'Reader, we were meant to touch'

On Erica Hunt's 'Jump the Clock: New and Selected Poems'

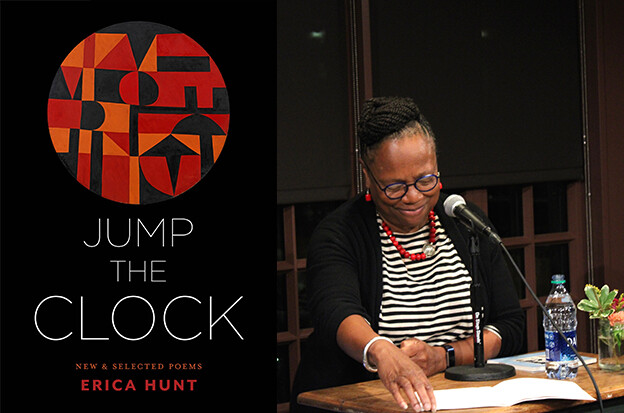

Jump the Clock: New and Selected Poems

Jump the Clock: New and Selected Poems

Erica Hunt’s Jump the Clock: New and Selected Poems (Nightboat, 2020) gathers six revised full-length collections and chapbooks. Across their nearly thirty years of publication, edited in and with the present, they propose ways of reconceptualizing time that work against a ground of racial capitalist marginalization to generate radiant clarity about the conditions of our living. They are specific, often, about how time feels — how various pasts feel in the present, and how language makes evident the variability of what time is and how it behaves. Hunt’s poems exemplify how we can use language to form new relationships to time, and subsequently, to our perception of ourselves as subjects in time. In the poems, these relationships are the engine at once of resistance and of hope.

For Hunt, collective and individual apprehensions of time cannot be disentangled from social and political rhetorics that rehearse destructive power dynamics: “Tricks of narrative,” she writes in “Home,” “join sections of fixed action to the next action.”[1] The line “the past is imperfect; it is unfinished” first appears as the epigraph to the poem “Time Slips Right Before the Eyes” (133), and is repeated, in variation, throughout the second half of the collection. This repeated line recognizes our capacity to redirect the precarious potentials of the present toward future possibilities that a narrow view of the past would have foreclosed.

The remaking of time is foregrounded by the collection’s title, Jump the Clock, which suggests at once to restart time, jumping a clock as you might jump a dead car battery, and to enter into kinship made of time, as in the African American wedding tradition of jumping a broom. The phrase “jump the clock” as it appears in the poem “Octavio Paz’s Calendar” reminds us that the opportunity to reimagine a relationship to time is a privilege of being and staying alive. As Hunt writes, “Not everyone lives to jump the / clock” (117).

The refusal of time as always already concretized and cumulative is a refusal of what Hunt calls “the master narratives” in her 1990 field-shaping essay “Notes for an Oppositional Poetics.” In the essay, Hunt presents poetics as a framework through which we can engage with the structural ways dominant ideology is embedded in the fabric of language itself, intricately threaded throughout literature, and ingrained in our speech without detection of its external origin. “How what they say about you make it / say itself through you / its / thought bubbles overheard / closed captioned in your own voice,” she writes in the excerpted section of the poem “A Handbook of Quarrels”: “at the end of that line is that a noose or a question mark?” (115). To disrupt conventional poetic form is to also disrupt representations and experiences of time as linear and predictable at the microscale of the line or the stanza.

In absence of what can be anticipated, the poem manufactures an active space of improvisational thinking wherein new possibilities for being might manifest. In the author’s note, Hunt reflects on this collection as a poetics of the present, and describes poems as “immanent artifact[s]” (193). Within this singular phrase, timeframes that linear thinking would keep discrete compound together at the site of the poem. At once an anticipated emergence still in flux and tangible evidence of what has already come to be, Hunt articulates the poem as a microcosm of the present, an active hotbed of word material churning our languaged visions of ourselves to its bubbling surface. As she writes in “Reader We Were Meant to Meet” of the encounter between reader and writer in the manufactured present of the poem:

Touch, reader, we were meant to touch

to exchange definitions and feed the pulse of

language. I promise if you step in

it will propel you, me, it:

topple distinctions

ease doubt and belief, and

all that in between. (109)

What connects oppositional poetry or poetics and the kind of radical action that Hunt is invested in (evidenced, in part, by her having been a community advocate and organizer for several decades) is that the distinctions toppled in the here of the poem might serve as a rehearsal for dismantling social and political hierarchies that attempt to categorize us and govern our actual living. Aware that “what we do not dream we cannot manufacture” (190), the imaginative labor performed by and in the space of the poem anticipates in language what must be carried out in practice.

