Notes on 'A Mammal of Style'

A Mammal of Style

A Mammal of Style

Let’s begin with the title A Mammal of Style, which of course echoes the Chicago Manual of Style, someone’s notion of the proper and correct way of rendering sensible sentences in the English language. A manual isn’t a book you read, it’s a book you have close at hand — the word means hand, functional and straightforward. This book feels like that.

But a mammal isn’t a manual; it’s an animal. It could be a human animal, but as animals humans have no proper way of doing anything. They do what comes naturally. They live in the world, reacting to it. Grunting and grimacing, as the occasion demands. A mammal of style describes what this book is: grunts and grimaces of literary style, gestures, blunt-force interventions. Distinctly not sensible.

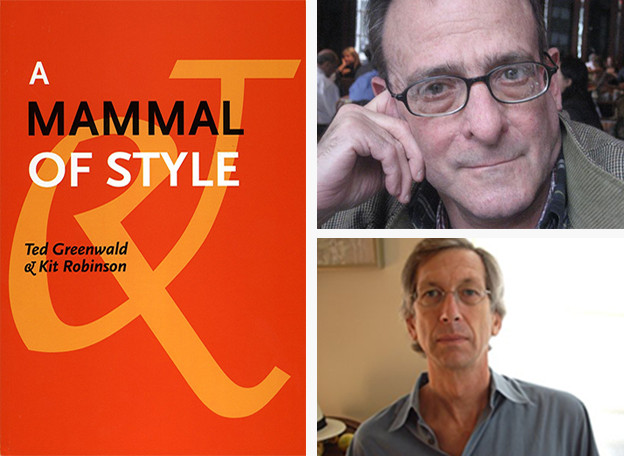

Its collaborative authors, Ted Greenwald and Kit Robinson, have been well known as practitioners of the art of innovative poetry for many decades, both of them, to my ear, having consistently written a poetry that is edgy, flat, and tough, without much ornament, very much in the American idiom, with lots of local slang, technical terms, and contemporary buzz-words, sending up all these vocabularies and simply doing them in a dead-pan, satirical tone — the opposite of passionate or emotional. In fact, decoration, elegance, subtlety, beauty, are not words one would normally use to describe Ted’s or Kit’s writing, as far as I know it. So they are natural colleagues and collaborators. Together they have produced in A Mammal of Style a wonderful source text for anyone who wants to hear a peculiarly trenchant American take on contemporary life and letters. “Kit” and “Ted”: plain three-letter American guy names.

Mammal is a substantial text, more than 130 pages and divided into six distinct sections, each devoted to a different poetic form: sonnet, sestina, haibun, maybe haiku, a three-stanza fifteen line form that might be a version of the medieval French rondeau, and a final one-poem section that seems to be written free form. There are fourteen sonnets, ten fifteen-line poems (the last being ten lines long, not fifteen), twelve sestinas, and twenty-four haibun. It seems that Ted and Kit had a plan. What’s interesting about the plan is that it violates utterly the implied tone or feeling that goes with these traditional forms. A sonnet — even an unconventional sonnet — sounds and feels a particular way, as does a sestina, a haibun, and so on. These poems don’t sound that way at all; in fact, what’s remarkable about them is how they manage, regardless of form, to sound pretty much the same: full of attitude about the contemporary scene, mostly with regard to the language we use every day to confuse ourselves about what’s going on. This is word by word, phrase by phrase poetry, made often without any noticeable sense of intentional connection from part to part, so that a moment by moment reading of the text, without worrying about where the text is going or where it has come from, is a necessity — and will reward the reader.

What haunts me about this work is its most typical rhythmic structure — many stressed syllables one after the other, almost telegraphic. Here, for instance, are some of the titles of the sonnets: “Trickle Comp,” “Lift Hood,” “Lath Talk,” “Mound Co,” “Poles Claw,” “Light Atch,” “Down Own”; many of the lines within the poems (this is true not only in the sonnets, but throughout) echo this very tough and definite stressed phrasing, which for me expresses a radically unsentimental take on the world as it swirls by. A tough, cold eye. As in the sestina “Fire House and Crowded Theater”:

When all is said virtually

Voice drops do whisper

Well-wishers with access

To home range audience

One bare witness

So difficult to believe

Fantasy is ability to believe …

Later verses of this sestina come, by way of the logic of the end rhymes, to lines like:

Got wheelchair access

Cracked up to believe

… illustrating probably the main technique and message of the work — the wisdom of fractured cliche.

As someone conversant with Buddhist literature I was amused by examples of fractured clichés from that tradition, as these lines that play off the Buddhist formula for confession (“all my ancient twisted karma, from beginningless greed, hate and delusion, I now fully avow”):

all my ancient twisted car parts born of green hail and

diffusion I do now secretarially avow.

… and the several lovely fractured quotations from Dogen.

Political commentary appears frequently, built on pop culture references, with easy humor and without the usual angst or bitterness:

Banana Republicans usher usa into twenty-first century

third world. honey i shrunk the people.

as well as plenty of commentary on poetry and its uses, as in this fantasy about the power of the poet to defeat the world with his verse:

Passing through fields of garbage the syntactical

hero pulls the trigger on meant verbiage shoots the object

of his rampant longitude, dead predicate, and rides off into

the archaic, trailing diaphanous interpellations. How the

West Was.

or this marvelous line that more or less captures what poetry used to do and what it does now:

Scratch at vague word moss, places poetry used to go.

Also, the world’s greatest haiku:

Great sweater

Really love the shoes

And the watch!

In short, this is a delightful book, full of the sorts of recognitions that one wants from poetry, but without the annoyances that that sort of experience could produce in less capable hands than those of Ted and Kit.

I haven’t said much here about the mechanics of the collaboration between these two great poets — how did they do this, what was their method of working long distance (Kit in Berkeley, Ted in New York), what were they thinking, what intentions did they have? When I asked them they preferred not to say, seemingly themselves not focused on methodology or documentation of how a poem is made so much as on the accidental and forgotten stumblings and miracles that make poems appear out of our biographical and cultural miasmas. Neither Ted nor Kit works in a university, and neither seems interested (as do the very many poets who teach and profess poetry) in rationalizing and documenting the making of poetry, focusing on questions of methodology and text, context, on the theory that no text stands alone, it comes out of a cultural and historical moment, it comes out of influences, other texts, biographical realities, and so on. True! We must not become too mystical and precious about our poetries! On the other hand, to make poetry into another reasonable cultural production that can be folded into the cultural/commercial mania that rules our world these days is certainly not such a great idea either. Leave it to poets like our Ted and Kit to manage to remain outside all that, to find a way, together to clear some space for thought.

(Note: Takeaway, published by c_L Press in Portland, Oregon, 2013, is a brief companion volume to A Mammal. It’s a forty-four-page text in a small-format, sewn-bound book consisting of poems with a triplet/couplet form. The tone and subject matter is a continuation of what’s found in Mammal).