Gelmaning on

A review of 'Oxen Rage (Cólera buey)'

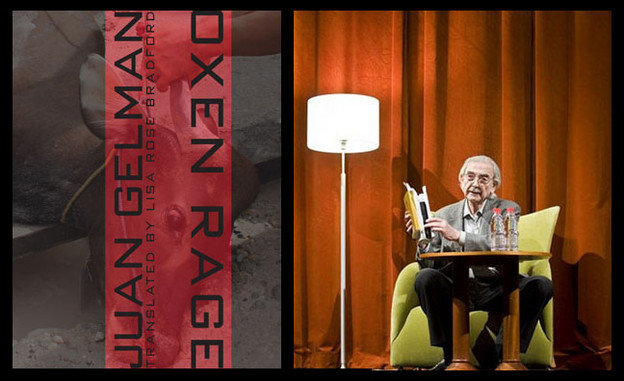

Oxen Rage (Cólera buey)

Oxen Rage (Cólera buey)

Remarkably few volumes of poetry by Juan Gelman have been translated into English. This is perhaps because of the unique challenges inherent in translating his work, known for its neologisms, playful and musical language, and political exploitation of ambiguity — Gelman once wrote to his translator, Lisa Rose Bradford, “To be sure is a sickness of our times.” Yet, as a poet who turned to translation to broaden his creative resources, Gelman’s work, I would argue, is not resistant to translation but rather uniquely receptive to it — provided the translator has the guts to tinker with one of the most influential Spanish-language poets of the twentieth century. Bradford rises to the task with a poet’s courage and imagination.

Bradford has previously translated three volumes of Gelman’s poetry, including Commentaries and Citations (Coimbra Editions, 2010), Com/positions (Coimbra Editions, 2013), and his Carta abierta titled Beyond Words: Juan Gelman’s Public Letter (Coimbra Editions, 2010), which includes commentary and an interview with the author, and won the National Translation Award. These books pertain to Gelman’s incredibly fertile period in the 1980s, during which he experimented with writing intertextually, conversing with poets of the past and of his own invention, breaking and reinventing language. While this recourse to experimentation may have been spurred by tragedy — he was exiled from Argentina shortly before the military dictatorship of 1976–1983, while his son and pregnant daughter-in-law became bodies among the estimated 30,000 disappeared — its roots begin much earlier, as Oxen Rage demonstrates. The book collects the remains of eleven unpublished books written between 1963 and 1968, coalescing around a long elegy for the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara. Oxen Rage is suffused with the violent optimism of the 1960s, and it is this willful refusal of despair in the face of gathering political darkness that engenders the “stubborn obstacles”[1] of the book’s oxen-like language.

Bradford’s is not just the first translation of Oxen Rage into English, but the first into any language. Complicating — and liberating — her monumental task, is the fact that the book includes Gelman’s first forays into pseudotranslation, of the invented poets John Wendell and Yamanokuchi Ando. Even Gelman’s own voice is far from fixed, moving from expansive free verse to intricate meter, prose poetry, and evocative fragments, to extended elegy, but always reveling in musicality, sometimes without regard for meaning. As Bradford writes in her introduction to Oxen Rage, “this medley of genres and approaches to writing poetry in many ways springs from translation, in the most energizing sense of the word, translation being an occasion to open up the language for it to become enriched by reinvention” (xiii–xiv). Bradford’s challenge is to translate without pinning down ambiguity, to create distinct voices in English while allowing each to bend and change. In doing so, she benefits from a long artistic friendship with Gelman, a poet who viewed all acts of writing and translation as “con/versational” (xiii).