Specifically, Hunt’s poems disrupt conventional form to make new language for how time is reworked by environmental disaster, mass production and product testing, anti-Black police violence, and speculative family history and diasporic kinship in the wake of chattel slavery. The poems revisit the scenes of disaster and violence to find in the fragments of their language the ingredients of solidarity and perseverance. They respond at once to pervasive and uneven environmental and social threats and to the linear temporalities and rhetorics of accumulation inextricable from the material context in which they operate.

In Local History (1993), the poem “City” opens:

One lives inside the replica of a city materializing from the sum of its inhabitants’ aspirations, fluctuating on a dial of pluses and minuses. The replica city commands a momentum separate from the city for which one has bought a ticket. The real city swallows the evidence of your arrival, while in the other, where exemplary forgeries abound, it is difficult to read the intention that launched you here, as the words themselves, now realized, dry in their new positions. (18)

Words in “City” become space as they dry into architecture. The place where urban residents live, Hunt articulates, is composed at the meeting of desire and the built environment. To talk about a place, the poem argues, is to talk about the desire that swirls within it. But swirls of desire disagree about what to call the place they occupy, and about how to slot that place into a relationship with past and present. Language is an architectural tool for Hunt, revealing that physical spaces are inextricable both from the ideas of time to which they belong and from the language used to imagine and describe them.

Precision, in an Erica Hunt poem, is a project of articulating where dueling accuracies disagree. Hunt’s poems expose the explicit or implicit attention to how systems of colonial and racial violence delineate the ground of perception on which each accuracy is constructed. Those accuracies are not only composed of perceptions whose aperture is determined by racial capitalism, but also of where those perceptions meet physical realities — in the weather, in geography, in fragmented and unevenly silenced archival and family history.

Hunt’s poems routinely question accuracy by sharpening focus on setting or background, whether that’s the weather or what Christina Sharpe refers to as the Weather, or the “total climate” that “registers and produces the conventions of anti-Blackness in the present and into the future.”[2] As Sharpe suggests, a perception of environmental conditions is inseparable from the atmospheric conditions of anti-Blackness. Hunt uses her poems to critique how capitalism unevenly fails almost everyone who operates within it.

In “Veronica,”Hunt confronts how the ubiquity of anti-Blackness under the conditions of capitalism produces failures of precision through public acts of naming that smear Black people, and Black women especially, together as an undifferentiated receptacle for dehumanizing, discursive harm:

We’d always paid attention (what price, what loss?)

but randomly assigned names. For instance, someone

mistook Veronica for me, as if our names were

interchangeable syllabically, for Black, female,

fat, thin, poetic, shy and angry, unpredictably

angry, closets filled with mysterious anger

coming from nowhere to erupt

anywhere (158)

Black feminist scholar Hortense Spillers describes the application of these kinds of “overdetermined nominative properties” as the rhetorical remnants of the colonial and plantation logics that transformed humans into objects, people into property.[3] The parenthetical question, “what price, what loss?” foregrounds and interrogates the value-based thinking that undergirds this mode of misrecognition.

At the same time, Hunt’s poems are interested in what it means to resist in capitalism’s anti-Black Weather, to desire within the terms of capitalist exploitation while also refusing those terms. They register that interest by turning their critical aperture on their speaker. In the poem “Correspondence Theory” she writes,

I too have a confession to make. While I accuse you of not being yourself, I myself am contrary. When my habits are pointed out to me I deny the fit. Facsimiles make me itch. (44)

“Correspondence” in the poem is a series of letters, a correspondence between two people of which the reader is only offered one side. But “correspondence” in the poems is also a question of agreement, of how to desire at once out from and under capitalism, of how to have and make a quotidian life in decades of anticipating disaster, of how to twist rhetorics of power into their own anticapitalist critique, and to reflect their focus not only outward but back on their author.

In other poems, Hunt highlights moments of internalized misrecognition as a strategy for the normalization of systems of racial capitalism, as in “the voice of no,” which appears in the 1996 collection Arcade. The poem opens, “No need to be contrary, I put on a face.” It ends with another scene of disaster, perhaps a hurricane and certainly some kind of flood:

and anyway

rescue is sure to be slow.

In place of a raft

we paddle

ladders past the litter of drifting bodies” (89).

In “the voice of no,” the speaker’s attachment to a reliable quotidian, a daily life in which things have the privilege of feeling ordinary, is a smokescreen for disaster. Across Jump the Clock, Hunt is certainly interested in uneven and various experiences of daily life in the US of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, as well as its gendered and racialized conditions and how it is reinforced by the object world of mass production. But she’s also suspicious of finding a kind of comfort in a quotidian that flattens complexity or makes opposites of dailiness and urgency, such that her own poems would functionally disappear. In another early line in the poem, she writes, “No need to read, 24 hours of the shopping channel” (89).

