A child's history of conflict

A review of 'Hardly War' by Don Mee Choi

Hardly War

Hardly War

Before we reach the table of contents of Hardly War, Don Mee Choi’s concerns are clear. The epigraphs set three boundaries. Choi sets up Gertrude Stein as a foremother, whose style she will adapt and whose words she will intersperse with the other voices of the text — “It is funny about wars, they ought to be different but they are not.” Roland Barthes’s discourse on photography as “a shared hallucination […] a mad image” prefigures the text’s discourse on photography, its interweaving of treatises on photography, and the reality/unreality of war. Lastly, C. D. Wright reveals the major plot of the book, “her father filmed the carpet-fucking-bombing in Cambodia.” Confirming Wright’s truth, the dedication “For my father,” is accompanied by a photo of a man dressed in military gear and carrying a movie camera through a body of water.

Hardly War is a hybrid text that mixes poetry, photography, correspondence, narrative prose, songs, drawings, and, finally, a play. Choi tells the story of a young girl whose identity develops through this hybridity. The capital to build a house and start her family comes from her father’s journalistic war photography: “I was born in a tiny, traditional tile-roofed house, a house my father bought with award money he received for his photographs of the April 19, 1960 Revolution.”[1] Where her home and body emerge from photographs of revolution, her international identity is similarly hybrid: “A Korean term, uri minjok — our race, our national identity — was imagined, a crucial construction […] This is how nation=gook was born […] even our clothing became racialized and geopoliticized”(3).

“Race=Nation,” the first narrative prose section, works as a preface and is more expository than most of the book. At the other end of the book, there is a notes section that may be taken as a partial history or glossary or as an expansion of the poetic text. From the introductory pages we know that the setting of the book is South Korea, where the speaker, a young girl, grows up during the Korean War. We might identify this speaker as Don Mee Choi, although the text switches between narrative modes and narrators so frequently that the narrative “self” is fragmented. As the book progresses, we watch the Korean War unfold at home while Choi’s father, a war cameraman, simultaneously photographs and sends letters from wars abroad, such as the Cambodian and Vietnam Wars.

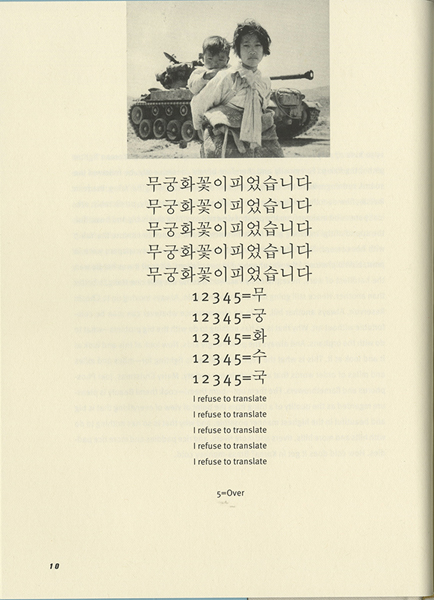

In “Woe are you?” Choi writes of the problem of being born/being a child in a country at war: “I hardly existed without DDT” (7). The American army invaders bring multiple forms of poison: DDT and “bubble gum, which GIs had to show those kids how to chew” (6). The invader provides “charity” but only for a limited time — only poisons for a little while. The “BIG PICTURE […] War and its men” contrasts with the people “in” the war, the children; the official message of WAR and its BIGNESS contrasts with the true picture of a little girl with paper dresses and her father who is “hardly himself” (7). The blocks of narrative are interrupted by a page with a picture of a child carrying another child on her back with a tank in the background. The text here, which is in Korean, is followed by “I refuse to translate,” and is taken from a children’s game, like freeze tag or hide-and-seek, where the chaser covers her eyes and then sings, “the flower is blooming” (10). The national flower and patriotism are inscribed in this untranslated children’s song, which recurs later in the book and sets the stage for the final “play” in the “Hardly Opera” section. Unless the reader goes out of their way to translate the song and find out its cultural relevance, the meanings of this section remain opaque. The English (“I refuse to translate”) is not a translation of the Korean text above it. The narrator seems to want to hide and protect this childhood song. Perhaps the experience of living through the Korean War as a child is also untranslatable to American audiences.

The language of the invading US soldiers, who enter Korea on June 27, 1950, is crass: “Merry Christmas, Joe! […] Fire them up! Burn them! Cook them!” they say (9). They buy brass monkey trinkets and describe Korea as “brass monkey cold” (9) a reference to the oft-elided fourth monkey in the “hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil” trio who covers his genitals, i.e., “cold as balls.” US military leadership says, “That’s a good sight for my old eyes” (18) — about seeing Korean men dead — fighting a war against them on their own land. For the invading military, the land is foreign and its beauty nonspecific ugliness — an alienation that allows them to destroy the land and people without remorse. “Beauty is pleasure regarded as the quality of a thing from the point of view of everything that is big and beautiful in the highest manner possible, and that is so has nothing to do with hills and more hills” (9). If we become familiar with it, perhaps we can prevent ruining it, because it is too well-known and well-loved. For the child, the nonsense language of the military mixes with the nonsense language of childhood: “Are you OK, ROK?” (11, Republic of Korea, South Korea), “cheerily cheerily red and merely merrily” (11, echoing Stein), “Yak and Yak,” (11, a North Korean fighter jet), “Shitty kitty” (39–41, Kitty Hawk, a US Naval aircraft carrier).

