Against elegy: Michael Palmer's Book of the Dead

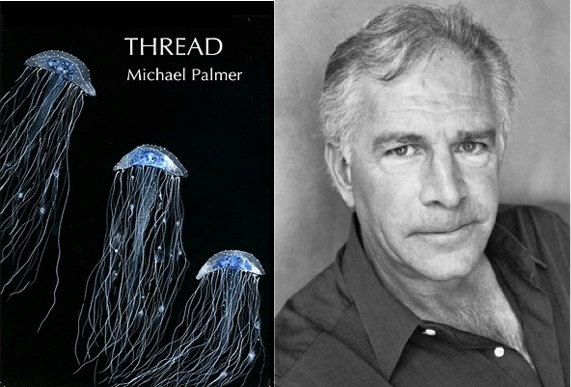

A review of 'Thread'

Thread

Thread

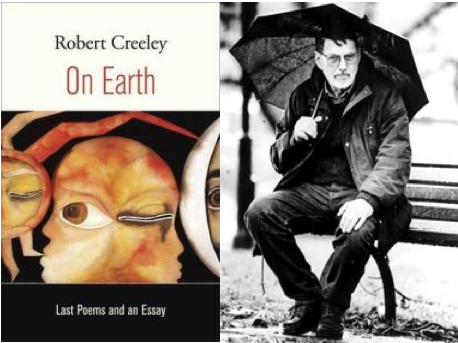

“Thread — Stanzas in Counterlight” is Michael Palmer’s Book of the Dead. The title series of his ninth full-length collection, these eighteen interlinked poems are not elegies in the traditional sense. Neither songs of lament, nor, strictly speaking, commemorations for the departed, they reconfigure the genre. In these extraordinary poems, among the most moving and powerful of his career, the dead appear as companions on the way, intimately joined to the enterprise of living. Thread transforms elegy into crystalline paleography — a writing before writing that is also beyond it. Here, the customary polarity between innocence and experience is reversed. Innocence is not what is lost; it can only be gained. It does not precede experience, but is produced by it. For innocence is not a category of purity outside the travails of experience, but a condition that is achieved only by passing through the sorrows of an arduous contingency. The poems in Thread amply testify to this. In “Transit,” for instance, the sight of Creeley’s final book, On Earth, spurs a mournful, yet consoling, recognition.

We’ve come

to the old

echoes again,

swallowed songs,

tongues of cloud and wind.[1]

The delicious image of a “swallowed song” rides on a cascade of vowels. The old echoes go with us, through us, speak out of us, again. So many of these poems feel like fragments of an overheard conversation. Nearly every one of them trails a ghostly double, beckoning us, in their uncanny incompleteness, to listen for further, unheard melodies. In “Fragment After Dante,” the first of a three-part series, the poet finds himself stranded in the realm of shadows: “And I saw myself in the afterlife of rivers and fields / among the wandering souls and light-flecked paths” (34). Amid the suffering of the dead, the greatest torment is to hear them speak, “chatting about nothing,” yet failing to understand them. The second Dante fragment resonates with muted pain.

And she clasped my arm and said,

You, my son, who have lingered

too long among the dead, go

and return to the lighted shore

for those brief moments you have left. (35)

In a haunting image, the speaker’s face transforms “from old to young” as she vanishes. Memory’s dream of what-was mingles promiscuously with its hope for the Not-Yet. Throughout, Thread generously acknowledges that its every word is merely on loan from “the thief’s journal,” Palmer’s phrase, by way of Genet, for the floating para-text of unowned language. This is elegy against elegy: not a quixotic defiance of mortality, but a deepening awareness of it; a way to write into and out of finitude.

Thinking of the dead this way enables Palmer to do away with appeals to the cult of the personal and its fetish for the unique. “The dead” in these poems name an experience in which loss is only another form of continuity. They are always near and yet irreparably distant. In this way, the poem occupies a Rilkean angelic topos: it circulates freely between the living and the dead without making any distinctions between them. To speak the dead this way is to place them in an order of belonging beyond sentimental coercion. They remain strange and vivid; sheltered within memory, but also outside it; irrefragably singular.

