A note on the visual poetry of Whalen, Grenier, and Lazer

From the beginning of my writing, I have been concerned with (floored by) the fact of a word, or a letter, as a thing, a physical, elemental, thing — and the act of contemplating such a thing. In the late ’60s, I noticed the poems of Aram Saroyan — one word, say, “crickets” — printed repeatedly in a single column, in Courier type, down the page. My first works were less poems or writing per se about something than memorials to the fact of words, that they appear and seem to signify. Three poets who have been over many decades important to me have developed this material aspect of writing considerably: Philip Whalen in his doodle poems, Robert Grenier in his poem scrawls, and Hank Lazer with his shape poems.

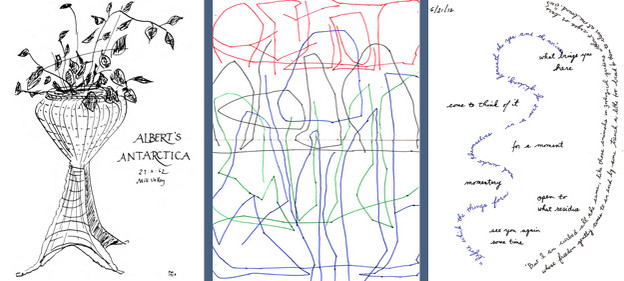

Whalen studied traditional calligraphy with Lloyd Reynolds at Reed College. Accomplished with specially nibbed fountain pens, and written in traditional alphabet styles, such calligraphy is an art form itself, originating in the Middle Ages, for hand-copying sacred texts. Whalen used the pens and the alphabet styles, but was never serious about fully developing his hand — though he did spend many hours, over years, in repetitive practice. An inveterate doodler, he couldn’t help himself from fooling around with pen and ink and paper. Many of his printed poems are doodles of the sort someone might make when talking on the phone or waiting in a doctor’s office, full of curlicues, little drawings, various sizes and styles of lettering. Most of this is lost in the printing, although almost all his books make an attempt to indicate the feeling of the actual notebook page with use of capitals, various sizes and styles of type, etc. Several of his books reproduce pages in facsimile, and there are many such pages in his Collected Poems.[1] Whalen’s original notebooks are available for viewing at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, and Brain Unger is doing a scholarly edition of some of the notebooks.

From 'The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen,' edited by Michael Rothenberg, 2007.

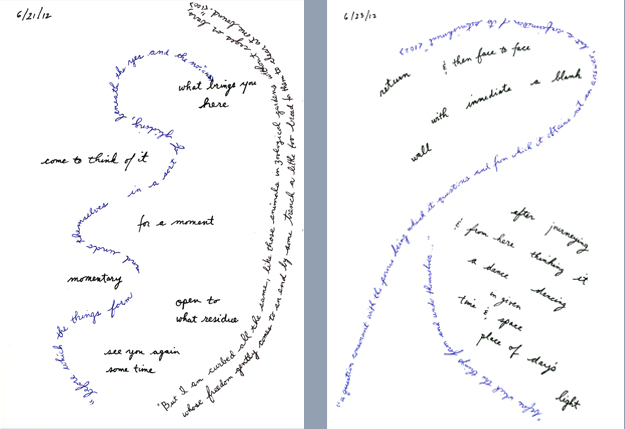

Robert Grenier has long been exploring the minimalist poem. Since the 1970s, he’s been straying, wandering, or maybe zig-zagging away from the notion of a poem printed on a page secured in a book. He’s made giant poetry posters with clusters of tiny poems printed here and there on them (one I have is tiny white typed words on black paper), and his famous “Sentences” is an elegant box of cards with little poems of a few words, or even one word, or part of a word on each card (“Sentences” is now also available online). In the late 1980s, he began to make what look like poem scrawls. Consisting generally of actual words (though they are often hard to make out), the works — which are shown in galleries — are quite beautiful. They are made with various colored fine-point pens (green, blue, red, black), not, as with Whalen, with calligraphy equipment in decorative alphabets. Precise thin lines bend, spread, and crisscross on large-format paper, building up a dense forest of lines in pleasing, if seemingly casual, though gorgeous, array, that only eventually resolves into words when you look at them for a while. Sample texts:

