The letters of the alphabet and letters to the dead

A review of 'Two'

Two

Two

I: Two slim volumes

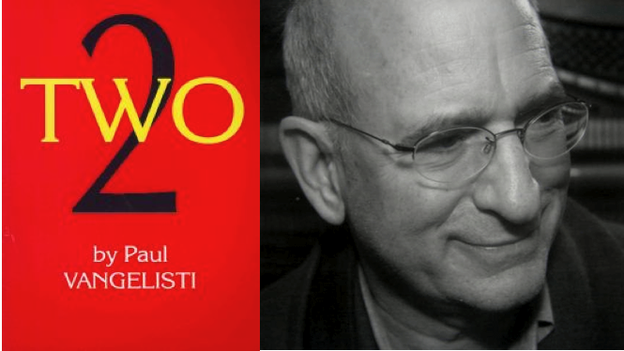

Paul Vangelisti’s newest collection, Two, despite being only ninety some pages long, is comprised of two distinct, chapbook length sequences. The cover design reflects this by superimposing the black numeral “2” over a yellow “Two” on a bright red background. But the mood of the contents is much more subdued. Maybe characterizeable as a muted palette blend of the cover colors—resulting in a quiet, brooding Burgundy with glints of winter sun?

The two sections of Two are very different, but what they do have in common is a quizzical maturity on the cusp of aging. A sense that memory’s a meager compensation for what’s lost. And that the better part of what’s to be gained in life, has probably already been gained. This isn’t “late life” work. Vangelisti has only just turned sixty-five and the material in Two goes back some years. The tone seems more reminiscent of that George Simenon memoir, When I was Old, which ends around the age of sixty with Simenon’s nagging sense of mistrust for what may come. In contrast with the same author’s late life Intimate Memoirs. That Simenon tome, despite some true intervening miseries, ends with the now really old storyteller, intimately and serenely consoled and warmed by his young Italian housekeeper-mistress.

II: A is an Angel

Letters and Letters

Alabaster, the first half of Two consists of twenty-six musings loosely inspired by a sequence of alphabetically sequenced words — from Alabaster … through Pall, Quotidian, Reliquary, Sacristy, Tabernacle, Unction, Voluntary, Xystus, Yes, Zuchettto.

The second portion of Two, is cryptically entitled A Capable Hand, Or Maps for a Lost Dog. This section is comprised of XXXIV Roman numeral designated posthumous letters to Adriano Spatola, an Italian poet and close friend of Vangelisti who died suddenly in 1988. From a poetic standpoint their friendship was deepened by translation. Vangelisti and Spatola each translated each other, and Spatola introduced Vangelisti to other contemporary avant-garde Italian poets, who he translated and published over the years.

In Two, Spatola seems both a friend still mourned and a friendship still cultivated. In 1996, Vangelisti began a large project — the translation of Spatola’s collected poems. Although Vangelisti had translated and published a number of the Spatola pieces previously, he set out to begin afresh, rereading and retranslating rather than simply revising. The project was assisted by a translation grant from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. And the result, Adriano Spatola The Position of Things: Collected Poems 1961–1992, published by Green Integer in 2008, won the prestigious American Academy of Poets Raiziss / de Palchi prize in 2010.

Translation as Conversation

The letters to Spatola in Two represent a ten-year plus, ongoing conversation with the friend Vangelisti was simultaneously translating. But perhaps, “letter” isn’t the best descriptive. Each piece begins and ends with a stanza of poetry. As in V:

How heavily the foot is accented,

don’t let the message stop you

this far into the service,

morning has been sentenced to love

This is followed by a prose reminiscence of attending a Christmas Mass at St. Peter & Paul’s in San Francisco offered by an Italian-accented priest:

“Christ,” said the Italian priest at the Chinese Mass on Christmas morning, “died on the cross because he ‘lafed’ …” The entire Mass was in Chinese, except for a few minutes of the sermon in heavily accented English. I was there with my father. It had been many years since I set foot in church. I couldn’t keep the tears out of my eyes the more Chinese I heard. Only the English stopped me. God is ‘laf’, said the priest repeating the Christmas message. When the service began, I stood in the pew glaring straight ahead, a loaf of bread we had just bought under my arm. My father kept repeating something like ‘amon’ along with the Chinese until I asked to leave. Amon, Egyptian god of life and reproduction, revealed as a man with a ram’s head.” Christ’s”, concluded the priest, “is the kingdom of heaven ‘an dearth’.”

All those years at the kitchen table,

only mothers and fathers asked to leave,

there with a loaf of bread under my arm

until just now your laughter catches me.

