Poetry/painting/history/hermeneutics

On 'Cy Twombly: Making Past Present'

Cy Twombly: Making Past Present

Cy Twombly: Making Past Present

Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. — Susan Sontag, “Against Interpretation”[1]

This sentence from Susan Sontag has been knocking around in my head for probably thirty years. And I still don’t know if I agree or disagree with it. The poet side of my brain intuits that Sontag is correct: content is illusory, along with the myth of authorial intent. As artists, we do not know what we are doing. We are just trying to make a thing and create an experience. I’m not sure our work contains anything. But the scholarly part of my brain, which is also the part that teaches other humans, and that lives in twenty-first-century America, is persuaded by the notion of content, especially in texts that are not officially “art,” like a note from my son’s teacher, a president’s comments during a speech, a recipe for chili, a comment on Twitter, a flyer in my local coffee shop about Breonna Taylor, or a message from the Center for Disease Control. The question is, why let art off the interpretive hook? Or, put another way, who gets to decide what is interpretation and what is engagement? What if interpretation is a form of celebration? What if interpretation is always already a mode of creation?

For the past several years, these questions and many others have come to dominate my daily thinking as I have been deeply mired in the work of Cy Twombly (1928–2011), a revolutionary artist about whom the question of content continues to swirl. Twombly is often aligned with fellow Black Mountain alumni Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, though Twombly’s work is more gestural and less taken with photography and found objects. In short, Twombly is less graphic and more calligraphic. Considered an abstract artist who came after abstract expressionism, but who was neither a pop artist nor a minimalist, Twombly is best known either for his large canvases that contain little more than a series of circular scrawls that resemble an unending line of cursive e’s or for his drawings that are interplays of image and text. Frequently, his “pictures” feature scribbled lines of poetry by poets like John Keats, Sappho, Federico García Lorca, Stephane Mallarmé, and Rainer Maria Rilke. These pieces require double decoding of both “drawing” and “writing” — and ask, subtly, if there is even a difference between the two.

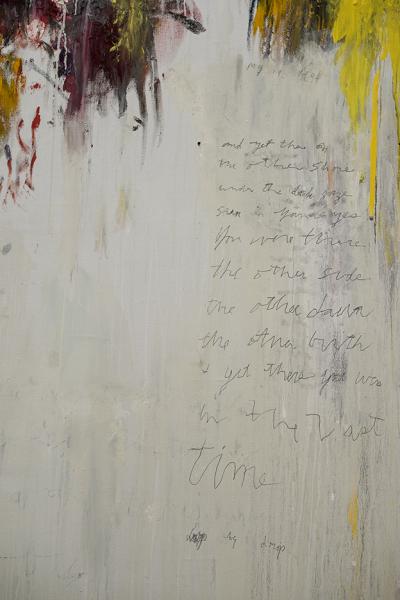

For me, that tension between poetry, writing, and drawing is utterly captivating. So much so that I have spent the last two years writing poems that enter into conversations with Twombly’s work, a project I have found both humbling and transformative. In fact, the last real public outing I engaged in before the pandemic lockdown was a visit to the Cy Twombly Gallery at the Menil Collection in Houston. I spent an entire afternoon going in and out of the rooms, always finding myself standing, speechless, in front of Twombly’s epic elegy, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), with its enormous panels, huge splotches of color, skeletal boats, and scratched lines from Rilke. I could not have predicted what our planet was about to endure, but I did have the sense I was staring into a threnody, not just for the past but also the future.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, To the Shores of Asia Minor), 1994, oil, acrylic, oil stick, crayon, and graphite on three canvases, 157½ × 624" (400.1 × 1585 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist. Photographer: Paul Hester. © Menil Foundation, Inc.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, To the Shores of Asia Minor), 1994, oil, acrylic, oil stick, crayon, and graphite on three canvases, 157½ × 624" (400.1 × 1585 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist. Photographer: Paul Hester. © Menil Foundation, Inc.

