'mend the world'

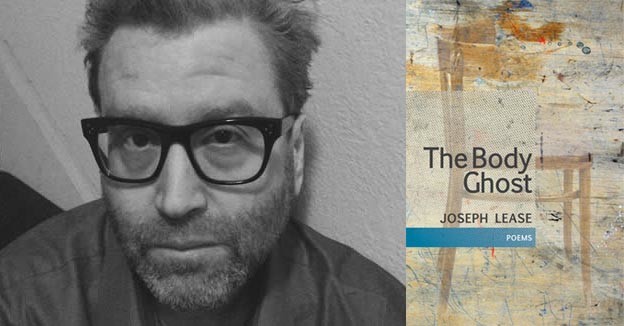

A review of Joseph Lease's 'The Body Ghost'

The Body Ghost

The Body Ghost

A father is at the end of his life. He is dying, and his son is in the room with him as he dies. In the elegy “Stay,” the father holds his son’s hand and says:

“when I

squeeze

your

hand I’m

squeezing her

hand”[1]

The dying father is speaking of his own mother — when he squeezes the hand of his living son, he is squeezing the hand of his own dead mother. The two living bodies are not alone. His son thinks to himself, “his mother / in the / room — / his mother’s / me —” (68). The son is himself, and the son is someone else. The son remains himself while his father transforms him into his grandmother. In this act of transformation, the father recovers how the love of his own mother felt, a love long passed out of the physical world, which returns in that last moment as an overwhelming memory triggered by physical sensation, a hand squeezing a hand. The living, the dying, and the long passed are together. Recovery occurs at the moment of crisis.

Joseph Lease’s new volume of poetry, The Body Ghost, is a book situated in a world in crisis; within crisis, the musical and figurative powers of lyric poetry can shepherd recovery. Poetry not only names the world — not only identifies what is broken and breaking down within it — poetry, in The Body Ghost, is a means of transformation, a saving action within the world.

In Lease’s poetry, crisis is rarely cast as the either/or of personal crisis or public crisis. The personal happens against the horizon of the public. Public ills threaten because they infect the lives of the populace. Written in the Bay Area, where rampant capitalism has driven the cost of basic housing to monstrous heights, where evictions are common and long-term residents all too often find themselves priced out of the city, Lease’s “Rent Is Theft” gathers together consumerism, war, and environmental degradation:

… just keep shopping —

eyes was I, dawn breaking, earth breathing:

just say missiles, just say drones: frack,

baby, frack: my eyes are made of cash and

going broke (45)

Consumerism, missiles, drones, and hydraulic fracturing come as a litany, fragments piled atop one another. The ills of contemporary America appear with a speed that feels breakneck — economic, military, and environmental violence juxtaposed against one another. These poems, written between 2010 and 2015, remind us that these ills were all too real at the end of the Obama administration, and they continue to speak to the present crisis during the Trump administration.

But even in this passage, the seeds of recovery exist. Public ills arrive in the poem as a series of fragments. Those fragments threaten to overwhelm but never do — the fragments can always be organized within the poem; handled; moved toward music. Lease asks himself (and us) to name these ills, “just say missiles, just say drones,” an insistence to speak in the face of violence, a refusal of passivity, a faith that naming the violence remains a defiance against injustice. And the Romantic beauty of landscape has not been wiped from the earth: “eyes was I, dawn breaking, earth breathing.” Dawn still breaks. At dawn, the poet standing in the landscape can still divine the breath of earth.

Public mixes with private. Crises shift to recovery. The distant nears until it is intimate. This is a poetry of transformation, a poetry where observation is a physical action, affecting the external world, Lease, and the reader alike. Continuing elegy in The Body Ghost, Lease begins his titular poem:

someone

scatters

someone’s

body:

ashes,

ashes,

let’s fall

and on the beginning of the next page “down” (79–80). Here the ritual for the dead body is first viewed externally: both mourner and mourned are an unknown “someone.” In the music of the child’s singsong chant, the ashes scattered become not only the anonymous body but the reader’s own body. Lease changes the expected words: not “we all fall down” but “let’s,” an action that the poem asks us to join in as it asks us to turn the page, complete the chant, continue the poem. The ashes of the external, mourned body become the ashes of the us. The words of the poet become our own, needing our hand to complete them. The dead, the poet, and the reader are joined by an altered childhood song and by our own hand.

Music is a common means of joining and recovery in The Body Ghost. The poems of the book are braided together in the repetition of phrases. Phrases like “say moon, say ink, say stay in love” (3), “I tore the page — I tore up the page” (19), and “democracy is anybody’s eyes” (20) appear at one moment in a poem, only to reappear later in the same poem or across other poems in the book. They link moment to moment, poem to poem. The poems of The Body Ghost are tied to the poems of Lease’s earlier books, phrases repeated and contextualized from the earlier work, and are tied to the larger conversation of lyrical poetry, phrases from the Psalms, Donne, Herbert, and Coleridge collaged into the lyric whole “O taste, O taste and see” (11), “and to your scattered bodies go” (37). The individual does not mourn alone. The member of a democracy does not face capitalism and imperialism alone. The sole person does not speak, read, or hear alone in these poems. Joined to the lyrical, poet and reader are part of a community of voices that have psalmed and sung before.

Remade in the poem, crisis transforms into music, phrases repeated transform in their new context. The Body Ghost is a book of transformations. The dying father of “Stay” not only transforms his son but transforms in his dying, and is transformed by the poem itself:

my father

rain

becoming

rain

rain

becoming

rain (72)

In death, he is not inactive, but a being that is still becoming. In these poems, language is not inactive but an action coming into the world. In Joseph Lease’s The Body Ghost, crisis changes to hope. It mends.

1. Joseph Lease, The Body Ghost (Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2018), 67.