Thread inhabits the melancholy landscape familiar to Palmer’s readers, a place where language ratifies itself by signifying its own failure. Written under the agonizing sign of Saturn’s slowness, they are harrowing in their humility and directness. Simplicity here is neither a reduction nor a retreat, but the earned complexity of a late style in a late hour. To call “Threads” a tour de force would only defame it. These “threads” are addresses, colloquies, homages — unanswered questions that concentrate Palmer’s concerns for his art as a site for making counter-meanings, those micro-resistances that push back against the crushing sense of moral fatigue born of loss, suffering, and slaughter.

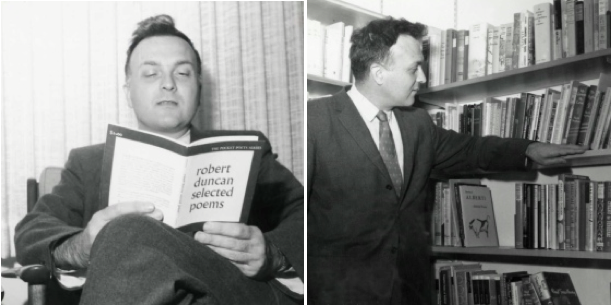

The “stanzas in counterlight” bring together reflections on the possibility of art with poems to fellow writers such as Robin Blaser, Gustaf Sobin, Alexei Parshchikov, Roberto Bolano, and Mahmoud Darwish. In tone and imagery, the series calls to mind At Passages’ “Six Hermetic Songs,” his elegy for Robert Duncan and perhaps the inaugural poem in his Book of the Dead, though it seems he’s always been writing this way, “ahead of all departure.” With its prayers of intercession and spells for safeguarding the soul’s passage through the underworld, Palmer models his own funerary chants for Duncan after The Egyptian Book of the Dead, guiding the older poet into the afterlife of language.

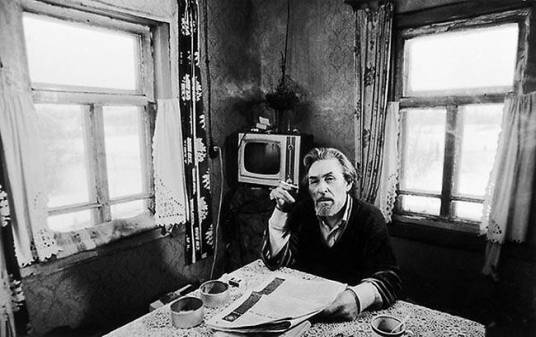

Photos of Robert Duncan by LaVerne Harrell Clark via University of Arizona Poetry Center.

It’s worth dwelling on the Duncan elegy. “Six Hermetic Songs” begins with an epigraph, taken from The Book of the Dead’s chapter “On the Coming Forth by Day.”

Bring along the Makhent boat

for I have come to see Osiris

lord of the ansi garment [2]

This ritualistic language sets the scene for the six sections to follow, each of which charts a stage on the soul’s journey through the hazards and judgments of the underworld in its progress back toward day. Here is the first poem of the series.

How did we measure

it says we measured up and down

from the sepia disk

to the crowded ship

of Odysseus

How did we measure

it says we measured

with a copper thread

from the plum flower

to the forgotten gift

Was the tain’s smoke

equal to song

the vein of cedar

to a pin’s bones

Burns each

earlier day

in its soundless weight

measured by the nets

of air

Go there.[3]

The haunting cadences of this solemn poem sound a plangent note, its clipped, roughly five-beat lines counting out a purposeful, liturgical insistence on the body as it remembers gravity, its weighted measure, kept whole by cedar yet dissolved in the “tain’s smoke,” the mist of song passing over a mirror as the last syllable is uttered. As Palmer frames it, measure (or metron) names a messianic splice for keeping time in the poem by interrupting it. The final — “Go there” — commands the dead poet to take passage in song’s “nets of air.”