As both a writer and a human, I would like to recreate for readers the experience of standing in that borderless space of Twombly’s canvas, to help readers see what I saw and feel what I felt. But to do so would require me to endure the humiliation of “description,” which is, at its core, also an act of interpretation. It is also a concession to content I am not ready to make. One reason I turned to writing poems about Twombly’s work is because discursive options came up short. They fell flat. They slept when Twombly’s drawings soared. After all, how does one depict motion? How does one portray energy? How would one describe something as ineffable as Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor)?

Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, To the Shores of Asia Minor) (detail), 1994, oil, acrylic, oil stick, crayon, and graphite on three canvases, 157½ × 624" (400.1 × 1585 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist. Photographer: Paul Hester. © Menil Foundation, Inc.

As soon as you attempt, you fail. Description is reduction, and reduction is the antithesis of art. Or, if reduction is not the antithesis of art, it is its crude copy, its police sketch. So, we resort to a different mode of reduction — a reproduced image. But even though it serves a purpose, such a stand-in pales in comparison (what Derrida would call a “nondisposable double”). This, of course, is the thesis of Walter Benjamin’s canonical “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art,” writes Benjamin, “is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”[2] Perhaps you are experiencing this right now: you are “seeing” a photo of a painting, but you are not seeing the painting.

Luckily, reproducing a poem on a page is less fraught with auratic diminishment than reproducing a painting. In fact, it just might augment it.

Twombly understood this.

&

Twombly also understood the second part of Benjamin’s observation about aura: “This unique existence of the work of art determined the history to which it was subject throughout the time of its existence.”[3] Benjamin is thinking of history not as an eternal picture of the past, but as discreet events always open to interpretation, a perspective (intentional word choice) Twombly would find comfort in. And so, I would like to use that notion of history as a pivot to better consider the eccentric and lovely Cy Twombly: Making Past Present, an exhibition catalog for an exhibit yet to occur.

I shall explain.

In 2020, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts was slated to host an exhibit that contextualized a selection of Twombly’s work alongside sculptures and other artifacts from classical antiquity, including some items from Twombly’s own collection. However, the pandemic forced the museum to close and the exhibit to be postponed. In the meantime, the MFA (where Twombly studied) issued this catalog that now functions as a kind of preview of the forthcoming exhibit. Generously illustrated, lovingly assembled, and masterfully designed, Cy Twombly: Making Past Present is the most interesting book on Twombly to emerge since Reading Cy Twombly: Poetry in Paint by the literary scholar Mary Jacobus. In this catalog, Jacobus, along with five others, lay out various reasons why it is important to read Twombly, an artist whose aesthetics feel utterly contemporary, against the backdrop of antiquity. Indeed, the basic premise of the book is that the richest source material of Twombly’s art, even his abstractions, is to be found among texts, images, and artifacts of the ancient world. As Jennifer Gross argues in her essay on Twombly’s sculpture: “[Twombly’s] attraction to white paint, cultural fragments, and cast-off materials were innate aesthetic proclivities. Though he brought these inclinations to the table as an artist in the United States, antiquity was the culture that nourished them and caused him to flourish.”[4] That notion of flourishing animates each essay in part because the authors draw on their various expertise to demonstrate the degree to which Twombly’s fascination with ancient Greece and Rome was a catalyst for his art.

While the catalog’s audience is clearly the art world, one of its surprises is that it has a great deal to offer literary scholars and the world of poetry. In fact, upon close reading of the essays, what emerges (perhaps by accident) is that the major antique inspirations for Twombly are not necessarily art and artist but history and poetry — in particular, the metaphorics of history as refracted through the lens of poets and poems.

&

Of course, the chapters are replete with reproductions of antique accoutrement like columns and busts and torsos and jars and vases as a way to give a visual reference to Twombly’s works. However, the authors always come back to the poetry. Jacobus, along with the fabulous poet Anne Carson and the brilliant classics scholar Brooke Holmes, offer smart, insightful readings of Twombly’s poetic groundings, solidifying the book’s literary bona fides. The other essays are written by curators and art historians but ultimately wind up relying on poetry and poetic citations ranging from Homer to Keats to Virgil to C. P. Cavafy to Charles Olson to Johan Wolfgang von Goethe.

