Resurrectional poetics

A review of Raúl Zurita's 'Dreams for Kurosawa'

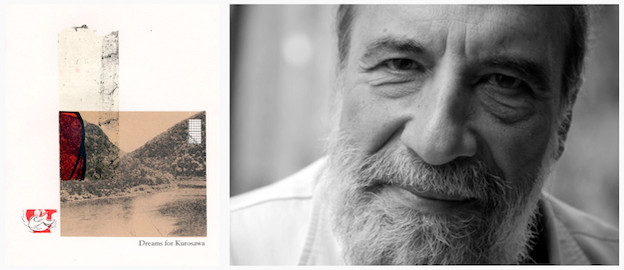

Dreams for Kurosawa

Dreams for Kurosawa

Raúl Zurita’s Dreams for Kurosawa belongs to a very small genre of what might be called “posthumous poetics.” Its practitioners are few: Dickinson, of course, but also Rilke, Celan, and Beckett. It was Roland Barthes who, in “The Death of the Author,” consigned the persona of the writer to the grave of textual effects, a symptom of the cult of authorship and the chain of its material production, distribution, and reception. But it was also Barthes who resurrected the author out of a desire for his presence, a desire to call back the ghostly trace into the warmth of human company. For Barthes, the text sometimes permits a transmigration, as he calls it, from the author to the reader. It establishes a coexistence.

In Dreams for Kurosawa, Zurita writes toward this coexistence from the other side of consciousness, a place to which the living have been disjected, but which poetry stubbornly reclaims. It is a place endowed by language with faith in being’s persistence, which is not the afterlife at all, but the voice of the poem as it speaks from the flow of logos, lit by a mortal darkness.

In these harrowing and ecstatic poems dreams of dying and resurrection commingle promiscuously. The presiding angel of these scenes of repeated nullity and affirmation is Akira Kurosawa, whose film Dreams allowed Zurita to imagine the possibility of a life after the brutal dictatorship of Pinochet, who seized power in Chile in 1973 through a CIA-backed coup. For Zurita, this sorrowful territory underlies all he has written since 1979’s Purgatory (also translated by Deeny). His imprisonment and torture were etched, most memorably perhaps, in the ephemeral skywriting poems of 1982 that appeared over New York City, spelling out “My God is Cancer / My God is Emptiness / My God is Wound / My God is Ghetto.” Dreams for Kurosawa is in some ways a less radically formal book (the poems have been assembled from three separate collections). But their seemingly calm hypotaxis belies the excruciating trauma that informs them.

The calm emanating from these poems is eerie, though. Emotion recollected through loss, not tranquility. Zurita’s primal aesthetic scene, as it were, is drawn from Kurosawa’s film and provides him with an image by which he can begin to address the horror of Pinochet in a new key: a squad of Japanese soldiers emerges from a tunnel and are confused to find that they are dead, and the war over. Like the soldiers, these poems wander restlessly through a posthumous landscape, searching for the remnants of the life they once knew. Unlike the lost revenants however, who must return to the darkness of the tunnel, Zurita depicts his former life with an incandescent glow, albeit stained with profound melancholy:

I saw the first cities of water heading north, in Atacama.

They were suspended in the sky, like gigantic

transparent aquariums, and the luminous reflecting

lines swayed on the ground covering the immense

ocher plane. It was 1975, the end of summer, and I

suffered then. (“Poem 5”)

Suffering haunts these poems with recollected pain and the yearning for the lost object. It is that very yearning which constitutes the poet’s resurrectional poetics. His family and friends come back once more, vivid with life, as in a dream. Yet the matter-of-fact tone, which moves between calm dignity and anguish, imparts both a piercing immediacy and a kind of finality to these scenes, preserving the distance death imposes even as it strives to close that distance. The dreamer suddenly wakes and realizes he’s been dreaming:

Now he had died and

I dressed him while mother and sister waited in the

living room. As I opened the door to tell them they

could come in the fury of the wind and hail thrashed me

stunning me and blind I ran across the field. Kurosawa,

I cried out then, he returned to die again with me.

As I opened my eyes above me I saw the dizzying

white of the summit and much further below the first

lights of the city illuminating. Only then could I cry.

(“Poem 12 — Papa Has Returned”)

Moving with the logic of dreams, their sudden shifts in register, their condensing of time and place, these poems are cinematic and fluid, a continuous montage of images culled from a childhood of deserts and waterfalls, life in the city, life under the tyrant, and the liberating interior life that only the movies can give us. Like the movies, poetry lets us live out a second life. We may die, but we can still be called back. For the dead in fact are never gone; they are the ones who are always returning. The crisis of living is in how we remember them — the shame and struggle of remembering them — and how we also look ahead into the horizon of our own finitude.

This is a beautifully crafted book, with hand-sewn binding and individually silk-screened covers, produced by Michael Slosek and Luke Daly’s arrow as aarow press in Chicago, and translated with extraordinary sensitivity by Anna Deeny. In her eloquent afterword, Deeny links Zurita’s resurrection poetics to Paul de Man’s explication of the central trope of poetry, prosopopeia. For Deeny, the act of poetic figuration “marks the ultimate limit of the self that is death at the same time that it imposes a greater concern for the limit of the other, that is, the other’s death.” In Deeny’s reading, Zurita’s concern for the other, what he himself calls “the resurrection of the dead,” aims toward and is affirmed by “language’s infinite yes.” But getting to that ‘yes’ means dying.

As I opened

my eyes my small body floated at the base of

the falls, and it wasn’t a dream Kurosawa because

I was dead and the waters were tearing me apart.

(“Poem 4”)

Then my eyelids froze, I saw the dark blue of the

sky open up above me, I tried to tell them and died.

(“Poem 17”)

As I

got up I noticed I couldn’t move my arms frozen

beneath the snow. Kurosawa, I said, I was just a

typewriter salesman and now I’m dead and it snows.

(“Poem 19”)

Dying is the central predicament of these poems. It occurs over and over, with the repetition compulsion that colors dreams. For Zurita, dream is the portal to the imaginary of the afterlife, its capricious logic reenacting scenes of catastrophe and rescue through recurring images of the sea, waterfalls, the Atacama desert, Pinochet, and the poet’s deep sense of shame at having died only to come back again, forced to relive his trauma. A sense of lucent vertigo carries these twenty-three poems forward. Their brisk narrative pace has the momentum of a diary composed under duress. Laid out in block-like single stanzas, each roughly twenty-five lines long, their regularity reinforces the power of repetition, of a compulsion to retell the same scenes, the poem pushed to the point of exhaustion and, beyond that, to a floating transparency, to the voice of a recording angel that both inhabits and testifies suffering.

Then I plunged in

and saw that the sea was endless plains of

torsos and backs exhumed, of stomachs that

waved like rags extending themselves to the

horizon …

they were millions

upon millions of faces with their mouths open,

infinite hips, arms and legs sweeping again

and again the beach as if painted ropes. Kurosawa, I

managed to cry out, this isn’t a dream, this is the sea.

(“For Kurosawa/The Sea”)

Raúl Zurita’s sea is both an actual repository of the victims of Pinochet’s cruel regime — not a dream at all, but the nightmare of history — and a surreal site beyond sitedness, where the dead are received, first as the mangled corpses of massacre, then as the hallows of living memory. They do not so much haunt the poet as allow him to reimagine what it means to be. In a word, they are messianic, since their return intervenes in the trauma of their violent deaths, re-potentiating the present for those who, like Zurita, can still speak for its dream of becoming.