Her turns to contrariness recall education scholar Eve Tuck’s encouragement to think with what she terms a “desire-based framework,” through which critics of racial capitalism might nuance their own embeddedness within it. As Tuck reflects, “in a desire-based framework that draws on the idea of complex personhood, we see that ‘all people remember and forget, are beset by contradiction, and recognize and misrecognize themselves and others.’”[4]

For some of us against whom the English language in particular has been leveraged to riddle us out of recognition as human beings and to arrange us as the bottom of racial, gendered, and classed hierarchies, the dismantling of the line or even the word is a discursive reflection of disassembling the language of “democracy” and global capital that demands the dispossession of some for the benefit others. In “Broken English” Hunt writes, “wound up in words / wounded / re-wounded / the beaten/ bulleted body / repeats / wound / reads / into ache” (173). From the same and most recently released collection, Veronica: A Suite in X Parts, published in 2019 as an extended meditation on grief in the immediate wake of state-sanctioned murders of Black people by the police, one poem entitled “‘Someone matching your description’” takes to task the uneven ways in which language adheres to body and flesh according to deathly consolidations of power:

I wonder

who wrestles with me

or you (even)

to argue “reasonable doubt”

when I know they never leave their

guns

they carry them

in churches, bars and court rooms and put

“scare” quotes around the world

they

are never mistaken

there are no words for mistake

no words

for mistake (153)

The chasm between me and you, I and they, is a site of both friction and slippage. It is the measure of that distance that Hunt troubles and traces, insistent on the urgency of attending to the conditions of our interdependence while living in this era of material mayhem, global ecological catastrophe, and sweeping racial and gender-based violence.

“We were in narrowed straits” (emphasis our own), she observes later in “Veronica” before inquiring, “how narrow, how straitened?” (157). The we that is pressed and strained and which struggles to adhere in the narrow straits between me and you, I and they, is a vehicle for creating other social arrangements that could dismantle the modes of illegibility that create such uneven and unlivable lives.

Still, even as Hunt strives for the we, its formation is not valorized without critical attention. As she writes in “Sorrow Songs,”

We who oppose—

(who is this we?) (178)

While the orientation of opposition is important, the conditions of the arrangement of the we inform what is opposed, why it’s opposed, and how it’s opposed. A central focus across Hunt’s collections is her exploration of the tonal nuance of even those smallest words that we use to draw lines of connectivity between us — I, me, you, they, we — and how those lines are shaped and then shifted, necessarily and iteratively over time.

Across the collections in Jump the Clock, Hunt’s poems demonstrate that the rhetorics of connectivity contain within them the possibility of hope. As W. E. B. Du Bois writes in The Souls of Black Folk in his discussion of what he terms “Sorrow Songs” sung by Black enslaved people and their descendants, “Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope — a faith in the ultimate justice of things.”[5]

Throughout the nearly thirty-year arc of Jump the Clock, the primary struggle is with the language of domination and its relationships to time. How, Hunt’s poems ask, can we constitute selfhood that opposes a language of domination from which it cannot be fully separated? How can the exercise of demonstrating how language about space and time encodes ideas of race and gender itself be a practice of resistance?

Part of that answer lies in sharpening our sense of relation and strengthening networks of solidarity and mutual support to counter the overrepresentation of the individual as an isolated consumer, singular owner, or overruling gatekeeper. The choice to be accountable to one another, to act on one another’s behalf out of an intentional recognition of our inherent interdependence, fashions care as a method for survival. The choice must be autonomous and made in the face of conditions aimed to do more than divide. In the final two stanzas of “Veronica,” Hunt writes, “we were ready to turn on / each other the fire hose of free floating ire / but for this— / we exchanged our hands over our hearts / hers for mine and mine for hers.” (160)

This exchange of one’s hands over another’s heart describes an embodiment that signals the kind of working love ethic that is this collection’s north star.[6] Immediately following the terse, dystopian last two lines of the poem “Fr**dom,” “Nothing left to be broken / Nothing left to be taken,” comes the title that repeats across two books in the collection, “This Is Where Love Comes In” (186). In the clearing of profound grief and loss, love, for Hunt, becomes an ethic and a guide, an inspiration and a call to labor towards, for, and with one another, as unembellished as lacing one’s shoes and getting out of the door when all other faculties are calling you to hesitate or hide. “There’s so much to do for justice, we’re running out of brink,” she writes in “Love”; “I grab my socks and pull them up. Slip the latch on my one-track mind and avoid the chair that catches me with a nap” (187). With a hand over her heart, Hunt leads us by love deeper into our attention to the present, wherein past and future teeter on our tongues, waiting to see just what we are really ready to do.

1. Erica Hunt, Jump the Clock: New and Selected Poems (New York: Nightboat Books, 2020), 134.

2. Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 21.

3. Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 64–81.

4. Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 4, quoted in Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3, (Fall 2009). 409–28.

5. W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015), 197.

6. In the short piece “Love is a Growing Up,” Hunt describes James Baldwin’s writing, especially on justice and love, is “as critical as the North Star” to her writing practice.