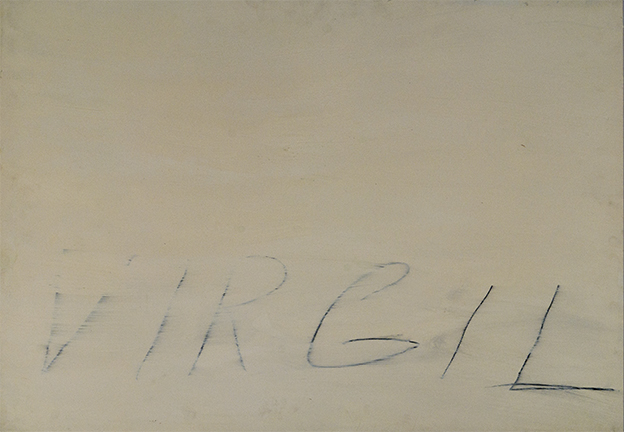

Christine Kondoleon pens two essays, one of which functions as a sort of introduction to the entire project, titled “Encountering the Ancient World.” Here, Kondoleon, a noted curator of antiquities at the Boston MFA, establishes the degree to which Twombly’s work and life were ensconced in the literature, history, and art of ancient Greece and Italy. In 1952, after stints at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, New York’s Art Students League, and Black Mountain College (where he worked with Robert Motherwell and befriended Charles Olson), Twombly made his maiden voyage to Italy, and by 1959, he had moved there. For the rest of his life, Twombly’s primary residence was Italy. Kondoleon’s essay not only traces these paths but also chronicles Twombly’s journey as a collector, citing both Rauschenberg and Dominique de Menil’s accounts of Twombly’s insatiable interest in ancient artifacts, regardless of condition or value. In fact, Twombly preferred the worn and damaged. “One can speculate,” writes Kondoleon, “that he was drawn to the patina of age and to the process of deterioration of objects long buried” (18). I see this affinity toward effacement in Twombly’s proclivity for erasure as in this drawing? Painting? Etching? (what is the correct noun?) of Virgil’s nominee:

Cy Twombly, Virgil, oil paint and graphite on paper, 1973, oil paint and graphite on paper, 27 3/8 × 391/16" (203.8 × 132.4 cm). Photographer: Belisario Manicone. Courtesy Cy Twombly Foundation, © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Cy Twombly, Virgil, oil paint and graphite on paper, 1973, oil paint and graphite on paper, 27 3/8 × 391/16" (203.8 × 132.4 cm). Photographer: Belisario Manicone. Courtesy Cy Twombly Foundation, © Cy Twombly Foundation.

The wisps of white paint whisked horizontal across the letters endow the drawing with a windblown appearance. It is as though the name itself cannot hold up to time’s erosive powers, the letters worn away like the nose from a bust of the poet himself.

And yet, I am never sure if the great poet’s name is about to be revealed or about to be erased — a paradox I realize I have come to feel about pretty much all of Twombly’s oeuvre.

In her longer, more theoretical essay, “Color and Line, Gods and Poetry,” Kondoleon sets up a conversation between sepulchral tablets, various busts and casts of armor, and Twombly’s work, such as Virgil and other text-heavy drawings that are nothing more than the names of famous figures like Apollo and Venus and Thrysis and Dithyrambus. In one of the best moments of the book, she patiently decodes the canonical Six Latin Writers and Poets and Five Greek Poets and a Philosopher, multipaneled works each bearing the emblazoned name of one famous figure, like Tacitus, Homer, and Sappho. Executed in dark pencil or crayon, sometimes in cursive, sometimes in all caps, the pieces are composed of nothing more than an off-white background and the name of the writer, always presented in that shaky Twombly hand that suggests age or uncertainty or near-illiteracy or all of the above. Kondeleon correctly notes that “the writing of texts in pencil is key to Twombly’s innovation of introducing language into painting,” but she goes on to argue that these pieces, when placed together, serve much the same purpose as the ancient Greek and Roman practice of lining up busts of famous men (36). I found myself wondering how reading the name “Catullus” was similar or different than looking at a bust of “Catullus.” What acts of visual decoding go into both?