The measure of the poem here is not made according to traditional prosody, but by what Palmer elsewhere calls the Laws of Forms, that responsiveness of “the poem’s eternal stance against passive subjectivity, against the given, on behalf of the unspeakable and the unheard.”[4] Duncan appears as the keeper of this measure, both by the example of his work and through his role as a guardian of ancient and esoteric knowledge. More than that, though, measure names the predicament of poetry as it confronts the limits of its own saying. In the third poem the older poet speaks, recalling his vanished life:

The calls and careless fashioning,

digits thrown like dice

I don’t think about that anymore

Send me my dictionary.

Write how you are.[5]

For Duncan, the arch-mage of postmodern poetry, the dictionary is nothing if not a book of spells, a grimoire by which the poet might conjure a world, or rather, a web of subtle connections between past and present, the vanished and the visible. The suggestion that Palmer’s mentor has entrusted him with his dictionary implies both the passing on of a lineage and a plaintive cry for the restoration of dear earthly objects, like the ones the Egyptians placed in their tombs to ease the dead’s voyage over dark waters. More than that, the dictionary signifies the limitless potential for bibliomantic conjuration, the thief’s journal par excellence.

The final poem of “Hermetic Songs” is a kind of summoning: a voice, calling over water, over distance, either in final farewell, or hailing return.

The wrecked horn of the body

and a water voice

The horn of the body

and a slanted water voice

The notes against the gate

and the erasures of the gate.[6]

H.D. (undated), via Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

A complex set of echoes is put in motion here, recalling Duncan’s own “After a Passage in Baudelaire” (”Ship, leaving or arriving, or my lover, / my soul, leaving or coming into this harbor”), and back of that, the closing lines of H.D.’s Vale Ave (“I ask for this, the blessing of the Ship, of the ‘Parole,’ / in remembrance of the seven times we met”).[7] “The wrecked horn of the body,” like the Jewish shofar, names both an exalting music and the unyielding stuff of obdurate matter. “Six Hermetic Songs” closes with a set of interrogative affirmations, asking “Whose night-songs and bridges // and prisms are these.”

What figures within the coil

tortoise and Bennu bird

lotus and hawk

palette plus ink-pot.

The Bennu Bird is the Egyptian phoenix, a figure associated with rebirth in an afterlife, while the lotus signifies “the divine splendor that belongeth to the nostrils of Ra,” that is, to the body’s breath, its divine measure.[8] The final image is of the poet composing himself with his familiar ink-pot in the resurrected life, writing beyond the ending.

I’ve revisited “Six Hermetic Songs” at such length because “Thread — Stanzas in Counterlight” so strongly echoes and carries forward its concerns. In the manner of Duncan’s own Passages, these poems ask to be read together, across their separate volumes, as parts of a single work. The first and twelfth poems in the series glow with the same kind of heraldic language that marks “Hermetic Songs.”

Nighthawk and sun-bird

beauty of the world beauty of the world

How can one write beauty of the world? (75)

And:

Nighthawk and sun-bird

Who will tell of it

Shore’s eyelid, earth’s rim

light from extinguished stars

bathing us

in time’s wake

time’s long

stream of slaughter

and song

Some love

the one more

some the other. (87)

Thread is lambent with such figurality. The recurring figures of the bird, the fountain, the book; of Babylon, the moth, the lovers — these are ideas as character, emblems of a spiritual imaginary that supersede and amplify the earlier work’s immersion in linguistic metamorphology. Utterly transparent, they militate against concretion, yet their very clarity renders them enigmatic. They carry over Palmer’s analytic lyric into the key of allegory.

In these poems figurality is the idea of form itself. The ideal of correspondence so dear to Baudelaire migrates from the hermetic notion of a mirror that reflects the heavenly in the earthly and the earthly in the heavens, to the fructifying dissonance between word and thing, past and present. Loss prefigures redemption, of course, but only as muted whispers from the realm of ghosts. A devoutly secular alchemist of the word, Palmer invites traffic with the transformative powers of the strange, even as he confutes all claims put forward on behalf of a tyrannical spiritual orthodoxy.