AFTER

NOON

SUN

SHINE

or

I saw it

where is it

(or it might read I saw/ where/it/ is it)

Deliberate, lovely, if simple or even simple-minded phrases, unlike Whalen’s offhand unintentional words (“B, a beard. … B. is just because … Don’t mention the Arizona Biltmore …”)

Image courtesy of Bob Grenier.

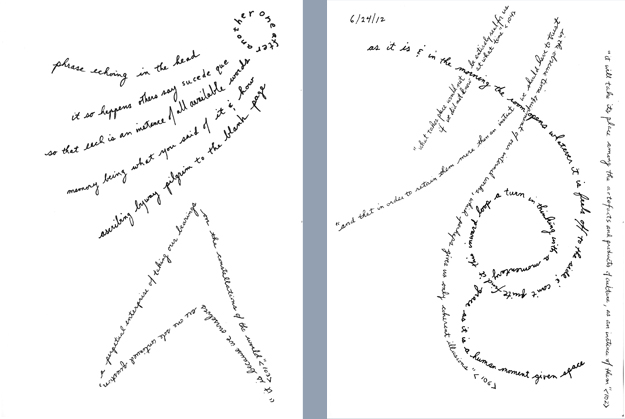

Hank Lazer’s shape poems are, again, something completely different. The words are handwritten in notebooks, one poem to a page, in series. The notebook is the aesthetic unit here, as, perhaps, with Whalen, though Whalen’s notebooks are what he referred to as “goofing,” while Lazer’s are quite deliberately in series. (Grenier’s scrawls are complete standalone poems). The handwriting of Lazer’s shape poems is not particularly elegant, as in Whalen, nor does it emphasize, as in Grenier, the emotional and visual primacy of letter and word. Using ordinary ballpoint pen (note that in later notebooks Lazer too uses a fine point instrument), Lazer’s hand isn’t particularly distinguished one way or the other. Just words written in an ordinary way, the writing somewhat chunky, not flowing. Their distinction comes in the shapes they trace on the page — spirals, squares, circles, various complex irregular forms. The twenty or so notebooks I am aware of begin with fairly ordinary stanzaic shapes on the page and evolve as they go into these more elaborate shapes, each page unique. Whereas Whalen’s word-content is rather haphazard and free-associational, and Grenier’s is precise, imagistic, or emphasizing grammar and syntax, Lazer’s words are discursive and poetic. In the course of the twenty notebooks he is reading through Heidegger’s Being and Time, and, later, several works by Emmanuel Levinas, and the words in the poems play off and dart in and out of citations from these works. The tone is philosophical and ruminative, a record, from inside language, of a person’s thinking, about words, in words, in and about time, space, life, death — not thinking’s products but thinking itself as process. The poems are improvisational and immediate — the form allows for no revision. In fact improvisation — its delightful freedom, playfulness, even joy — is characteristic of all three of these poets’ visual work.[2]

Image courtesy of Hank Lazer.

What is interesting and sustaining for me about the possibility of writing is that one could live in the intimate midst of words as such — as thinking in a shape, feeling, and form — as being in the world that’s illuminated through human mind and language, simply dwelling there with all the wonder and serenity that that dwelling brings. This seems to me to be the case with any writing that I find truly worthwhile, and the more you appreciate this the clearer it is that its pleasures come fullest at the level of the word in hand and eye and mind — as you find in these works.

1. Philip Whalen, The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen, ed. Michael Rothenberg(Lebanon, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 2007).

2. The most accessible example of Lazer’s shape poems is found in his N18 (Complete), Singing Horse, 2012. They can be found online in Talisman Issue #42 and Plume Issue #34.