At a recent reading from Two, Vangelisti explained that in this portion he wanted to present both a prose and poetry version of the same piece. What I’m also struck by, especially in the multilingual aspects of the piece quoted above, is the parallel between the process of translating poetry: The migration from the original poem to a prose “trot”, a sort of conversation with the poet you’re translating. Then, after the necessary internalization, a rebirth as a poem in a new language.

A recurring alphabet and recurring letters

Those familiar with Vangelisti’s previous work, especially readers of his selected poems, Embarrassment of Survival will quickly recall both the themes of an alphabet sequence (Aleph Again 1999) and of letters (Villa 1991). Aleph Again, in fact, is dedicated to Spatola and begins:

A is an angel who wants absolutely nothing. She looks elegant in torn trousers and almost never answers the phone. She seldom speaks, especially when spoken to. Right now A’s on Adriano’s lap making him laugh.

III: Stevens and Williams

Two lines of descent?

This is obviously an oversimplification, but for explication it might be helpful to think of two lines of descent from two early century modernists for two approaches to contemporary American poetry. One, coming from Wallace Stevens, tending towards the abstract, the cerebral, conceptual. A lyrics of ideation. The practitioners of language oriented poetry would fall into this camp.

The other lineage, descending from William Carlos Williams, tends toward more concrete, narrative, discursive images. A poetics in which all other aspects are subordinate to communication. A broader, more transparently outgoing, reader-centric group. Vangelisti, as a poet and also as an editor has always seemed to manage to have a foot in both camps and still walk, even dance, without stumbling.

Alabaster, the alphabet sequence that constitutes the first half of Two, tilts toward the aesthetics of ideation as opposed to imagery. “Tilts” rather than embraces that aesthetic, because while Vangelisti may flirt with a “language” aesthetic, his willingness to wholeheartedly embrace it seems always undercut by his sense of humor. While humor may be subtle, it’s never hermetic. It mocks self absorption and can only live by communicating.

Alabaster opens with an epigraph by Ray Di Palma that seems a good summation of the attitude Vangelisti wants to explore with this sequence: “Hey, Presto, where’s the elephant? / And what have you done with the other half of the girl?”

A matter of form.

In an after-note to the alphabet sequence Vangelisti talks about “moving outside the approved forms toward a different vision of language, an alphabetic burlesque of constraint” where “the text resists with words speaking in time and place, at once language’s conscience and its promised land.” This last is, for me, a maybe overly cerebral pronouncement. But what follows quickly redeems it: “To paraphrase Orson Welles, this must be Los Angeles; my horoscope at breakfast told me to choose words carefully when speaking to myself.”

It took several poems to spot what Vangelisti meant by “moving outside … approved forms” into “an alphabetic burlesque of constraint.” The alphabet is present not only in the sequenced titles, but in two other ways. Each poem consists of twenty-six lines. And each line begins with a sequenced letter. As in the “ABCDE” opening sentence of the poem Alabaster.

Almost anything between joy and survival, / both anxiously here to needle a tragic bearing, / comfortable besides with things, speechless things face up or / down, commonly lavender or sometimes blue with that/ everyday delirium born from the briefest pleasure …

And its “VWXYZ” ending with: "Various unfulfilled desires exposed in a remodeling / without vain hope beyond profit, a lump, a spasm in the night, / xeric, that mauve citizen of ritual and doubt, / zealous you find that inch of satisfaction in contriving."

Into or Out of a Form?

Inveterate sonneteers sometimes remark that an unanticipated conclusion of a poem, even the sonnet’s turn, often occurs to them as an adjunct to the rhyme scheme—that in trying to find a rhyme something new and elemental can appear out of nowhere. In trying to find metaphors for the difficulty of translating formal poetry into formal poetry, I once threw out the concept that poetry was: “language that talks back to you with something that can’t be said any other way.” And that the craft of formalism required writing “out of” rather than “into” a form.

Although both camps would resist the comparison, I’ve often thought of the new formalists as simplistic second cousins of the language poets. At their extremes, both schools share a self conscious addiction to theory that can defeat practice by stifling the germ of poetry. The danger for the retro neo-formalist is that of writing into rather than out of a form. Of settling for obvious rhymes and metronomic meter, because the form rather than the poem becomes the goal. The danger for the language poet, I think, is a coy opacity, an aristocratic refusal to name anything by its common name. This also can remove huge energy sources.

So has Vangelisti — writing language oriented poetry with his new (as opposed to received) form — managed to navigate the Scylla and Charybdis of both schools?