Tenses of the present, Mahmoud, the (im)possible

present, infinite presents threading

now forward, now back. Amidst the

shattered symmetries and scattered fictions,

between actual river and imagined shore,

actual breath of wind through the frayed (91)

The present is the infinite — expansion of the actual into the imagined, the imagined into the actual. If there can be no final truth, or if it is only and already imperfectly figured through language, the dream of alteriority nevertheless persists, in large part because language is structured to imagine its own outside. As a system for shaping interiority by organizing experience, its logic is geared to continually surpass and subvert its own boundaries. Language is thread, and nothing but — weaving, unweaving, reweaving.

The idea of the thread runs throughout Palmer’s poetry, integral to his project for building “threads of speech and constellations of sound … rather than a single, unitary voice.”[9] The opening of “Baudelaire Series” attests to this, speaking of “the mechanism of the larynx / around an inky center / leading backward-forward // into sun-snow / then to frozen sun itself / Threads and nerves have brought us to a house.”[10] And further on in the same poem we find the Palmerian locus classicus:

What if things really did

correspond, silk to breath

evening to eyelid

thread to thread.[11]

What marks this chain of likenesses is their unlikeness. Baudelaire’s dream is accomplished, not by an intimate metaphysics, but through a language of dissimilarity. Thread’s allure as a constellating trope, its ability to articulate a grammar of correspondence between unlike things, forms the core of Palmer’s conception of language and its polymorphously perverse power to link by way of dissonance. If silk is a synonym for breath, then evening imitates the action of the eyelid, closing over the field of vision. “Thread to thread” promises an exact equivalence, a braiding of identical things. Yet the necessity of repetition casts a shadow between the first and the second instance of the term. “Thread to thread” invites connection, but the slippery preposition can equally signal a gap.

To thread, then, is to work midrashically, for these poems take up Palmer’s abiding concerns with the necessity for dispersing the subject and the concomitant counter-struggle to preserve its singularity, if only as a remnant. In Thread, the figure of the book appears as a messianic object, braiding together now with then, here with there, in a suspension of time where the words of the dead are spoken as one’s own even as the dead speak through the lips of the living. This bewitched chiasmus in many ways defines Palmer’s project, his desire to dissolve and connect, forget and remember, to “add yourself jubilantly, and erase the score,” as Rilke puts in Sonnets to Orpheus. Only in this way can the poem resist succumbing to mere introspective reverie.

Late style in Palmer is not the willful intransigence Adorno admires in Beethoven’s final works. Rather, it is a deepening of themes, a move toward a radical simplicity, a return, in other words, as in a sonata, to first statements, in the key of clarity. In a 2006 interview with Ken Bullock, Palmer describes the trajectory of his poetry as “moving a little bit away from radical syntax into the mysteries of ordinary language, in the philosophical if not every day sense. It probably looks less unusual on the page. And I’ve been interested in the infinite, ingathering potential of the lyrical phrase — not confession, but the voicing of selves that make up the poetic self, from Greek lyrics to the Italians, to modern poets like Mandelstam.”[12] These are the same concerns that have marked his strongest work all along, most notably “Baudelaire Series,” which according to Palmer investigates lyric from Hölderlin on. But if Palmer has moved away from explorations of linguistic syntax, he’s taken up in turn the serpentine syntax of dreams, whose logic is a yearning for a replenishing otherness, as in “Broad Waking.”

Slant from the poem’s mouth

Atlantis arrives, the cries

of children arise, the dance

begins, perfect circle of the

squared poem, its cardinal

points, stillness and motion

and the singing against time,

the dancing in time,

the ringing in our ears,

the silence as the waters rise (47)

The oneiric landscape rises, a figural domain porous with primal interiority. Closer to Gennady Aygi (another poet honored in this book) than George Oppen, it hews all the same to the Objectivist credo of austere minimalism, the sense that each word can be arrived at only through patient struggle. Late style in Palmer is a slow concrescence, an exactitude of means.