Semiotics. Signifiers. Signifieds. Language. Drawing. Writing.

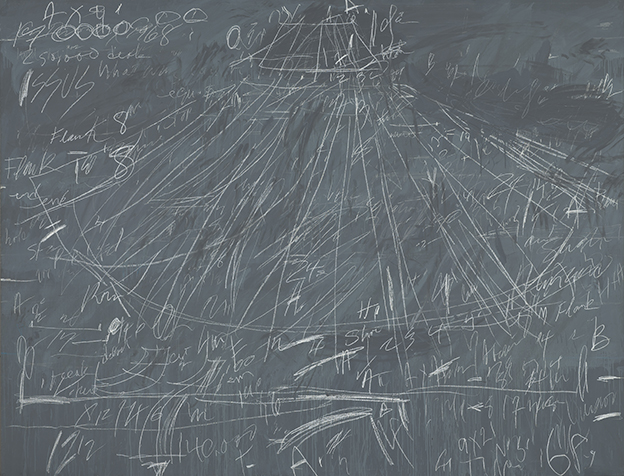

Kondoleon’s essay is a great opening salvo for the interpenetration of Twombly and the ancient world. It also gets the best art. It’s good to be the curator! There is a gorgeous four-page reproduction of Twombly’s Roman Notes that spans both verso and recto as well as two of my favorite Twomblys: Mars and the Artist on an entire page and the awe-inspiring Synopsis of a Battle complete with a full verso and recto detail.

Cy Twombly, Synopsis of a Battle, 1968, commercial oil-based paint, wax crayon on canvas, 79 × 103⅛" (200.66 × 261.94 cm), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Sydney and Frances Lewis, 85.451. © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Cy Twombly, Synopsis of a Battle, 1968, commercial oil-based paint, wax crayon on canvas, 79 × 103⅛" (200.66 × 261.94 cm), Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Sydney and Frances Lewis, 85.451. © Cy Twombly Foundation.

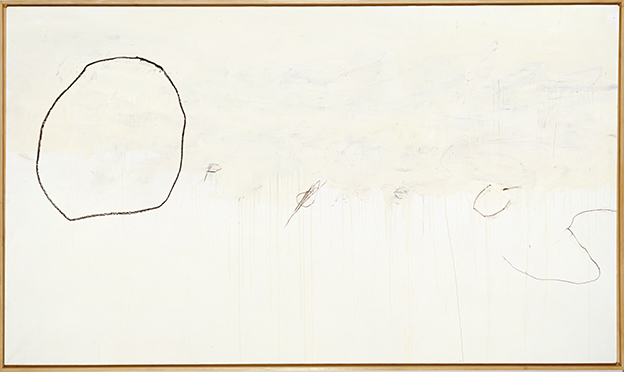

As much as I love the art in Kondoleon’s chapter, I found myself jealous of Mary Jacobus’s “Akephalos/The Headless One” because she gets to talk about Rilke. When it comes to Rilke, Twombly and I enjoy a shared obsession. At least, I enjoy sharing an obsession with Twombly. Jacobus uses Rilke’s, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” as a launchpad to discuss the importance of the Apollonian motif in Twombly’s work, but also how Twombly found affinity in other writers for whom Italian and Greek poetry was central, like Rilke, Goethe, and Cafavy. I would add to this list the poet John Keats, whom Jacobus overlooks but whom Twombly adored. Jacobus is at her best when she dramatizes the rather remarkable triumvirate of Twombly/Rilke/the ancient world. She traces this connection through Rilke’s poem “Leda and the Swan” and Twombly’s paintings of the same name, but most convincingly through the figure of Orpheus, whom Rilke and Twombly seemed utterly transfixed by. Rilke’s 1923 collection Sonnets to Orpheus mixes spiritual yearning and lyric compression. Twombly’s many Orpheus drawings and paintings feel like homages not just to the idea of Orpheus, often considered the first poet, but to poetry itself, perhaps manifested in Rilke. Jacobus: “Twombly scatters the letters of Orpheus’s name across canvas or page in a sparagmos (alphabetic dislimning) that emphasizes the lyric ‘O’ of song” (96). Sparagmos in Greek means to rip or rend, to tear apart, a la Dionysus. The rent or missing head of Apollo finds resonance in the erased Virgil, the missing nose, the fragments of poetry partially legible on the page/canvas/paper.