Bradford offers unusual insight into her translation process in her introduction, where she shares the literal translation through which Gelman’s poem “Yes” passed on its way to her final version. Readers unable to recognize the Spanish neologisms in Gelman’s en face original will see his linguistic innovation in Bradford’s literal translation: “celebrating its machine / the dog-stubborn heart love-dwells / as if it weren’t given (struck) crosswise / back winging in its defiance // winging of flying wing” (xv). Already, between parentheses, we can see her mind moving from the vague literal to a more visceral verb. Compare those intriguing yet unintelligible lines with her ingenious version:

celebrando su máquina celebrating its engine

el emperrado corazón amora the dogged heart enloves

como si no le dieran de través as if it weren’t battered on the bias

de atrás alante en su porfía wingforth and back in its defiance

alante de ala de volar (38) forwarding wings to flight (39)

By not translating literally, Bradford achieves that rare alchemy of English poetry that has the texture of Spanish poetry, while being true to Gelman’s unique voice. Her poem revs open with an engine that fuses human and animal, animal and machine. The brilliant “battered on the bias” slants wing-like to catch a rhyme with defiance, propelling the poem forward as it hovers between heaven and earth. The tension between wings and feet stretches the poem diagonally: “troubled by stones / underfoot like feet of a sort // feeting along rather than winging or how / the world the ox the enloined would be / if we weren’t devouring one another / if we were enloving more lavishly” (39). Gelman appears torn between the desire for escape and the daily struggle of life on earth. He praises the loyalty of the ox, who appears here not as stubborn (to a fault) but a lover, enloined, giving life. Elsewhere, Gelman plays with changing the gender of nouns, while here he transgressively attributes maternal qualities to the castrated draft animal. The coinage “enloined” (“lo que se hija,” literally what sons) is reminiscent of a pun Gelman has borrowed elsewhere from César Vallejo on “hijar/ijar,” “to son” with “flank.” Bradford mimics the structure of Spanish, finding sonic echoes by repeating prefixes in sometimes familiar, sometimes new ways, as in engine, enloves, endeavoring, enloined, enloving. Capturing Gelman’s neologisms is a weighty responsibility in this poem in particular: “de atrásalante en su porfía” and “el emperrado corazón amora” became the titles of recent books in 2009 and 2011, respectively, proving how Gelman’s experimentation in Oxen Rage has continued to reverberate up into his final works. Having now fixed their titles, we can only hope that Bradford will fill in the poems encompassed by these later volumes.

According to Bradford, Gelman likened his moments of poetic inspiration to “A horse galloping on my chest.” In another poem, “Heroes,” Gelman animalizes himself by making his own name into a verb, gelmanear — “my thing is to gelman” — something he will continue to play with in later books, including Carta abierta. He also creates verbs from nouns, as in the poem’s opening, “the suns sun and the seas sea” (35), which benefits from fortuitous puns in English. The sun and sea can’t help but be and do just what they are, yet humans often strive to escape our animal nature. Not so with this poet, who celebrates ranch animals without romanticizing them. In this poem, the animal of metaphor is a horse, and the focus on castration remains: “we have lost our fear of the great stallion / successive hatchets are upon us / and it always dawns upon our testicles” (35). The work animals in these poems in some sense function as a critique of capitalism — “all poetry is hostile to capitalism” (265), he writes — yet Gelman was equally critical of the strictures and dictates communism imposed, particularly when it came to literature. With a clever intervention in the last stanza, which in Spanish simply begins “a gelmanear a gelmanear les digo” (34), Bradford clarifies what sort of animal Gelman is: “giddy up gelman on i say / go gelmaning on to meet the most beautiful ones / those who launched victories in their great defeat” (35). To gelman is to gallop through life, to push on against despair and exhaustion, but it is also to be ridden, to be worked. Bradford’s translation of “Heroes” in the book doesn’t differ much from an earlier draft published in Asymptote, but one can appreciate how she has streamlined certain lines, such as the opening, embracing the declarative power of Gelman’s simple language. Another translation of the poem, by Katherine Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez published in their beautiful critical tribute to the poet after his death in 2014, which adheres to and departs from the original in sometimes the same and sometimes different places as Bradford's, allows the reader to appreciate just how much translating Gelman is an act of interpretation.