Gennady Aygi image via Beijing Language and Culture University.

Along the corridors

of the invisible world, Raúl,

gardeners raise such flowers

as need no light

such flowers

watered by voices

as need no eyes

to be seen. (79)

In this poem to the Chilean poet Raul Zurita, whose most well known work, Purgatorio, recounts the nightmarish imprisonment the poet suffered under the Pinochet regime, the invocation of “the invisible world” where “flowers need no light” but are instead “watered by voices” for the eyeless, attests to the necessity of an inner, allegorical landscape where poetic language can still radiate, free of tyranny and oppression. “The invisible world,” one might say, is the place where disaster is rewritten in a language that translates suffering into the spectrum of recognition.

Similarly, the poem to Robin Blaser attends to the intimate undertow of a poetics that knows all it says is said in the shadow of its own vanishing.

The moth, Robin,

we’ve both learned

at different times

from its motion, a

quantum of nothing

could we say,

dusk to dark morning

before full day,

a battering of wings,

night notes sounding

beyond our extinction

Moth verges on and merges with mouth, an image of transience and longing fluttering in its “quantum of nothing,” a figure for speech “sounding / beyond our extinction” (81). But this is a sounding that also utters hesitation, each comma starkly denoting the pause of breath in a poem that otherwise refuses final punctuation. Narrow constructionists, the kind of readers who’ve made idols of Sun or Notes for Echo Lake, might deride these slender poems as a falling off, but I find them incredibly moving. They represent the distillation of a lifetime’s attendance to the nuances of a luminous art written under the sign of shadow.

Moth verges on and merges with mouth, an image of transience and longing fluttering in its “quantum of nothing,” a figure for speech “sounding / beyond our extinction” (81). But this is a sounding that also utters hesitation, each comma starkly denoting the pause of breath in a poem that otherwise refuses final punctuation. Narrow constructionists, the kind of readers who’ve made idols of Sun or Notes for Echo Lake, might deride these slender poems as a falling off, but I find them incredibly moving. They represent the distillation of a lifetime’s attendance to the nuances of a luminous art written under the sign of shadow.

What Palmer accomplishes in this book is the meaning of being haunted, poetically – the way a poem burrows into us, becomes an intimate part of our psychic life. Haunting in this sense is not some stubborn refusal to move on after grief. Rather it is an active form of melancholy, a rejection of the proscriptive hygiene for mourning and its insistence on the palliative. It is not a morbid keeping open of the wound, but a preservation of the dead as a still vibrant field of interior force. Far from memorializing loss, it incites recognition. For loss to be loss it must abjure closure. The coda-like lyric for Gustaf Sobin poignantly bears this out.

Gustaf, under earth

by the tiny grave-pits

Merovingian words we

speak by the plague wall

by the house of the suicide

by the Mount of Winds

sits the low house of stone

lies the silk-maker’s house

thread spun and gone.

Words are the distant home. (92)

The enjambed syntax performs a liturgical rite, redeeming spirit in a house of words where melodic frequency is attuned to estrangement’s deeper belonging, its “distant home.” The sense of desolation is powerful here because so carefully modulated. It’s consoling, as only the bleakest measure can be.

This thread of threnodies calls to mind, of course, Duncan’s Great Companions, a theme noted by Geoffrey G. O’Brien in his perceptive review of Company of Moths. In that book, a trend that has always marked Palmer’s work, but which only moved to the fore in At Passages, became more pronounced — namely, his shift to a distinctly bardic register. This shift has gone largely unremarked on, though Norman Finkelstein gives a good account of Palmer’s relation to Duncan’s poetics in his recent On Mount Vision. What does the bardic in Palmer look like? As I’ve already suggested here, it partakes of a heraldic vocabulary, a secular typology that inverts the polarity between thing and word. Here is the sixth poem in the series:

It is the role of the lovers to set fire to the book.