To my eye, Twombly treats the name of “Orpheus” differently than that of “Homer” or “Virgil” or “Catullus.” Granted, Orpheus is mythical, but he is also Rilked. Poets are lenses for Twombly, and he tends to be moved by those figures who have been figured by another poet — way more than by another artist. And no one gets more of his attention than Rilke and Orpheus. Here it is as though the canvas is not expansive enough to contain Orpheus’s essence. He goes outside the margins, beyond the knowable.

Cy Twombly, Orpheus, 1979, oil-based house paint, paint stick, and wax crayon on canvas, 77 × 1313/4" (195.7 × 334.5 cm). © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Cy Twombly, Orpheus, 1979, oil-based house paint, paint stick, and wax crayon on canvas, 77 × 1313/4" (195.7 × 334.5 cm). © Cy Twombly Foundation.

The three middle chapters take different tacks but all have the same goal — situating the artist in the ancient world and positioning some aspect of his art within that context. Kate Nesin’s erudite, convincing essay examines the notion of place in Twombly’s drawings, paintings, and sculpture. She takes a cue from Roland Barthes, who, in his famous essay on Twombly, warns viewers not to take Twombly’s titles (on the rare occasion he provides them) too literally. Twombly did not always title his paintings, but he often included the city or place where he executed them — like Rome, New York City, Gaeta, Bassano, Bolsena — as though setting could function as proxy for the title. Consequently, Nesin is interested in what “landscape” might mean in a Twombly picture, what his notion of representation might tell us about him, a place, an idea, language. But, she finds Twombly frustrates facile forms of interpretation. Ultimately, she sides with Barthes admitting that when it comes to writing about Twombly, “language seems inadequate” (158) (as the many shortcomings of the essay you are currently reading evince).

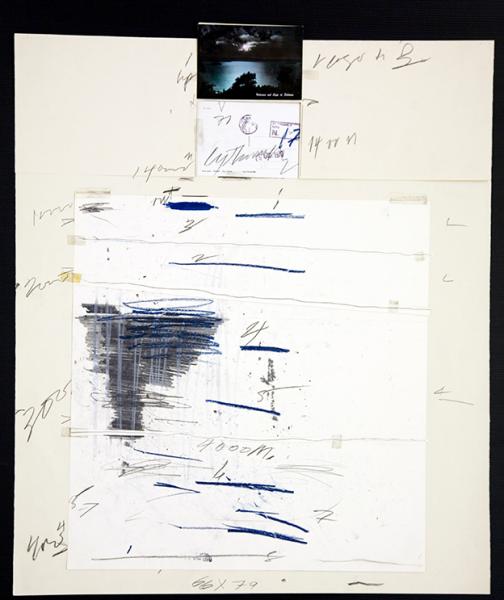

Jennifer R. Gross’s “A Return to Sculpture” is, for me, the most surprising contribution of the collection not because she places Twombly’s sculptures in dialogue with pieces from antiquity, but because she considers Twombly’s collages, which I have always found criminally underappreciated. For Gross, Twombly the sculptor and Twombly the collagist attempt, dually, to channel ancient culture into a contemporary idiom. In the late ’60s, Twombly revisited Leonardo da Vinci (there is compelling evidence Twombly’s iconic cursive scrawls were influenced by Leonardo’s deluge drawings). In Leonardo’s renderings of flowing water, Twombly saw something sculptural, and it led him to collage. Twombly would take postcards of landscapes and place them vertically on paper, sometimes in linear stacks. Other times, he would arrange the card to make it appear it sat atop a plinth.