Gelman titles the collection Oxen Rage after the second “book,” foregrounding the significance of these poems as a nexus of future linguistic inspiration. Yet, his experimentation in other sections extends also into the formal. “Sertimientos” / “Sertiments,” the title of which plays on the common practice in porteño dialect of substituting r’s for n’s, is a stupendous example of formal verse, with a driving rhythm of octonario (sixteen-syllable lines) formed of pairs of eight-syllable lines connected by a caesura, and a chaining rhyme scheme over five cinquains. How to translate a poem like this? Bradford wisely does not attempt to replicate the rhyme, and the syllable counts change slightly, but she retains the paired construction of the lines across caesuras, which comes quite naturally to English poetry, by way of Beowulf:

like a wisp of a cry like a wee little bit

like a pebble’s flight of catenating light

i untether my horses and tie up my patience

nightbound voices raise their two voices

nightbound branches raise their two voices (69)

Following Gelman, Bradford repeats words or uses conjunctions to connect the two phrases across the gap, finding internal rhyme in places. Terms of bondage proliferate throughout the poem, mirroring its unchaining structure, which Bradford translates adroitly, finding synonyms that multiply meaning: “and the beasts of love roam unchained / and they sing but don’t sew those Machiavellian tailors / who stitchlessly seamed your heart up with mine / and lashed their fate with barbarous sweetness.” “Lashed” puns wonderfully on tying, but also whipping, coming as it does in close proximity to Gelman’s horses. This is a poem that moves with the inspiration of wild horses, beasts unchained, while patience is tied up and left behind in the stable. The lovers in the poem strive against fate, personified with the classical trope of a tailor: “the barbarous tailors doublestitch the wrack and ruin” (doublestitch, another wonderful choice for what in Spanish is simply “atar,” to tie) (68–69).

And what fate do the lovers strive against? A new refrain replaces the opening “nightbound voices”: “it’s fear outside it’s hunger it’s cold / and it corrupts and kills and shrivels the bond.” Love must be very strong to survive fear and poverty born of political repression. But the lovers are not innocent: “those black devils just as your love and mine / with their tender pustules and pure indecency / sing like the devil it’s hunger it’s cold / and arise through the fault of all innocence.” The paired contradictions tear against their binding, and speak to a painful romantic bond that perseveres against external forces and its own inherent instability. As the poem comes to a close, phrases are recycled for a devastatingly inevitable conclusion: “i untether my horses they intone their two songs / without saying it’s fear i gaze at the infinite sky / your heart and mine tether their wrack and ruin / and at one fell stroke they crush it’s hunger it’s cold” (69). While “Sertiments” sings with the modernismo music of Martí and Darío’s formal verse, it speaks to the reality of a disaffected generation in 1960s Argentina.

The refrain of hunger and cold recurs later in sparser free verse in one of the poems of “Other Mays,” which warns those who persist blindly, ignoring the injustice of the world, “careful now it will get dark / get hate get hunger get cold” (129). With remarkable consistency, Bradford matches the reverberations across Gelman’s Spanish in her translations, ensuring that these throughlines can be followed in English, as in the opening of “Another May”: “sunny people who stroll / along the skin of may / strolling people strolling along / doggedly defiant of the world” (129), which recalls the famous neologism of “Yes.”

Now that we have a more or less firm grasp of Gelman’s voice (as if that were possible) we can appreciate the poetic achievement of Gelman’s pseudotranslations, and Bradford’s translations of the pseudotranslations. The poets Gelman has invented here are British (John Wendell) and Japanese (Yamanokuchi Ando). A plausibly Japanese surname, ando is also the first person singular of the Spanish verb andar (to stroll or walk), so it is almost as if Gelman is saying, “I go around being Yamanokuchi.” Gelman’s relationship to his imagined poets is one of embodiment. To his credit, and Bradford’s, Ando’s poems do not mimic the aesthetic minimalism and meditative contemplation that is often associated with Eastern poetry in translation. While Ando employs metaphors of the natural world, he also engages with the Western poetic canon in poems about Sappho, and Greek and Arab mythology. His best poems, quite unlike Gelman’s, tumble in a single sentence of sounds spread out across several stanzas that grow stranger and stranger as they go on, as in the ending of one of the Sappho poems: “roses growing there and when / they rotted on her tongue / they left her damage sweetness / death and double blooms of thought” (345). Here, Bradford has preserved the proliferation of d-sounds in Gelman’s “original” — “le dejaron daño dulzura / muerte pensamientos dobles” (344) — which drag the poem down with heaviness. Unsurprisingly, for a poet enamored of Sappho, Ando excels at erotic poetry, as in poem II, which is also composed of a cascading thought that here finds a sense of resolution at the end:

love not spent on full orgasm

with a woman if a man with a man

if a woman sucks the salt

from kidneys crackles

in the lungs killing joy

vexing the cervical and a caress

changes rock into clay

deafly coursing through the body like

other disappointments or brightness

in this world so replete

with baseness betrayal rooms

that begin to moan at night (337)