Is Vangelisti writing into or out of his new form? I would say, mostly out of. How else could an obscure adjective like xeric (deficient in moisture) marvelously appear? And is xeric’s languagesque characterization as “that mauve citizen of ritual and doubt” too opaque? I think it’s not only the smile of burlesque that saves it, but the weight of common, charged language in the, albeit, oblique image.

If there’s any criticism I might have of the way Vangelisti navigates the triple-alphabet concept, it’s that to fully enjoy some of the poems it helps to be conscious of the form. But in others, such as Hermitage, the lines work without any consciousness of form:

A bit like I came, I saw, I got swankered in this place / best Asia Minor of the intellect money and fear / can buy. Kiss me once and kiss me twice and the third O the third / doesn’t count for much besides nostalgia for bread buttered / evenly down both sides

Or Sacristy:

About beauty they often had so little to tell us / beyond a laconic smile that took your breath away, / covering belatedly the occasion of whim left / desperately coveting even the glimpse of a faux heaven

You might, by the way, wonder how Vangelisti handled twenty-six xs. There aren’t, after all, that many x words. As he observed in his 1999 Alephs Again:

X is too imposing for words. There’s only one under X in my thesaurus, X-shaped, and that’s too chiasmal.

Chiasm another word I had to look up, an x-shaped intersection or crossing. Merriam Webster online offers that it rhymes with orgasm, phantasm, sarcasm. See how easy it is to get caught up in this stuff? But as far as X-words in the twenty-six-poem sequence, Vangelisti conveniently uses his unique form’s counterpart of off-rhyme: words like expectations, exfoliation, exaltation. Although in other poems. he does manage:

x-rayed with their derbies, fedoras, even children’s messy heads

And:

X looks delirious with longing for your dreamy boulevards.

Not to mention a sort of “XYZ — burlesque” tour de force in the ending of Yes:

Exactly X willing the ding-ding-ding-ding-ding-a ling-a / yes with your work and someone who loves you genuinely much / zip zap, pretty blue skylight outpacing the elemental.

Mercy

Smack in the midst of all this wordplay, halfway through the alphabet, unexplained and plaintive, is Misericord. A title word which Vangelisti notes at the bottom of the poem has two meanings:

“1. A bracket attached to the underside of a hinged seat in a church stall, against which a standing person may lean. 2. A narrow dagger used in medieval times to deliver the death stroke to a seriously wounded knight.”

Misericord breaks the sequence with 26 lines of un-patterned verse and accessible, evocative images. Going back to the Stevens / Carlos Williams metaphor: A good portion of the alphabet sequence challenges the reader’s attention, not unusual for a descendant in the Stevens thread. Misericord on the other hand is an exception that whispers in what might be the reader’s own voice. Misericord begins:

All along, beautiful mountains may crumble but our love

isn’t at all where it ought to be holding up the whole

damn baggage — stars below in the street, the echoing house,

the shimmering O my desert, a small door, a gentle rain

twice blest, heartbreak or lemons in the fog, those graceless

repetitions plus or minus thirty-two. Where is the harm,

where the tenderness in losing oneself for so many years

in lost causes, in winning forgeries for endowing

a life of rime? My littlest sister, when just a wrinkle …

And ends:

What do you see besides a guy who’s been winning and losing

the territory for too many years, who hasn’t forgotten

even if it took his appetite more than fifty years to

remember to? Have any of us, even in this

second-hand city, any idea of how you break my heart.

IV: Spatola again

Ghosts and Epigraphs

The second section of Two also opens with an epigraph, three actually, and in contrast to the Di Palma epigraph, they’re almost funereal:

The first from Dante’s New Life: “I would give expression to my grief and send it to this friend of mine, so that it would seem I had written it for him.”

Then, a quote from a Spatola’s Stalin Poem: “silence is no better than lying.”

And a Jack Spicer line: “We ghosts, lovers, and casual strangers to the poem”.

So there’s not much surprise when the first prose conversation with Spatola opens:

Look Andriano, it’s what I said to them: the dead prefer restaurants when they’re closed. A Sunday morning after a rain, restaurants like the one we were sitting in, ran along the avenue like banks or Presbyterian churches with their parking lots empty and that postcard blue sky. They like bread almost exclusively, in fact I’ve never heard of them eating anything else. This time it looked like both of them might smile. What do you think, I said, that the dead will swallow anything? Just because they listen and seem to agree with whatever we say doesn’t mean they’re gullible. It’s just good manners

For me, this conjured echoes of Rilke’s Orpheus Sonnet #6:1: “At night, when you go to bed, never leave bread, never leave milk on the table. It draws the dead.”* The opening epigraphs were appropriate: This is a big, traditional theme and, as Joseph Brodsky once observed, we write as much, if not more, to impress our poetic forebears as posterity. Isn’t poetry of a certain ambition, always an implicit conversation with the dead?