Painting on pedestal, pedestal on page, page on a wall; page in a book.

I have long thought these collages strike an appealing balance between his abstract drawings and his three-dimensional sculptures. Because he incorporates photographs of landscapes, an unusual element is introduced into a Twombly plane — mimesis. Surrounding the photographs, one finds typical Twomblyisms, but the effect is sometimes jarring, as though an alien species has been introduced to the field. A fascinating project. According to Gross, these collages were an “attempt to introduce a sculptural space into the image field,” an insightful reading. But I also suspect they were an attempt to create a page, something bookish, as in Untitled below.

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1970, postcards, drawing paper, transparent adhesive tape, graphite, wax crayon, and ink on paper, 311/8 × 26" (79.06 × 66.04 cm). Courtesy Cy Twombly Foundation, © Cy Twombly Foundation.

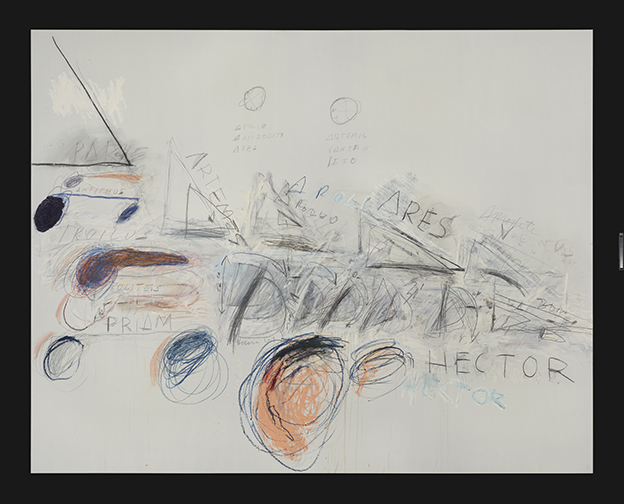

Brooke Holmes’s wonderful “The Time of Achilles” shows just how bookish Twombly was, by looking closely at his stunning Fifty Days at Iliam, a ten-panel work in response to the Iliad. She begins with a series of questions into what we, as scholars, writers, and critics, are really to make of Twombly’s fascination with ancient Greece and Rome. Is it inspiration or play or erudition or escapism? I have often wondered if Twombly’s devotion to antiquity was a kind of elitism (ultimately a mix of all of these concepts). But Holmes craftily refrains from any hard and clear verdict. What she does instead is walk us through how Twombly, a la Nietzsche, produces “an intervention with the present capable of resisting both the stultifying timelessness of classicism and the myopia of presentism” (209). That is perfectly put, and for me is the clearest articulation of the exhibition and the book’s ambition.

Cy Twombly, Fifty Days at Iliam: Ilians in Battle, 1978, oil paint, oil crayon, and graphite on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift (by exchange) of Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, 1989, 1989-90-8. © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Cy Twombly, Fifty Days at Iliam: Ilians in Battle, 1978, oil paint, oil crayon, and graphite on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift (by exchange) of Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, 1989, 1989-90-8. © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Fifty Days at Iliam is a remarkable work. Intense and immersive, blurry and bloody, sexual and textual. Having been fascinated by it for years, I have written two different poems in response to this work, including a ten-panel crown that corresponds to each of the panels. My goal was to accomplish linguistically what Twombly executes visually.

I failed.

But so too does Twombly fail to unhinge Homer. However, reading Homer through the lens of Twombly makes the poet more lyrical, more prophetic than he might otherwise be; just as reading Twombly through the lens of Homer makes the artist palpably more epic. One of the missed arguments this book could have made is how one might read Twombly’s oeuvre as a kind of epic poem, with the artist himself as the epic hero, Odysseus-like, Dante-like, descending into the underworld of the self before emerging to the glory of expression. It is not a given but not a stretch either.

