The quiet influence of patience

A review of Linda Norton's 'The Public Gardens'

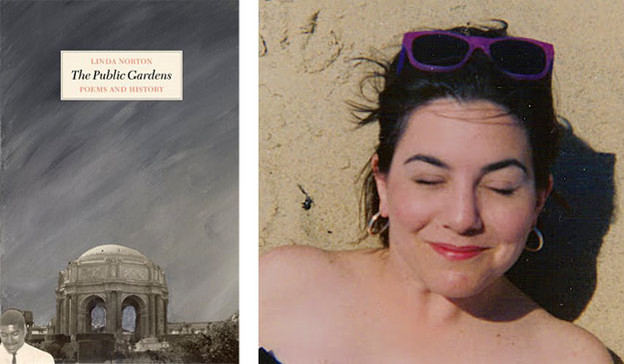

The Public Gardens: Poems and History

The Public Gardens: Poems and History

Prior to the publication of Linda Norton’s 2007 Etherdome Press chapbook, Hesitation Kit, and her 2011 Pressed Wafer book, The Public Gardens: Poems and History, which was a finalist for the 2012 Los Angeles Times Book Prize, many readers didn’t know that Norton had already exerted a quiet influence on them in her work as a poetry editor at the University of California Press. Since the 1980s Norton has made her living as a publicist and editor for a variety of publishing houses. Today, she works at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley, California. All these years, as the reader learns in The Public Gardens — a book that begins with poetry, continues with journals from the late ’80s into the early ’90s, and finishes with more poetry — she was writing and making collages, though few people were aware of this work. As Norton put it in a 2010 interview with Kate Greenstreet, “I like to do readings because I like to participate, to contribute, and I often hear people say, ‘I had no idea you wrote!’ or ‘I had no idea you were a visual artist!’” Norton’s response suggests that she prefers the communal to the individual, a preference that provides shelter to work without the burden of attention. Without a doubt this communal impulse shapes the interrogative quality of Norton’s writing.

Many of the concerns in The Public Gardens start to crystallize in “Landscaping for Privacy,” the first section of the book. Two of the most recurrent themes center on the question of what it means to be a woman who is first a girl and how to make art. The poem “Rose with No Name” contains these lines:

Red roses on a rose bush looped with garden hose —

The first paintings were made with blood,

beauty out of carnage, or was it red ink

from the body of the first girl, from the first

wondering about what was happening

and how it might look and how it might smell.

Throughout The Public Gardens Norton shares with her readers the sense of wonder found here. This sense, though, is not clouded by fanciful idealism or lofty dreams. The earthy wonders are life and the art that people make from it. Norton’s speculations in this poem along these lines are fascinating. Were the first paintings made with blood got from killing? Or, more powerfully, were these paintings made with the menstrual blood of a young girl? As the poem continues it’s clear which question bears further interest:

The heirloom roses in this garden smell old

which means they smell fresh as the first girl

unlike some of the new roses bred to blossom

thornless, fast, synthetically, to resist pests.

Norton goes on to write that these synthetic roses “smell of money and garden hoses” and that “anyone / could do it, could do them; pornographic. / The first girl, the first rose: Sapphic.” In addition to Norton’s focus on the role women play in the arts, these lines mark yet another concern in The Public Gardens: authenticity. Norton often arrives at what she considers genuine by asking questions.

In the prose section of the book, entitled “Brooklyn Journals,” many of her queries focus on the burden of class. It’s particularly clear why in a passage dated October 11, 1987, where she’s reflecting on an interaction with her younger brother, Joey:

He glamorized my conventionality, my oldest sister ways, my pious lapsed Catholicism and my working-class pedestrian nature. But he knew this was not a pose established in order to subvert the establishment. It was something real and stolid and unconscious, something that made me old, and I hated it while I defended it.

The fact that our pasts are real and unconscious mean that they follow us wherever we go like unleashed dogs that somehow know the way home. Norton is always conscious of this in her work.

