'My mother's mother-of-pearl'

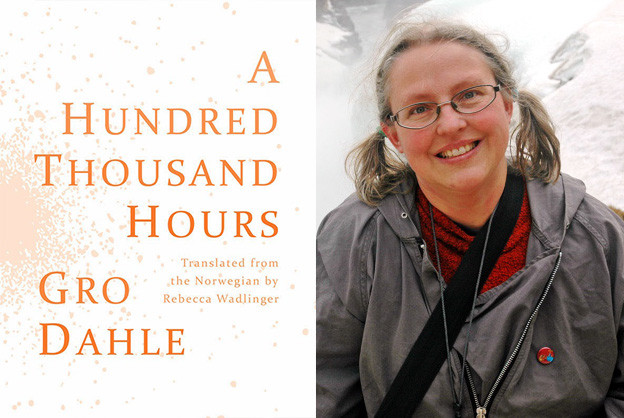

A review of Gro Dahle's 'A Hundred Thousand Hours'

A Hundred Thousand Hours

A Hundred Thousand Hours

The statistics for literature in translation in the United States aren’t good. As Anna Clark, writing for the Pacific-Standard, points out in her article “You’re Missing Out on Great Literature,” a slim 3 percent of books published per year in the US are works in translation.[1] Some readers and translation publishers are already aware of this number. Open Letter, for example, based at the University of Rochester, hosts a blog called Three Percent that focuses on translation-related topics. Interestingly, Clark parses the percentage to show what types of books make up that number. The majority of those works, as it turns out, are computer and technical manuals. After that there are novels, and then books of poetry.[2] It would seem that translators of novels (whether genre or literary) must receive some encouragement from publishers because there is the possibility of turning some profit. For literary translators, though, the money, or the lack thereof, is most likely not the attraction. Perhaps the drive for the translation of technical manuals isn’t from publishers; instead, translators are likely driven by the need from tech companies to provide clear instructional language for users. With such a meager percentage of poetry being translated per year, I started to wonder what role chance plays for poetry translators? How do they discover the work to translate?

For Rebecca Wadlinger, the translator of the recently published A Hundred Thousand Hours, by the Norwegian poet and writer Gro Dahle, chance played an intriguing role in her decision to translate Dahle’s book. Wadlinger, a doctoral candidate at the University of Houston, discovered the Norwegian’s work while on fellowship at the University of Oslo. In an interview for The Kenyon Review, she describes how she found Dahle’s work in the basement of the university library near the end of her stay. By that time, Wadlinger had already read through many books of poems in the library stacks, but when she found A Hundred Thousand Hours she said, “I was floored. I remember marveling at Dahle’s intelligence, morbidity, and imagination. I knew this manuscript would appeal to so many American readers — I needed to translate it!”[3] As fate would have it, Dahle’s book had been out of print for years. Wadlinger decided to transcribe the poems by hand from the Bokmål dialect,[4] an official written standard of Norwegian. So, it’s not simply chance that brought Dahle into English, it’s also Wadlinger’s curiosity in the basement of that library and her commitment to producing a hard copy of the poems to bring home.

While Dahle is virtually unknown in the United States, she is well known as the author of over thirty books in Norway. Audience, her first book of poems, was published in 1987. The daughter of Øystein Dahle, a former executive for Esso and a fellow of the Norwegian Academy of Technological Sciences, she has collaborated with her husband and illustrator Svein Nyhus on a popular series of children’s books. Two of these collaborations have received national prizes in Norway. Nice received the Brage Prize in 2002 and Angry Man, a book addressing domestic violence from a young boy’s perspective, won the Best Children’s Book Prize from the Norwegian Ministry of Culture in 2003. Much of Dahle’s work, whether for children or adults, if these distinctions even apply for a writer such as Dahle, is from the child’s perspective.

In A Hundred Thousand Hours, a book-length work of short poems, Dahle alternates perspectives between the young daughter and the mother she becomes. These perspectives draw from the complexities of a mother-daughter relationship. ‘Complexities,’ though, isn’t quite the right word for a work with lines like these:

I stitch my child onto my body. She is an extra

arm. She is an extra breast. And I breathe

through her. I smile with her mouth.

The world is only as big as the space between

her forehead and my mouth. (79)

Like the above, much of Dahle’s description of the mother-daughter relationship is characterized by spare and direct language that suggests claustrophobic closeness. In the background, as I read these poems, I hear the following refrain: get away from me; I love you.

In addition to her focus on the physicality of the mother-daughter relationship, Dahle creates a constricted atmosphere with her detailed attention to the rooms, furniture, and accouterments that surround the relationship:

When I wake up, the room stands and waits for me.

The moulding, doorsteps and parallel lines. When

morning light falls in a trapezoid on the floor, it touches

the corner of a button. My mother’s mother-of-pearl button.

When I spill sugar on the floor, I take it as a good

sign. But in my side-sight I see the furniture ready to run. (11)

The emphasis on small details, the trapezoidal morning light touching the corner of a button, and the use of alliterative repetition in “My mother’s mother-of pearl button” depict a highly observant daughter. It seems, too, that the speaker attaches a divined, yet panicked, significance to the spilled sugar when she takes it “as a good / sign.” This divination appears throughout the book and often seems to stem from the need for the daughter, and sometimes for the mother, to feel as if they have gained a sense of control.

Even though many readers will be unfamiliar with how to read Norwegian, or even how it sounds, this bilingual edition allows one to see the source of “My mother’s mother-of-pearl,” which reads as follows: “Min mors perlemorknapp” (10). Wadlinger, in her translation, maintains the several m-sounds in that line. On the whole, she displays throughout the book an astute ear for the sonic elements within Dahle’s work, and skillfully renders English-language poems. One of the pleasures of bilingual editions for readers, particularly when one isn’t familiar with the language being translated from, is looking at the originals and translations as (mirror) images, not to compare for visual accuracy, but simply to see what shapes the translator had to work with, and what types of decisions she might have had to make about the visual presentation of the work. In Wadlinger’s case, she seems to have replicated the finely honed shapes of Dahle’s originals. As I move from one poem to the next, my eyes feel the pleasure of carrying the shadow-image of the Norwegian into the English.

A Hundred Thousand Hours is Dahle’s first appearance in English, as well as Wadlinger’s first published book of translations. Judging from this work, they are a good pairing, which makes me hope Wadlinger will continue to bring Dahle into English. To everyone’s advantage, though, the translator will not need to rely on chance, at least not as much as she did the first time around when she waded into those stacks in Oslo. Perhaps Wadlinger, by now, has also been tipped off to other Norwegian works that would help readers to develop a stronger sense of Dahle’s generation of writers, a generation that includes the bestselling crime novelist Jo Nesbø. Norway’s iconoclastic literary tradition is too little known here in the United States. Prior to Nesbø’s international success, Henrik Ibsen and Knut Hamsun are most likely the only other Norwegian writers with name recognition for American readers. Judging from this short, but male-dominated, list, we could certainly benefit from becoming more aware of women’s writing in Norway. Rebecca Wadlinger, with her translation of A Hundred Thousand Hours, has provided readers the necessary introduction.

1. Anna Clark, “You’re Missing Out on Great Literature,” Pacific-Standard, February 11, 2014.

3. Hannah Withers, “Translating Immediacy and Manic Delight: A Micro-Interview with Rebecca Wadlinger,” May 20, 2011.