If I am interested in Twombly or Homer as a lens, Anne Carson is interested in Catullus as a lens. Her short but cagey “A Rustle of Catullus” offers a path into Twombly’s painterly poetics by way of the beguiling Latin poet. Catullus was caught, like a hook in a fish, with ancient poetry. He translated Sappho into Latin and tried to render Greek meters into the Latin phonetical system. According to Carson, Catullus “changed the diction of lyric verse, admitting words like lotum (piss) and defututa (‘fucked to bits’). He changed the whole velocity of the poetic task of telling it like it is, whatever it is — he speeded up the surface” (229).

Sounds like Twombly.

For Carson, Twombly and Catullus are spiritual brothers because they willingly dive equally into the deep pools of eros and thanatos, or as she puts it, “mingle together exposure and erasure” (230). I agree that Catullus and Twombly make for a brilliant pairing, in part because I see Catullus’s work as a translator akin to Twombly’s. To me, he translates the lexical field into the visual field. The phonetical is transformed into the spatial. Neither is interested in mere representation. In the painting I first mention above, Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), Twombly refigures and even rewrites Catullus, just as he translates and transmogrifies Rilke. Carson ends with a quote from Twombly that perhaps has been the not-so-secret subtext of the whole project all along: “Ancient things are new things.”

&

I would like to return to Benjamin and history as a way of making one final observation about Twombly and the past, which I know is not technically the same as “history”; however, they are two sides of the same drachma. Early in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Benjamin writes, “To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was’ (Ranke). It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.”[5] According to Benjamin, history should not be viewed as a linear progression of events, each leading to another, but rather as isolated moments always open for interpretation and, dare I say it, illustration. He goes on: “In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it.” To me, Twombly’s interest in history is less an endorsement of elitism or colonialism or classicism but is instead a resistance to how easy iterations of these terms tend to reify the aesthetic project (or [a la Benjamin] the historical project). Thus, Twombly’s visual “articulations” of history are not mimetic modes of nostalgia for a gloried past or a storied tradition, but an interrogation of nonsubjective, nonpoetic enactments of what we have come to think of as THE past. His chaotic renderings, his aesthetic maelstroms, his thrashes and scratches, are the very “flashes” of which Benjamin speaks. But just that — flashes, glimpses, images. What if the perception of the past is primarily visual?

Twombly tends to be attracted to writers, to texts. Thus, his interest in “the ancient world” as a metanarrative seems valid but not totally on point. To me, Twombly seems more interested in ancient aesthetics, ancient attempts, ancient artfulness in much the same way he is interested in Rilke and Mallarme and Keats and Lorca. He is interested in energy and articulation, the successful and the failed modes of communication. Thus, the real contribution of this catalog might be as a corrective. History is now. The past is present. We are all trying to write it.

&

I lied.

This is my final observation.

I’m not sure readers noticed the names of the authors, but the contributors to this volume are all women. This goes unmentioned in the catalog, but I absolutely love this detail. It seems impossible to imagine a similar catalog on Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol or Donald Judd or Robert Rauschenberg with no male contributors.

And one more: this catalog demonstrates just how wide Twombly’s appeal actually is. On paper, Twombly’s lack of figuration, his documented obsession with old-school texts and writers, his refusal to do interviews or be filmed making his work, his preference for Europe over America, his reluctance to be either totally figural or totally abstract, should make him less available to critics and collectors. But he remains relevant and revered. We love Twombly for the same reasons we love Rilke — he is in it. He gives in to the work, he gives in to the emotion. He dives into the chaos. He becomes the chaos. Like Rilke, he answers both the call of light and the call of darkness. Everything is incident. We love Twombly because we feel him thinking his way through the emotional vortex. Or, we see him seeing his way through his intellectual vortex. Those are projects out of time but always timeless.

Which is to say, maybe the content of Sontag’s epigraph is not “meaning” or “material” or “history” or “poetry” but rather Twombly himself. Maybe he is the content. Inviolable. Immanent. Impossible to interpret.

1. Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York Picador, 2001), 10.

2. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 220.

3. Benjamin, “Work of Art,” 220.

4. Jennifer Gross, “A Return to Sculpture,” in Cy Twombly: Making Past Present, ed. Christine Kondoleon and Kate Nesin (Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts, 2020), 176.

5. Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, 255.