In her journals it’s particularly compelling how Norton depicts her siblings and their reactions to their shared upbringing. Joey wanted to escape it. Near the end of the October entry Norton recounts the moment when her brother picked up her gloves she had bought at Filene’s Basement: “‘Vinyl,’ he said, smelling the gloves. ‘Can’t you at least try to get real leather gloves?’ I frowned. I hadn’t realized they weren’t made of leather.” This is another of Norton’s strengths, her self-deprecating sense of humor.

Within this frame of class and sibling tension comes perhaps the most startling thread in The Public Gardens, an unfolding story of Joey and his death from AIDS in 1986. In the first journal entry of the book dated May 10, 1987 Norton introduces readers to Joey, or Joseph as he’s referred to in the entry, with an insightful comparison of her and Joey’s notes in the margin of Ulysses — the copy is Norton’s and Joey has borrowed it. Her notes were “parochial — all about Catholicism — the intense familiarity, though we were Americans, of Joyce’s Irishness, names and rituals, guilt and materials,” and his were “all about modernism and European intellectual and literary history.” As “Rose with No Name,” cited above, foregrounds the female, so too does this example, but here the gender difference Norton wants the reader to see is even more direct. Tellingly, the notes Norton made in the margin of Ulysses are recurring concerns in The Public Gardens, and it is a stronger book for it.

In the same October entry discussed above Norton is already asking about Joey’s death: “Was my brother Joseph able to prepare for his death? There was no time. Death by sex, shame, rage.” In the journal entries that follow we learn how bitter Joey had become in his last days. Especially haunting is the entry dated August 23, 1987, when Norton is listening to Duke Ellington’s “Sacred Mass” and remembering that the nurse for her brother at Lenox Hill had told her that Joey’s bed was where Ellington had died. At first, Norton writes, “My brother would have loved to know that.” But, in the following paragraph she rescinds that thought:

No, he would have hated to know that, as he hated everything the last year of his life, spitting at people, even biting my father to try to infect him (he went home, to blame or beg, and my father threw him out; as my parents threw us all out, one right after another). He was trying to leave his goofy older boyfriend, but there was nowhere to go — he’d lost his job after he threw one of his tantrums at work — the job he loved, editing guides to the national parks.

Norton’s entries through the rest of the eighties makes clear how new and confusing AIDS was for her, as well as for society at large. In September 1987 Norton mentions “An emaciated man in a wheelchair with Kaposi’s lesions rolled past me one day in the rain. It’s everywhere. But none of the sick men I see are as young as my brother was. Why?” Then, in August 1990 she touches upon the fact that her family back in Boston refuses to admit that anyone but Joey has died from AIDS, and acknowledges to herself “At least in New York I’m not alone with it.” In the midst of all this the reader learns that Joey died a week before the discovery of AZT.

Norton’s skillful writing in her journals shows the complexity of the AIDS legacy, and more acutely how layered Norton’s difficult memories are concerning her family. The ability to weave these layers as honestly as Norton does in The Public Gardens is rare. How often is one willing to look hard at one’s family and milieu, write about them, and then publish it? Certainly, there are acres of memoirs published every year that proclaim penetrating introspection, but few are as probing as Norton’s.

Alongside entries regarding AIDS, her family, and class Norton also pays considerable attention to issues regarding race and ethnicity in The Public Gardens. In the entry dated October 19, 1990 Norton is waiting for an office-building elevator in Manhattan when a man steps out with “an amazing head of dreds, volumetrically astounding.” Another woman, a suburban blonde, about fifty, awaits the same elevator. Once on the elevator the blonde tries to catch Norton’s eye: “assuming we’ll conspire: ‘These people!’ I look down, avoiding her, because I don’t want to be forced to be white with her.” It’s clear that Norton’s self-awareness, even self-consciousness, is not restricted to class difference or familial tension. It’s as if Norton’s eye specializes in the issues that divide people.

As the journal entries through the early ’90s continue, Norton touches on race and the art world. Much of what she writes on this subject pertains to observations in her then-husband Andrew’s studio and at parties. An entry from June 1992 describes an afternoon with Andrew in his studio when they receive a phone call for his studio mate:

The phone rings and these days it’s always someone asking for Hodge Park. It is currently extremely cool to be anything but white in the art world. I half expect him to start using Ho-jun, the Korean name his parents gave him.

