out of it.

X. and Z., very well educated and of radical views, married. In the evening they talked together pleasantly, then quarreled, then came to blows. In the morning both are ashamed and surprised, they think that it must have been the result of some exceptional state of their nerves. Next night again a quarrel and blows. And so every night until at last they realize that they are not at all educated, but savage, just like the majority of people.

N., a teacher, on her way home in the evening was told by her friend that X. had fallen in love with her, N., and wanted to propose. N., ungainly, who had never before thought of marriage, when she got home, sat for a long time trembling with fear, could not sleep, cried, and towards morning fell in love with X.; next day she heard that the whole thing was a supposition on the part of her friend and that X. was going to marry not her but Y.

“Mamma, Pete did not say his prayers.” Pete is woken up, he says his prayers, cries, then lies down and shakes his fist at the child who made the complaint.

A passion for the word uterine: my uterine brother, my uterine wife, my uterine brother-in-law, etc.

N. all his life used to write abusive letters to famous singers, actors, and authors: “You think, you scamp,…”—without signing his name.

A lady grumbles: “I write to my son that he should change his linen every Saturday. He replies: ‘Why Saturday, not Monday?’ I answer: ‘Well, all right, let it be Monday.’ And he: ‘Why Monday, not Tuesday?’ He is a nice honest man, but I get worried by him.”

Russia is an enormous plain across which wander mischievous men.

N. has written a good play; no one praises him or is pleased; they all say: “We’ll see what you write next.”

Merrily, joyfully: “I have the honor to introduce you to Iv. Iv. Izgoyev, my wife’s lover.”

N. makes a living by exterminating bugs; and for the purposes of his trade he reads the works of —————. If in “The Cossacks,” bugs are not mentioned, it means that “The Cossacks” is a bad book.

A man, forty years old, married a girl of twenty-two who read only the very latest writers, wore green ribbons, slept on yellow pillows, and believed in her taste and her opinions as if they were law; she is nice, not silly, and gentle, but he separates from her.

When one longs for a drink, it seems as though one could drink a whole ocean—that is faith; but when one begins to drink, one can only drink altogether two glasses—that is science.

The crying of a nice child is ugly; so in bad verses you may recognize that the author is a nice man.

A girl writes: “We shall live intolerably near you.”

Success has already given that man a lick with its tongue.

"N. has fallen into poverty." — "What? I can't hear." — "I say N. has fallen into poverty." — "What exactly do you say? I can't make out. What N.?" — "The N. who married Z." — "Well, what of it?" — "I say we ought to help him." — "Eh? What him? Why help? What do you mean?" — and so on.

N. and Z. are school friends, each seventeen or eighteen years old; and suddenly N. learns that Z. is with child by N.'s father.

He looked down on the world from the height of his baseness.

"Your fiancee is very pretty." "To me all women are alike."

N., father of a family, listens to his son reading aloud J.J. Rousseau to the family, and thinks: "Well, at any rate, J.J. Rousseau had no gold medal on his breast, but I have one."

N. has a spree with his step-son, an undergraduate, and they go to a brothel. In the morning the undergraduate is going away, his leave is up; N. sees him off. The undergraduate reads him a sermon on their bad behavior; they quarrel. N: "As your father, I curse you." — "And I curse you."

When I become rich, I shall have a harem in which I shall keep fat naked women, with their buttocks painted green.

•

Twenty-six items from Special Collections