Menacing archives

A review of Jennifer Scappettone's 'The Republic of Exit 43'

The Republic of Exit 43: Outtakes & Scores from an Archaeology and Pop-Up Opera of the Corporate Dump

The Republic of Exit 43: Outtakes & Scores from an Archaeology and Pop-Up Opera of the Corporate Dump

What kind of archive is the landfill? How do disposable technologies haunt — or annul — the imaginaries of urban ecologies? Landfills and wastelands often preserve more than personal and communal memories: narratives of city development, domestic and global economies, cultural infrastructures, and processes that underpin technological innovations. Indeed, as Jennifer Gabrys has cogently argued, the landfill functions as “a kind of archive, which assembles … through a default accumulation of wasted matter tightly packed in airless cells.”[1] Landfills and dumps, in other words, are vacuum-sealed sites of human record that enmesh natural environments with the often leaky afterlives of material cultures.

“Is it possible,” asks Jennifer Scappettone, “to mobilize the disgust provoked by encounter with what has been cast off, to transform a wasteland from an abject repository of undifferentiated filth into an archive?”[2] To speak of the landfill means navigating one’s reactive sense of revulsion toward the abject, the monstrosities that entrench their stink in sidewalk rubbish bins and dumpsters, and steep toxic particulates in genetic codes. However, too often we forget how integral waste is for both human habitat and the habitat of the poem. As Robin Nagle has expertly shown, New York City’s topography — like many cosmopolitan centers throughout the world — is comprised of garbage. Fill has helped to shore up its coastlines, extend the acreage of its surrounding islands, and terraform marshes and swampland in places like Staten Island. “20 percent of today’s metropolitan region,” writes Nagle, “and fully 33 percent of lower Manhattan, is built on fill, much of which was created from rubbish.”[3] In this light, urban developers refuse to demonize waste as civilization’s exhausted hauntings. To repurpose a quote by Gabrys, our cities — like landfills — are more akin to structures of “managed decay.”[4] Waste is transmutative, a temporary condition of unregulated purposeless that waits for its functionality to be restored when it is recirculated back into the polis.

Landfills, themselves, are also transitory terrains that acquire new capital once they’re slated for urban renewal. This has been the fate for former landfills such as Spectacle Island in Boston, Fresh Kills on Staten Island, and Syosset in Oyster Bay, Long Island, which have undergone — or will undergo — redevelopment into public parks and recreation sites. The dynamic properties of waste, then, cannot be underestimated: the dispersal of rubbish and fill into new environments far from their points of origin insists on new ways of seeing the pastoral. Even the capped waste mounds at Fresh Kills are fluid bucolics of composition and decomposition that nonetheless cannot be spoken about easily in terms of either purity or pollution. As much as they are responsible for staging formidable toxic biomagnification in marginalized neighborhoods, the landfill also sustains nonhuman species, local imaginaries, community identities, and childhood memories. “While the revamped Fresh Kills Landfill,” writes Scappettone, “presents itself as dry, sterile, bureaucratic infrastructure, it’s surrounded by juicy, clashing rumors and gossip” (102).

Like Syosset, Fresh Kills underscores the multifarious public and private contestations that are frequently fought on and over landfills and dumps. Opened temporally in 1947 as part of a real estate development plan to fill in Staten Island’s marshes, Fresh Kills eventually became one of the largest refuse sites in the world as successive regulations extended its lifespan. 9/11 aborted its closure in 2001 when the landfill accommodated rubble from the World Trade Center. Finally, in 2008, construction of the Fresh Kills recreation park began, although the landfill was once again pressed into temporary service as a staging ground for Hurricane Sandy debris in 2012.[5] The intermingling of recreation wildernesses and landfills seeks to further complicate notions of planned obsolescence when domestic waste is rendered legible into new cultural forms. The metamorphosis from sites of refuse to sites of refuge frequently speaks to not only the changing terrains of wastelands, but also the erasure of local memories that build around these former landfills. What kind of pastoral, then, is the hazardous waste site? How to make material and sticky its cancerous violence? Perhaps garbage and toxic waste should stick to us like burrs, not only because industrial contaminants pollute drinking water and soil, but also because they ground us in the infrastructures of failed regulations, racial injustice, and corporate complicity. “[T]rash,” suggests Scappettone, “serves as an acrid reminder of the elements of the oikos cast off in the interests of economy” (111).

