Life-in-death: an agonizing in-between

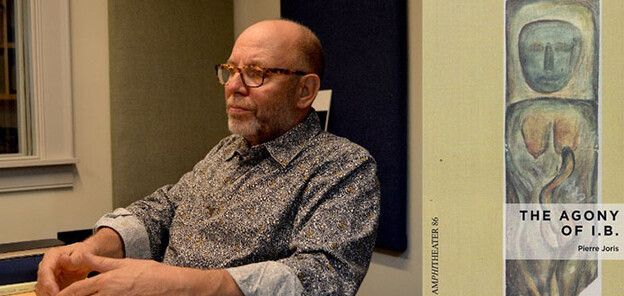

A review of 'The Agony of I.B.' by Pierre Joris

The Agony of I.B.

The Agony of I.B.

We’re all going to die; very few of us will have a death as remarkable — or perhaps as unremarkable — as Ingeborg Bachmann’s. It is against this canvas, the final days of Bachmann’s life as she lay comatose in an Italian hospital, suffering from burns — the result of a fire caused by a wayward cigarette — and the pursuant withdrawal from sedatives, that Pierre Joris sets his play The Agony of I.B. (2016). The play, commissioned by the Theatré National du Luxembourg during Joris’s time as writer-in-residence and presented during their 2015–2016 season, attends to Bachmann’s death as a way of exploring the insolubility of the self under threat by desire. The play takes on this problematic by examining the purgatory-like gap between the two (the self and desire; the self and the other), naming it and giving it size and shape, drawing its lines and contours. Indeed, it is this concept of the middle ground or barzakh — a liminal space between life and death, between the individual and the other (and echoing Joris’s 2014 poetry collection of the same name) — that runs through the play, connecting the body of the dying Bachmann in her hospital bed to the vibrant and sardonic Bachmann of the flossy imaginings — perhaps better to call them dreams — played out on stage, beyond and above her comatose body.

The play introduces us to this trope in its first moments. We find Bachmann in her home — but not at home —in Rome, where “Ti amo translates as I hate you, tourist whore. Because I cannot be in Vienna. But I am writing Vienna.”[1] From her earliest utterances, this berating self-talk, we understand Bachmann as a stranger, an outsider, a “tourist whore,” undulating between where she is and where she wants — desires — to be. Writing might get her there: it serves as ersatz for what she cannot have, for the Wien perpetually deferred. “I have to move back to Vienna, it will happen later this year, as soon as I finish this … As soon as I’m through wandering the desert, there’s something more to learn from the desert” (16). “Later this year” will never happen, at least for her, and perhaps somewhere beyond her conscious self-berating she knows this, knows that, like the “desert generation” having fled Egypt to wander the midbar for forty years, the “desert” is as far as she’ll ever get. Besides, this Vienna, the Vienna she is “writing,” is not the Vienna she would return to. Bachmann is resigned to, indeed, needs the “desert” for her art: “Yes, I can finish the book by writing into the middle now, returning to the desert, that other empty page. Am in the desert anyways, Vienna will be desert too, my past, all past is desert, desert peopled by ghosts” (16–17). To write, Bachmann must remain in and with the desert; she must write “into” this space “in-between sand and sky. The in-between that is not just the page but that is time, in-between time” (17). This “in-between” forms the “other empty page” Bachmann invokes earlier, where “other” should be taken to mean both alternative as well as wholly distant, unassimilable, and perhaps even sublime.

The more she speaks — to herself, to us — the more the complexity of this “desert” comes into focus, as not just place, but as time as well, as “[t]he in-between that is not just the page but that is time, in-between time. Time is in-between, in fact that is all time is: an in-between. What was the word Mohammed used? Bar … bar … Bar-zakh” (17). She stumbles towards the word in a sedative-induced haze, stuttering, yet recalling this word from the Quran (chapter 23, verse 100). Her stuttering reinforces the difficult, ungraspable nature of this temporal and spatial liminality: she approaches with language, with a word that, even in capturing it, breaks around the contours of the concept’s excesses — Bar-zakh — the hyphenation emphasizing both a slowing and trepidation in her voice as well as elongating the word, stretching it in her mouth and on the page, as it stretches to fill all that is “in-between.” Though she calls this space, this “desert” or “in-between,” “past,” the play refutes such a notion, making clear through repeated invocations of her past — making the past very much present — that a temporal schema of past, present, future should not be assumed and that Bachmann’s own life may be read as an elongated, stretched and contorted “now.”