In the palm garden at night they set fire to the book

and read by the light of the book.

Syllables, particles of glass, they pass back and forth in the dark.

The two, invisible - transparent - in the book,

their voices muffled by the book.

It is the role of the lovers to be figures of the book, the

illegible book,

changing as the pages turn,

now joined, now clawing the fruit from each other’s limbs,

now interlaced, now tearing at throat and vein,

then splayfoot, then winged, then ember,

as the music of the book,

rustling through the palms,

instructs. (80)

“To be figures in the book,” even as it burns, even as its burning illuminates the words on its pages, is to guarantee the promise of “the invisible world,” where the poem is continually remade through a kind of doubling , echoing and re-echoing in a gallery of citations and counter-citations. The book, Palmer understands, will always be “illegible;” its burning at once a source of illumination and obscurity; a figure of music alternating between the “splayfoot” and the “winged,” and written in an alphabet whose transparency is only the others side of the invisible, “the muffled.” It must be that which, even in its plain saying, remains hidden, a zero of logic “rustling through the palms.” The book as music. Perhaps this is what I’ve been trying to say here all along.

And I’ve said nothing about the rest of the book. Scattered with the kind of amusing bagatelles Palmer has always written, the highlights of the first section, “What I Did Not Say,” are the three series, “The Classical Study,” “Say,” and “Aygi Cycle.” The first of these features a playful figure called The Master, a kind of trickster male muse who calls to mind both Duncan himself and his Master of Rime: “The Master of Rime told me, You must learn to lose heart. I have darkened this way and you yourself have darkend. Are you so blind you cant see what you cant see?”[13] Gnostic endarkenment subducts the poem into telluric currents of language. Or, as Palmer writes, it’s a game “where silence matters / above all, or do I mean sound?” (6).

“Aygi Cycle” stands apart from and alongside of “Thread.” These ten short poems are a kind of prelude to the longer series. Here Aygi is refracted through the lens of Oppen and Cezanne. The fragility of a single word becomes the very source of its power. It does not attempt to mean, since meaning is too fraught a task, only to persist somehow before its own imminent disappearance. At that wavering boundary line, the indeterminate zone between affirmation and negation, the word hovers, as in the Cycle’s fifth poem:

Within the small poem time

and tales of the preening gods

among the sliding stars

and love’s silent

mirror held up

to the crimes of war

within the small poem (58)

As the tender of silence and smallness, Aygi watches over the garden of ruins, where renunciation opens the portal to the field of the other. In Palmer’s reading, Aygi makes of childhood a space for “entering into awareness and into speech.” His Aygi is brought into conversation with Oppen’s elegy for Reznikoff, where the poem is written “in the great / world small.” Another thread woven, glimmering.

In Thread the dead are not the departed, but those who go along with us. Asymmetrical, they map the jagged experience of living onto the impossible promise form makes to spirit. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the soul is made ready to pass judgment before Osiris before it can “come forth by day” into a second life. The poems in Thread are that second life, the small place, as in “After Hölderlin,” where, concealed from day, abiding in silence:

One must wait

to draw a night song from these names,

the then and the now, the dark and light

as they alternate, just out of reach. (41)

[1] Michael Palmer, Thread (New York: New Directions, 2011), 65. All subsequent page references will be placed in parentheses.

[2] Palmer, At Passages (New York: New Directions, 1995).

[4] Palmer, Active Boundaries: Selected Essays and Talks (New York: New Directions, 2008), 80.

[7] Robert Duncan, Roots and Branches (New York: New Directions, 1964), 77; H.D., Vale Ave (Redding Ridge, CT: Black Swan Books, 1992), 76.

[8] The Egyptian Book of the Dead, trans. E. A. Wallis Budge, 20, 263.

[9] Philip Dow, 19 New American Poets of the Golden Gate (New York: HBJ, 1984), 341.

[10] Palmer, Sun (Berkeley, CA: North Point Press, 1988), 9.