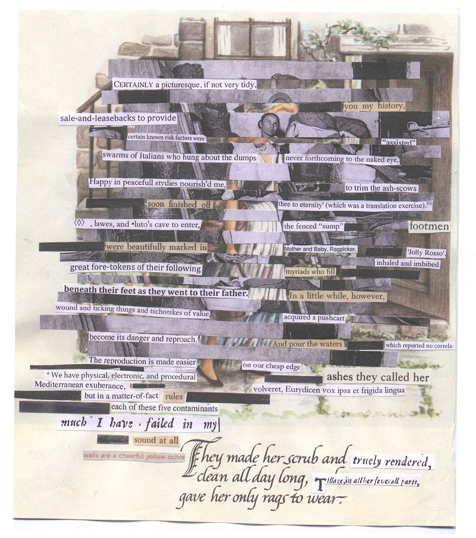

For the habitat of the contemporary poem, the waste imagination too occupies a pivotal role. Scholars working in the fields of literature and media, such as Jed Rasula, Christopher Schmidt, and Susan Signe Morrison, have highlighted the compostable aesthetics of textual trash.[6] Consider Wallace Stevens, who writes “The dump is full / Of images,”[7] or A. R. Ammons’s often cited lines “garbage has to be the poem of our time because / garbage is spiritual, believable enough / to get our attention.”[8] Material and linguistic waste makes further aesthetic claims in James Schuyler’s “The Trash Book,” Brenda Coultas’s The Bowery Project, and Ron Silliman’s Sunset Debris. In Meddle English, Caroline Bergvall urges us to “imagine the midden of language.”[9] Jennifer Scappettone takes us through a different ecology of waste in The Republic of Exit 43 to interrogate the landfill and its contents as textual and visual collages of discursive, legal, social, networked, and childhood knowledges. Her down-the-rabbit-hole narratives invoke the landfill pastoral, where the “infrastructure of cancerous byproducts may trail the infrastructure of planned obsolescence” (103). Here, the illogic of industrial and domestic waste encounters Virgil’s The Georgics and the nonsensical syntax of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. To this end, the resultant collection undertakes an archaeological dig that excavates the literary, journalistic, commercial, and digital vocabularies that dovetail into toxic waste sites, including the former noxious copper rod mill and landfill of Oyster Bay, where Scappettone once lived.

There’s a risk in flying in an airplane, a risk in crossing the street.

In a canal becoming, a village, becoming a creek.

“That funereal coast …”

Thickly powered with the motes of an atmosphere granular, pollenous, edible and instinct ...”

Teeming with people, entertainment, experiences, and opportunity. (30; italics in original)

The poetic line becomes another thick layer in this textual landfill where preexistent language from sources like Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is uprooted and restitched to the tragedies that still seethe below difficult places like Love Canal. Now buried under its new name of Black Creek Village, Love Canal reconnects the reader to the involuntary memory of “ecochemical calamity” (16) that cannot be contained in drums or by soil. Here, the poetic line is another layer of corporate dirt to be dug, another airless cell to be cracked open and exposed to the writerly surface.

These geotexts suggest a landscape of discursive mounds, collaged with the shifting real estates of texts and imagery. Like landfills, visual and textual collages mix temporalities and spatio-materialities, colliding together the weighted histories of nuance-rich fragments. Arguably, here, Scappettone activates the memory of Baudelaire’s ragpicker, albeit without its heroic tones, by unearthing and recirculating these textual debris. Her sources — among which are Jacob A. Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, Sir Philip Sydney’s “The Defense of Poesy,”and a Cinderella picture book — grapple with their new regulations in the collage. “Ragpicker and poet,” writes Walter Benjamin, “both are concerned with refuse, and both go about their solitary business while other citizens are sleeping; they even move in the same way.”[10] Rethinking collage as a ragpicking ecology demands a confrontation with cultural disgust toward the filth and biohazards we shamelessly generate, and the implicit iconographies of danger and safety that are often entrenched in consumer products.

the tailings blowing into tiny throats

stuffed with vitamins to make them sharp

as piles nationalize and reprivatize their fault

of lead like bankrupted Doe Running in the fosse of separated

corpuses while diggers picket for soft environmental standards

and are gassed from Cobriza to Herculaneum

(or Herky as the locals say) to school

kids heap the fire with copper bales

then with their lungs remove the tape at Agbogbloshie quick

— remember that? (46)

How can poetry utter a vocabulary of “a multinational sprawl / of diversified environmental mishaps” (15) in the Cobriza copper mine and the La Oroya smelting plant, where sulfur dioxide and lead have contaminated the water and soil of the Peruvian landscape? What kind of citizenry is possible in places like Agbogbloshie, a former wetland in Ghana, which is currently home to one of the largest electronic waste dumps in the world? Cobriza, Fresh Kills, Syosset, and Agbogbloshie are tentacled with each other; their particularities fold within the globalized processes of waste distribution. Scappettone has written about the regime of input/output in The Republic of Exit 43, but it’s worth repeating that the textual and visual collages in this book disturb the stability of site-specificity of waste and landfills.

In this review, I’ve struggled to articulate the way that Jennifer Scappettone animates the materiality of her subject: literary scholarship is still catching up to syntax of slow violence still buried under landfills.[11] Yet The Republic of Exit 43 foregrounds the persistent encounters with archives of abjection in which we, by our humanity, are all implicated. At stake is the fate of ecocritical discourse in light of the proposal H.R. 861, a bill recently introduced to terminate the Environmental Protection Agency. The future erasure of environmental security intersects with the current alienation of the landfill-cum-recreation park. Histories are still caught in the undertow of leaking garbage.

1. Jennifer Gabrys, Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 130.

2. Jennifer Scappettone, The Republic of Exit 43: Outtakes and Scores from an Archaeology and Pop-Up Opera of the Corporate Dump (Berkeley, CA: Atelos, 2016), 99.

3. Robin Nagle, Picking Up: On the Streets and Behind the Trucks with the Sanitation Workers of New York City (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), 48.

5. Eric Lipton and Kirk Semple, “NYC revives Fresh Kills landfill for storm debris,” Star Tribune (Nov 17, 2012).

6. See, for example, Jed Rasula, This Compost: Ecological Imperatives in American Poetry (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2002); Christopher Schmidt, The Poetics of Waste: Queer Excess, Ashbury, Schuler, and Goldsmith (New York: Palgrave, 2014); Susan Signe Morrison, The Literature of Waste: Material Ecopoetics and Ethical Matter (New York: Palgrave, 2015).

7. Wallace Stevens, “The Man on the Dump,” in The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), 201.

8. A.R. Ammons, Garbage (New York: Norton, 1993), 19.

9. Caroline Bergvall, Meddle English (New York: Nightboat Books, 2011), 6.

10. Walter Benjamin, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire,” trans. Edmund Jephcott, in Selected Writings Volume 4, 1938–1940 (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2006), 48.

11. On slow violence: Rob Nixon, “Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor,” Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies 13–14, no. 2-1 (2006–2007): 14–37.