Then in May 1993 a painter friend, Steve, and Nancy visit Norton and Andrew at home. At some point during the visit “the guys grumbled about the plight of young white men in the art world — there’s no place for them now.” On the surface these examples seem to be only about race, but they are also about gender, particularly the white male version. Norton delivers her criticisms on this matter in the book brilliantly by simply observing and writing down what she sees and hears. If one misses what she’s after it’s the fault of a shallow reader.

The most wonderful journal entry comes on June 18, 1994, offering a bit of levity in regards to some of the heavier moments dealing with race and ethnicity. At the time, Norton is five months pregnant, on a business trip to London, and alone. As she’s walking down a road lined with tall row houses in Camden she encounters a young man, “high,” Norton guesses, “but not murderous, or insane,” so she relaxes. He asks, “How are you?” In her response he realizes she must be American, and then wants to know where she’s from. “Brooklyn,” she says. Interestingly, this young man is aware that Baruch Goldstein, “the guy who massacred Arabs in the mosque in Hebron,” is from there, too. Internally, this causes Norton to become a little tense, especially when the man asks, “Are you Jewish?” After wavering on how to answer, Norton replies, “No, I’m not Jewish.” At this point, the man “stopped and scrutinized [Norton’s] face intensely, like a surgeon accustomed to handling warm, throbbing ethnicities with his bare hands while the clock ticks.” The man is spot-on when he asks, “Irish and Sicilian?” When Norton expresses her amazement at his expert “ethnic dissection,” as Norton calls it, the man laughs and asks her “to drop some acid with him.” Norton points out that she is pregnant, so they walk “companionably to the corner, where [they] say goodbye, and good luck to each other.” Norton’s terminology, throbbing ethnicities, is perhaps the most accurate way to describe the ancestral forces that shape, at least in part, who we are. More often it seems that one forgets the throbbing part — the fact that ethnicities are alive — and treats these issues coldly, clinically. In The Public Gardens Norton is compassionate and aware. Like the young Londoner she finds a way to bridge this compassion with a surgeon’s grace in her writing on race.

As the journals come to a close Norton gives birth to a daughter, Isabel. Her description, written on November 18, 1994, of the birth is moving, filled as it is with tension and laughter. At the end of the entry Norton describes Isabel’s significance:

It’s not like she fulfills me, exactly. It’s as if her existence, her coming through my body and out between my legs, authorizes me as an animal.

She cries every night for three or four hours, and sometimes I think I’m going crazy. I’m so tired. But her shit really does smell sweet.

In the last section of poems, “The Commons,” Norton continues to share with the reader her relationship with Isabel. “Stanzas in the Form of a Dove,” written in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, moves with feelings of thought and love when she describes an evening she “caught a whiff of Isabel, and realized she needed a bath.” Though tired Norton gives her daughter a bath, puts her to bed. Just when she thinks they’ve both fallen asleep Isabel starts talking:

I have a question about being good or bad. I know you should be good,

but if you’re not, what can

they do to you? I mean, my question is: Do I always have to be good?

Does she always have to be good? When I was a girl, I knew I must

always be good. Because I was bad.

The filth. Look what original sin has done for me.

So I say to her: “No. You don’t always have to be good. You are good.”

She breathes a sigh of relief: “Thank you!” Then falls right to sleep,

smelling so sweet.

It’s startling how continually aware Norton is of her past, and impressive to see her determination to help shape a life that’s distinct to Isabel, perhaps one less burdened by class anxiety and built-in Catholic guilt. The care that Norton takes with each of her subjects in The Public Gardens — the feminine, art making, and family life to name a few — ought to have much influence on her audience. Norton not only applies the attention of her eyes and mind, she also attunes her heart to these matters. Importantly, she’s never afraid to ask questions of her subjects, even if only to herself. In these ways her book is an achievement built on her years of quietly working in the background, which is to say this book is a testament to patience.