“Part III: Hardly Opera” is the most formally experimental part of Hardly War, where the cast of characters described in previous sections seems to speak to each other. The form is dramatic and the content operatic. The book’s trajectory has gone from memoir to multimedia to a cacophony of voices, including the voices of Korea’s national flower, children’s songs, and military equipment. There is no musical score for this section, but there are stage directions for percussive sounds, such as “shaking pine needle branches” (58) and “shaking red hydrangeas” (59). Multiple flowers have voice parts in this section, including swaying hydrangeas, red hydrangeas, and the Rose of Sharon, which is the Korean national flower, reappearing from the first section and children’s song.

FORSYTHIAS

(fluttering arms scattering petals across the map of Korea)

Azalea, you may powder!

SWAYING HYDRANGEAS

How many stars were there?

Yes ma’am

ROSE OF SHARON

A four-star general!

A three-star general!

A two-star general!

Over ten stars!

O lovely brides!

CHERRY BLOSSOMS

(in clusters, snowing)

Army

Navy

Air Force

Marine commanders

Rosy-posy!

They posed in front of the map

not an ordinary map

wires

flags

hills

mines

pajamas

SWAYING HYDRANGEAS

How many shots?

Yes ma’am

AZALEA

One shot!

One flash!

O beautiful picture!

O ring spots! (74–75)

“Hardly Opera” verges on the absurd, calling to mind an almost Disneyfied war of anthropomorphized flowers such as those in Alice in Wonderland (1951). Choi explains, “As a child, I believed that the people and things that my father photographed followed him and lived inside his camera. … Everything and everyone inside the Camera are mad” (49), echoing the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland who explains that he knows that Alice must be mad because she’s “here,” and “we’re all mad here.” As in a child’s mind, the differences between fantasy and reality, human and nonhuman, are blurred. The language and speakers of “Hardly Opera” recycle material from the previous two sections, so that this piece might be considered an operatic translation of the previous sections, which incorporate photography, news reports, correspondence, memoir, song, and other modes.

There is a path of media coverage throughout this book (i.e., the exploration of BBC coverage, 13), and we already know that Choi’s father was a photographer and the book contains pieces of journalistic language and photography. However, “Part II: Purely Illustrative” seems to be more specifically about the media message. The poems have headlines and columns like newspapers and seem to be rough translations of the same story, just as newspaper stories rework AP stories, or how translations are never “perfect” (30–32). Here is the first such faux article; in the book, the newspaper-like columns are fully justified:

NEW TARZON

GUIDED

BOMB HITS

BULL’S-EYE!

A secret new wonder bomb, the result of line. The Air Force refuses to give details

exhaustive testing and experimenta- of the Tarzon’s operation and range, but

tion, is dropped from a B-29 over a se- it hits the bull’s-eye as the bombadier

cret proving ground somewhere in the intended. That was a practice run. Now,

United States. At first the bomb, called in actual combat in Korea, the guided

The Tarzon, merely seems to fall, then as bomb seeks out the interwater struc-

if guided by an invisible hand, moves off ture of a dam vital to the Reds. Again a

to the right to follow the line below. At perfect bull’s-eye. Is the Tarzon in mass

the end of the line is the target, which production? Is it used regularly in Korea?

the bomb seeks out with an eerie, al- The Air Force doesn’t say. Still more sen-

most human understanding. Watch this sational films show the Tarzon seeking

performance carefully, for you are wit- out a bridge. Loaded with an atomic war-

nessing a new concept of modern war- head, the Tarzon could be the world’s

fare. Now the bomb holds fast to the most terrifying weapon. (30)

The headlines get scrambled and rework material from the first section of the book with dashes instead of punctuation, such as: “Like fried potato chips — I believe so, ut-terly so — The hugh-hush proving ground was utterly proven as history — Hardly=History” (32). If the first two stories are like slightly different newspaper or news radio coverage, the third story is like static between stations, recalling musical pieces that combine many sources for a cacophonic effect. On page 33 there’s another headline from the same “story world” as the previous three pages, but now it’s just a picture of two people on a motorcycle, on an “average day” perhaps, but with the title “again a perfect bull’s-eye.” Here, the bull’s eye may be the camera eye, but there’s a sinister hint from the previous three pages that the new Tarzon bomb might target and hit even a person riding a motorbike. By pages 35–36 there are no words, just two pictures of young girls. On the left there is a young Vietnamese girl holding a baby; on the right there’s a young Caucasian (American) girl holding a daisy. Because the right photo is from the infamous “Daisy Girl” commercial, there’s the contrast between what actually happened and what could have happened, between cruelty and privilege. We did in fact bomb Vietnam; no one dropped an atomic bomb on the little blonde American girl. Going over and over the same material with small changes mimics the way history is passed down or the way trauma survivors, such as children whose countries are overtaken by war, remember fragments of a traumatic event and replay them.

Writing a palimpsest of adult/military and child/play languages, of home/Korean and invader/US languages, calls attention to the way reading is a palimpsest, a collaboration between reader and writer. What I recall and research and what Choi writes become a pairing/dance — she leads, I follow, but I am in charge of my own feet and sometimes anticipate a different step or go off on my own. The author never fully controls the reader, and the more “experimental” the text (nonlinear, relying on skilled reading or special knowledge), the less control the author has. But that’s okay, because ultimately you’d like the reader to be thoughtful, to think for themself and draw her own conclusions, not to be led like animals to slaughter. This is not the BBC. Hardly War forces its audience to see multiple perspectives and hear multiple voices to derive an understanding of one of the US’s most silenced political theaters.