The play develops by way of a series of (re)encounters between Bachmann and former lovers Max Frisch, Hans Werner Henze, and Paul Celan; interactions with these three men structure the play’s three acts. Though sculpted around the biographical events of Bachmann’s death, the play extends, by way of these encounters, beyond the realm of the knowable or “real.” Joris writes into the openings of these relationships, teases them into new directions that cannot be addressed or answered through the archive. It is his writing onto and past the known — the documented and biographical — that allows Joris to create a space that exists between the “real” and what lies beyond, into a space between life and death. The play is itself a middle ground, formed by inextricable units of fact and fiction, a space in which the impossible, unimaginable encounter may occur. The play frames this woven zone through dialogues between Bachmann and the three men. However, the meaning of “between” as prepositional conduit — as implying communication and connection — must be understood as under threat of erasure, since each of these encounters challenges and undermines the possibility of any “true” or “authentic” encounter.

In scenes with Max Frisch, stage directions note how the two remain in separate pools of light and “talk as if they were in dialogue — there will be parallel crescendos, a bit opera-like — but they always talk past each other — un dialogue de sourds as the French say — their talk never meets” (25). Politically and emotionally, their “talk” never meets either: Frisch prefers being at a remove and is hesitant to “engage with that much outside anymore,” determined to “build against the wilderness” (25). In contrast, Bachmann opens the window to her room and recites her poem “My Bird” to an owl outside, “as if to entice [it] to enter” (27); she desires to bring the “wilderness” in. The poem ends “I’m ablaze at night / and the dark thicket begins to crackle / and I strike sparks from me! / ablaze, ablaze & loved by fire” (28), foreshadowing the fire that will soon envelop her, but also highlighting Bachmann’s artistic fervor, and contrasting Frisch, the “homo faber,” keen to construct a rational world, “a house more rational than its builder” (25).

Bachmann’s encounter with Hans Werner Henze in the second act, after the fire and her hospitalization, is equally fraught, with the distraught Henze calling out to the comatose Bachmann and receiving no response: “Can you hear me, Inge. Please, please say something. Tell me you are there … It is me, Hans, your brother, your other … I need to see you, to know you are alright … Touch you, Ingechen” (39). They do “touch,” but only in an imaginary scene-scape, parallel to the “real” of Bachmann’s hospital room. This shift from reality to fantasy will intensify up through the play’s conclusion: projected scenery will replace the effects of the hospital room, leaving only the bed, a totem to Bachmann’s mortality, but also a door to another level of existence. It is for this reason that the players, when moving from hospital room to fantasy world, “appear” from behind the bed, in what Joris refers to as “a deus ex machina” (45). Set vertically on the stage, Bachmann’s deathbed becomes a physical manifestation of a middle ground, connecting one world to the next, this world to that world. It also situates the action taking place in front of the bed as concomitantly above it. In this way, the actions that take place in Bachmann’s dream-state play out above her deathbed, in a space between life and the afterlife.

Through its own undulation between reality and fiction, as well as from Bachmann’s physical situation — immobile, under an oxygen tent — to her psychic dreamscape, the play performs as its own barzakh, as a middle ground between biography and myth, simultaneously confusing neat, progressive time and cohesive, singular space. Through this maneuver with time and space, we come to understand Bachmann’s death — as well as her dying, a progression traditionally understood as teleological — as itself a movement from one realm of being to another, as a progression, yes, but lacking beginning or end, where telos is replaced by the continuous unfolding and enfolding of states of “in-between.” As these states fold and unfold one is confronted with an emptying stage, mirroring Bachmann’s death — an emptying of her physical body. Yet the projected scenes of landscapes — both mountainous and desert — which replace the physical set pieces articulate an opening-up of the space and transport Bachmann away from her death bed.

