'Collective poesy'

The disruptive pleasures of Caroline Bergvall's 'Alisoun Sings'

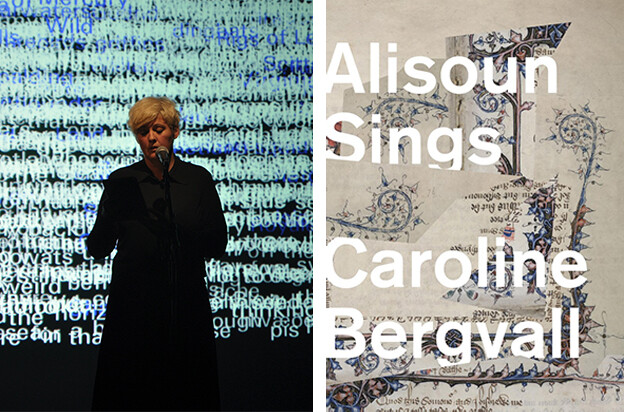

Alisoun Sings

Alisoun Sings

During an interview from the afterlife, Jack Spicer tells Hoa Nguyen that in making a poem, “you start with a syllable machine and see what ghosts you catch.” Similarly spirited, Caroline Bergvall’s Alisoun Sings channels a polyphonous “voice-cluster”[1] of pop stars and feminist icons of art and literature, all centered around Alisoun, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath. Together across time, Bergvall and Alisoun form a “collective poesy” (104) through queer networks of affiliation to explore pleasure’s physical and linguistic role in disbanding the national ties that constrain us and allowing us to re-form in new, more livable configurations.

Refusing uniformity, Alisoun inhabits the gaps and overlaps between Middle and contemporary English. Of her own language, she says, “’tis a rich scrambljumbl of heavily crossbedded bitching tongues, folded like shells in tymologick tension, so is ma usage a happy combiness, simpel” (4). Her intermingled dictions make her simultaneous proximity to and distance from the modern world a feature of her speech itself, bringing her into an interstitial state of then-and-now-ness and allowing her to draw on all present and former times to imagine a way forward.

Bergvall describes the original Alisoun as a protofeminist for her refusal to be chaste — a serial wife, she defied convention dictating she should remain sexless after her first husband’s death. Bergvall’s Alisoun opts for “bountyful booties ov all kinds & kins entwined revling ydizzied” (2). This Alisoun’s queerness exceeds sex and the individuals involved in it. Notably, she also recognizes contemporary queer genders as biodiverse proliferations, which complement and expand possibilities for “femaled and differential beings” (50) rather than threatening cis womanhood: “biosex makes all kinds of flowerings / but the rest is cohabitation and cooperatings” (114). Our interdependences point the way toward a “transformation of the worlde” through intimate connection that engenders a “networked spirit of soul beings / against the isolation of the fear machine” (114). This is a queerness that doesn’t begin or end in the unit of the couple. It connects, unlimits, and animates us in multigenerational “energy fields” (114), where we can meet each other and move together toward a “larger future, collectivized without / sacrifice” (115).

Speaking to and through the poet in a rush of heady anachronism and often in the words of others, Alisoun knows everything Bergvall knows and more. She has wide-ranging tastes, and she’s well acquainted with the dance hits of recent decades (the “IDJ2MANY” section is a torrent composed of lyrics ranging from Prince to Missy Elliott, Kate Bush to Nina Simone, Donna Summer to Kelis). The collective pleasure of the dance floor offers us one experience of coming together to form new physical and sexual constituencies, which Alisoun relates to literary lineages and then moves out into the streets. Invoking Octavia Butler, Carolee Schneeman, Audre Lorde, and Kathy Acker, among a throng of others, she chants, “They say that, the women I love, they say: / I’ve tried to tell of a world that doesnt exist to make IT exist” (37). To tell it, she needs to draw on the “school of beings” she has both learned from and become, embodying the crowd in herself. In the crowd, we are more than our own individual needs and desires. As ME O’Brien writes in Pinko Magazine, “Care in our capitalist society is a commodified, subjugating, and alienated act, but in it we can see the kernel of a non-alienating interdependence.” O’Brien sees care work as containing potentials for experiences of pleasure, which we can learn to “generalize” rather than relegating it only to sex. Likewise, listening to Alisoun is an experience of the widened pleasure of connection, the satisfaction of mutual work to make sure everyone gets what they need from the dance floor outward.

In “A cracking tale,” Alisoun tells the story of the world she wants to see, and it is dripping with wet, viscous, all-consuming love:

in the slots of evry ATMs egg over evry screen egg over evry street camra egg in dust particles and air particles running down streams & rivers egg in the linings & buttons of evry uniform egg in the lines of the holograms of bankcards passports ID-cards railcards. You name it throughout Summer we dropta love we dropta love. Love juice lifeyolk running sticking into evry figment imaginable! (27)

Alisoun’s vision of fluid sensuality swells erogenous tongues towards a natural utopia where human bodies restore their connections to the earth, overwhelming the violent structures of nationalism until “the trees smelt of sex & yolk & purpl blue! Pleasure collapsed the city the countryside the whole country, its release possesd us all” (28). The ATM, security camera, ID card, and uniform are sites of our daily interfaces with power. In Alisoun’s vision, sticky, uncontainable love makes a mess as it spills out into public space, gumming up the machinations of financial exploitation, surveillance, border enforcement, and policing. Like the lifeyolk, the cumulative desire of her syntax (“evry screen … evry street … evry uniform”) wells up and runs over, dripping into and across the lines meant to divide us from each other and queerness from public life. From the pleasures found in this disorder, we can re-form a more loving world. But more than a fantasy that queer sex will, on its own merits, revolutionize the world, Alisoun’s vision is one that demands action — the egg won’t get into the ATMs unless we get out and pour it in there.

Inviting us into the street, Alisoun describes the sound of collectivity:

Yes, says the crowd

says the wave of the crowd

says the sound of the voice of the crowd (107)

and then, voicing Clarice Lispector, she says, “Everything in the world began with a yes” (108). Lispector’s creation story continues, “One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born.” If we cluster, grow broader, aggregate, say yes to both ourselves and the needs of those outside our own immediacies, Alisoun suggests that we will be in good company for the work of pleasurable, collective living.

To do so, we need to look both backwards and forwards, to “make a concerted desperate purpous of simpler / connected living and get into bed with th’Earth / like a lovely and brave Mendieta” (117). Using her naked body as a material, Ana Mendieta left human traces in the natural world, denying the constructed separation between us. In her liaisons with Alisoun, Bergvall allows the many dead to talk through her and offers us a method for finding our own reconnected pleasure: say yes and then yes again and take the egg together.

1. Caroline Bergvall, preface to Alisoun Sings (New York: Nightboat Books, 2019), viii.