While Ando’s erotic poems begin to resemble Gelman’s minimalist intonations to an absent lover in “Sefiní” / “Say Finis,” they are more surreally metaphysical. Bradford makes lovely choices here again, such as making “sordo” into an adverb, “deafly,” that can also be read as “deftly.” With Ando, Gelman creates an innovative, contemporary voice that forcefully opposes the regionalisms imposed on Eastern — and, for that matter, Latin American — poets.

In translating Ando, Bradford tacks closely to her method for Gelman’s own poems, writing good translations that preserve, when possible, the aesthetic qualities of the Spanish (without in this case any obligation to sound like Spanish). The task of translating John Wendell, from Gelman’s Spanish “translations” into their English “originals,” is arguably more challenging, and Bradford rises to it tremendously. It is not their local reference points that make Wendell’s poems read as distinctly British — “nor do I know why these reflections / fall like snow in Charing Cross where I love you / and sink down into you as into a river / of ambrosia and milk and honey and I love you” (247). Nor is it because, as a poet concerned as Gelman was with the postcolonial political reality, his worldview is shaped by the borders of the former and current British Empire:

I am a man of the world interested

in the revolution in Pakistan the lack

thereof in Yorkshire where

once I saw people weeping

from hunger or mere rage. (239)

(Consider how universal Gelman’s concerns in his own Argentina are shown to be, when Wendell expresses worry over the hunger, rage, and lack of revolutionary drive to combat them in Yorkshire.)

Bradford’s translations of the pseudotranslations of Wendell are glorious because they work poetically like poems originally written in English, as when she translates the wordplay of solo/sol (alone, sun) as “your name rises every morning / warming the world and setting / alone in my heart / aloft in my heart” (242–43). Or when XVII enjoys internal rhyme in its opening stanza, “with the breaking of day again / the house begins to grate / and it may be ghosts or some ward- / robe some forgotten memory falling apart,” and in the same poem, desgarramos is broken to enhance the meaning of the line as “where once upon a time we tore our selves apart” (237, emphasis mine). But most especially, when Wendell remakes one of Gelman’s signature themes in an unmistakably English vernacular, replete with rhetorical questions, yet with an alien enjambment:

and who dares to claim my heart is madness?

and who dares to claim my heart is not madness?

who is it dancing below who

is it guessing below dear friends

the favorites of hate and of time that gulps down hate

and all those tiny sparrows that are blameless?

and who swears that Panama is Panama and not your hair

when snow has fallen and we have made love like beasts

and delicate as beasts

and sad as beasts?

so much need for god’s sake

that’s how we’ll end up good god

dumb or half blind but always

rigorous in our assessments (233)

It is in her translation of the colloquial expressions that Bradford brings Wendell into a believable English, translating compadres as “dear friends,” and diós mio and mi diós as “for god’s sake” and “good god.” Yet what could be more Gelman than making love like beasts? What could be more British than ending a love poem with “rigorous in our assessments”? (233).

In the face of American poetry’s increasingly alarming insularity, Gelman’s revolutionary book demonstrates the rich “con/versation” that can only come from engagement with other languages and traditions. Bradford’s translations finally extend the conversation and the afterlife of these seminal poems. Only in translation can we appreciate the success of Gelman’s pseudotranslations, which force the reader to consider what makes a poem sound like a particular language or culture, what expectations we bring or limitations we impose on international writing. In Gelman’s polyphonous voice and Bradford’s translations we see reflected both the particularity and universality of great writing.

1. Lisa Rose Bradford, introduction to Oxen Rage, by Juan Gelman, trans. Lisa Rose Bradford (Normal, IL: co-im-press, 2015), xi.