While Joris establishes the barzakh as the theoretical cornerstone of his play, he also uses the concept to effect a kind of theatrical distancing akin to Bertolt Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt, an effect of distancing by way of making foreign the quotidian. Each act opens with a prologue in the style of a Weimar cabaret, upsetting the somber, contemplative pathos of the play. Adolf Opel, one of Bachmann’s later lovers, plays the congenial host, joking with the audience and playing the ham. He is countered by the “straight man” of Maria Teofili, Bachmann’s housekeeper and confidant. Teofili’s propensity for the melodramatic, referring to the play as “the drama of a life lived without love — not without lovers” (14), clashes with Opel’s facetious description of the play as a “real tragedy, whatever real may mean. But certainly a glorious tragedy” (13). Neither Opel nor Teofili appear as “real” characters, and their exaggerated and contrasting affects situate us from the first moments of the play in an undefined theatrical space, in another type of undefinable middle ground between comedy and melodrama, yet never comfortably falling into either.

Opel’s jokes are not funny, nor is Teofili’s dedication to Bachmann endearing: rather, the repeated scenes with these characters remind us of the artificiality of the work itself. An emphasis on artifice is key for Joris, who, like Brecht, does not want his audience to become immersed in — and thereby passive towards — the contemplative pathos of the play. Rather, he wants an audience that is cognizant of art as artifice, and who thereby come to understand art as endlessly referential rather than singularly representational (something akin to Theodor Adorno’s idea of “autonomous” art, but still at ease with Brecht). The composition and decomposition of the set emphasizes this move. As the play progresses in the second and third acts, the setting shifts between a realistic hospital room to an open space decorated by projections of various landscapes. While neither setting is elaborate, the use of projections creates an openness opposed to the sterile containment of the hospital room. The play ends, not in the hospital room, but in this open space with the image of “a painted door” (9) (Joris suggests that this could be Irving Petlin’s “Red Door,” but what is most important is that the image be “a work of art,” again emphasizing this middle-ground between reality and art, the barzakh that mediates between art and the “real”).

The barzakh, winding its way like a red thread through the play, comes to a moment of crescendo in the final act. Bachmann is visited in her fantasy world by Paul Celan, who had died by suicide over three years earlier. The dialogue between Bachmann and Celan is the most complex and layered of the play: they speak in what sounds at times like a language of their own, a personal language that mixes details of their lives with lines from their poetry, such as “In Egypt,” a poem written by Celan in his first letter to Bachmann in 1948. Joris animates much of this letter correspondence by transposing its themes and language from the archive to the mouths of his characters. Their split recitation of the above-mentioned poem ends with Bachmann cutting off Celan and reproaching him for his suicide, “When you left I did not lose you, I lost the world” (68). Such a reproach — and that she would still reproach him — illuminates the unfinished nature of their relationship, that their affection and desire for one another extends beyond this world.

Bachmann makes clearer their connection as exceeding the material world when she describes Celan and herself as “dreamed ones.” She insists that they “dreamed each other more substantially than blood and flesh” (82), establishing a relationship of excess, a relationship that exceeds the material body and human life. Within such a dynamic, death is no longer an end but rather an access point to true contact with the other. Such an understanding of the dream leads one to reconsider the space of the barzakh, this middle-world and dream-world, as the only space in which one can hope to reach the “other.” Understood as the space of the dream that exceeds life, the barzakh no longer appears as a mere purgatory, an uncertain space between life and death, but a space available for true encounter, a space of certain possibility. It is the space for the exile who “dismissed long ago / and provided with nothing / cannot live among humans” (96–97). Bachmann recites these lines from her poem “Exile” as a form of adieu to those in the audience, we, the living, who cannot join her, who must wait for language to “carry us aloft” into “brighter realms.”[2]

1. Pierre Joris, The Agony of I.B. (Soleuvre, Luxembourg: Éditions Phi, 2016), 15.

2. These final citations are taken from the concluding line of the poem, “Exile,” purposefully not reprinted in the play, and translated by the reviewer. The poem can be found in Ingeborg Bachmann, Sämtliche Gedichte (Munich: Piper Verlag, 2015), 163.