ko ko thett's cannibalistic poetics

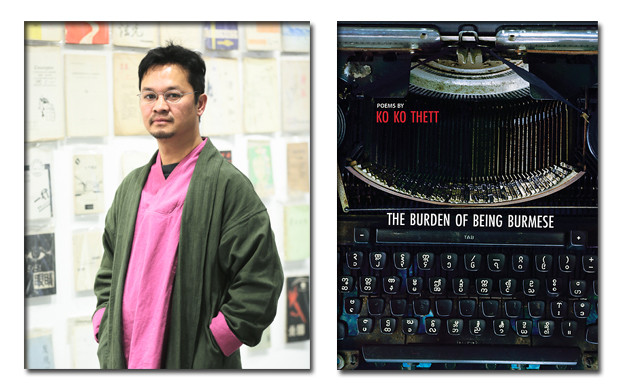

A review of 'The Burden of Being Burmese'

The Burden of Being Burmese

The Burden of Being Burmese

We don’t choose the world we are born into. Or the nation. As valuable as theories of the social contract may be — the idea that we chose to relinquish the freedom of unfettered existence for the security of a lawful society — the fact remains that no one in our world has ever actually confronted that choice. It’s not a contract we can annul.[1]

The quintessential modernist response to this problem is to imagine oneself as part of a larger, supranational tradition — that of the literary canon or of Western civilization — and so to stand, in a sense, above history, above the nation. From the vantage point of that longing, it’s not as hard to understand Pound and Eliot’s fascist sympathies. In a modern world too overwhelming to contain, too full of despair and angst, there was comfort in the bucolic fantasy of the volk as much as there was in the sense of having been born late, in the wrong time, “an old man in a draughty house.”[2]

ko ko thett’s poem “my generation is best” reads like a child ironically placating false nostalgia of a parent. The child teases:

childhood past life, polio sister, measly brother, river blindness,

tetanus twitch, bookworm, hookworm, head louse, earthworm

… playing football in the downpour with those low-income diseases

isn’t your generation best[3]

As with so much of thett’s work, even while the poem goes on to skewer generational nostalgia, the simple irony of the opening stanza unravels into more nuanced indeterminacy:

there was no income inequality in your days, everyone was equally poor

no capital flight, there was no capital

... the government never needed to justify its policies through

pro-government policy think-tanks to appease the west

Was life better in a world before neoliberal market logic sublimated all government policy decisions? Was life better before capital?

thett’s poems live within these questions, unwilling to cede an ounce of their undecidability. This is the burden of being Burmese — the burden of asking questions with no good answers, the burden of choosing between only bad options — and it’s a burden that we all share. If the modernists confronted the overwhelming sensory carnival and perpetual political unrest in the metropolitan centers of late-stage capitalism and pined for an imagined Edenic past, thett’s poetics presents a different solution: eat everything. Raw. In “a few ways to eat a city raw,” thett observes that “only humans, and a few other alien species, can eat on their feet” (13). In a world of limited resources, eat when you can, where you can, how you can. The best possible moment is the present; it’s the only one that exists.

The Burden of Being Burmese is thett’s first collection of poetry, but it reflects nearly twenty years of writing by a poet who has already left his mark on contemporary world literature as a translator and coeditor of an anthology credited with introducing Burmese contemporary poetry to Western audiences, Bones Will Crow: Fifteen Contemporary Burmese Poets (2012). It’s less surprising, then, that Burden doesn’t read like a first book, but rather an artfully and athletically constructed meditation on politics and poetry from a man raised in Myanmar, now exiled in Europe.

The book’s primary poetic habit is the list: thett’s lists are slapstick, capacious, contradictory, free-wheeling, vengeful, and above all cannibalistic. If thett’s ethic is based on eating everything, his poems attempt that impossible feat by piling it all into the stomach of the poem, each morsel separated only by a comma. “urban renewal” is a litany that expresses the frenzy of urban development plans, apparently as fervent in Myanmar as in the suburban expanses of the United States:

dog parks for dogs,

amusement parks for amusements, child-friendly facilities

for the parents of children who may never grow up,

bingo halls for all ages and sexual preferences, clear the

woods on the city’s fringes for nine-hole golf courses,

logging shall be licensed to make way for streamlined

taxiways for international arrivals, plant garden plants

in every department store (28)

thett’s list runs on and on, “malling, walling, enthralling”(29), painting a Bosch-like landscape of the banality of development schema in which organic life becomes demarcated units with assigned spaces, even if that entails clearing forests while planting gardens in department stores.

As much as thett’s depictions of heady speculation, consumer fantasy, and crony capitalism place this collection in the context of an emerging global culture (as much as “the burden of being Burmese” is everyone’s), the book also offers a window into the particular social and political history of Myanmar. thett wrote the majority of these poems in English and the book is published by a Massachusetts-based press, so he writes of his home country with an awareness of his audience’s loose knowledge of its culture, language, and history; the poems swerve between the roles of translator, cultural critic, travel writer, tour guide. The portrait we get is of a country plagued by decades of colonial and civil war, and still under the burden of autocratic military rule. We learn of the official “People’s Desire,” a legislated worldview that the government has required all publishers to print on the opening page of books and magazines. We are given a tour of a military town named for Colonel Ba Htoo, a national hero who fought against the Japanese during World War II: “the town that honors the anti-fascist hero is a purpose-built / breeding ground for the ultra-nationalist myanmar army / where can you find a better irony” (19). And everywhere the poems signal evidence of severe wealth inequality: “our clinics supply the intolerably rich with aphrodisiacs and antihypertensives / our pharmacies provide betel and beedies to the filthy poor” (15). These poems move beyond pat dichotomies, noting that the choice is often between bad and worse.

thett’s politics are grounded in the scholarship he has published on Burma’s politics and economy. In a 2012 report, commissioned by the Burma Center Prague, thett argues that the current Myanmar Responsible Tourism policy is “doomed to fail” and leaves the door open for “crony capitalism at the expense of political, ecological and cultural sustainability.”[4] His chapter in Totalitarian and Authoritarian Discourses examines the deep-rooted myth in Burmese political discourse of the indispensability of the military.[5] Fairly direct lines could be drawn between the preoccupations of his poetry and scholarship.

But to note the seriousness of thett’s politics risks missing his deep commitment to humor, particularly sound play. The phrase “flip-flops” appears throughout the collection, at times echoed by the phrases “flip-flap” and “flap-flap.” His poem “after ‘the lie of art’” is a slapdash tribute to Charles Bernstein’s poem of the same title. The delightfully campy poem “timely applause and toothy smiles” would be at home in any of John Ashbery’s more recent collections. Humor is no answer to the fraught political questions at the heart of this collection, but given that thett hails from a country where desires are legislated, it is perhaps not surprising that he turns to humor to unsettle assumptions, to shake loose language.

Laughing along with thett may hurt. It may catch in your throat. There is no promise of redemption here. “[Y]ou don’t want to be another down comforter” (71), thett tells us (and maybe himself) in “the rain maker.” That said, in gestures reminiscent of the work of Derek Walcott (or other Caribbean poets), the collection often uses symbols of water, the sea, and marine life to suggest a world apart. There is an ode to a river, another to a sea, and the tale of “the day he regretted swimming butterfly” across the Baltic with a beer can in his hand. Water and its inhabitants flow freely across the lines drawn by nations, in spite of them. Poems attempt something similar.

1. This point is more fully elaborated in J. M. Coetzee’s novel Diary of a Bad Year (Penguin, 2007), 3–5.

2. T. S. Eliot, “Gerontion,” The Complete Poems and Plays (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1958), 21–23.