Still, the unpretentious conversational tone of Misericord carries forward in the second portion of Two. And why not? These are, after all, quiet conversation with a dead friend and translatee. Sometimes we’re not sure who’s translating whom. From II:

What was it Pasolini called death, “the alibi of Catholic slaves?” Writing must make you uncomfortable. So Catholic of me. And what about translation? Think of all the days and years: to fly 7000 miles and ride several trains, to arrive at a river in a valley at the foot of mountains, to sit in a millhouse before a glass of wine and a poem and start translating

Who do we talk to when we talk to dead people?

Whether or not you believe in an afterlife or ghosts or lingering protoplasm, after you reach a certain age you find parents and close friends you’ve lost never seem to really depart your dreams. I guess there’s a difference between conjuring the dead while awake or in dreams, but I’m not sure what it might be. And, really, if it happens — either dreaming or daydreaming — isn’t conversation with a dead person the only truly guileless conversation you can have? We, don’t so much lie, but — can really never manage the unembellished truth with our living friends, lovers, parents, kids. And we do lie to ourselves all the time.

There’s a certain generosity between the dead and the living that seems courted by the funeral banquet. I remember my mother’s banquet outside Queen of Heaven cemetery in Chicago; a sad-eyed, exquisitely gentle Mexican waiter urging a comfort bowl of mashed potatoes on me while fraternally squeezing my shoulder. Did I sense my mother was passing the bowl when I realized all our petty, generational quarrels had not only evaporated like incense, but were henceforth impossible?

It’s only in discussions with the dead that complete openness is possible. The visiting ghost understands us beyond any possible designs on us, an alter ego that only asks to be acknowledged. And if, to boot, that ghost is a poet who brings poems to be translated, then he, indeed may seem to be something akin to Orpheus in Rilke’s Sonnet 7:1:

one of the enduring messengers. A friend,

who deep within the portals of the dead, still

offers the glorious fruit and the brimming bowl.*

Or as Vangelisti’s II continues:

It was as if this game of metaphrase and two-mindedness, played at your kitchen table or mine, continents and years apart, came before or sometimes replaced how are you, what have you been doing, how does it feel to be living alone? Sure Pasolini postured and exaggerated, but don’t we all when we’re alive? Did I mention, by the way, that I had been hired to teach creative writing at Occidental College? Where your “Seduction Seducteur,” if you recall, was done as a dance. It’s a private college, founded some 120 years ago, Presbyterian in intent, meant to spawn upright, successful young men and women. Robinson Jeffers attended in 1904, brought here by his father … The old man picked the college for moral reputation … Anyway, Jeffers attended though I don’t think graduated before running off with a friend’s wife. So we translated from a day or so after we first met, April 2, 1975 to that last stifling afternoon in Sant’llario, drinking Pernod and repairing someone else’s translation, Thursday, July 21, 1988. Time being at the moment parenthetical, I write in English without translation. Odd how in death a word seems more than what was available in life. Animal in the dusk, is it you or me with a house and a job and the right wine glasses finally?

By the way, did I mention the need

for parentheses, like the possibility

of running off with a friend’s wife,

untainted by time after time of

replacing how are you with what

are you going to do with that bottle?

And what was Adriano saying all this time?

Ghosts, after all, visit us from a place we’re in no hurry to get to, and their end of the conversation isn’t always all that sunny. Their very presence is a memento mori. Maybe to get a feel for the poet Vangelisti was talking to, and for some of the messages he was delivering, it might be well to give Adriano Spatola the last word.

Vangelisti chose a recurring phrase from Spatola’s, circa 1970, poem The Next Sickness (La prossima malata) as the title of his collected translations. The second and third stanzas of that six stanza poem seem to serve as well as anything as an example of Spatola as poet and Vangelistis as translator, in duet.

2. consider first of all the position of things

the common cold the saw mill screeching in your ears

the syllabic clamor of water from the faucet

presence and absence shortness of breath digestion

a wet body’s odor is synonymous with perversion

or excessive prudence or a spark in the retina

something beats on the temples we must open the head

3. consider first of all the position of things

you’ve become cordial you’re not complaining you smile

behind the house the grass begins to grow

with its sweet lice green like the green of the grass

this itching that you scratch is called spring

jeweler and hydrochloric acid silver and clay

be careful of drafts to the heart to your thoughts

* Rilke: my own translations