But there is a person there

A review of 'The Morning News Is Exciting'

The Morning News Is Exciting

The Morning News Is Exciting

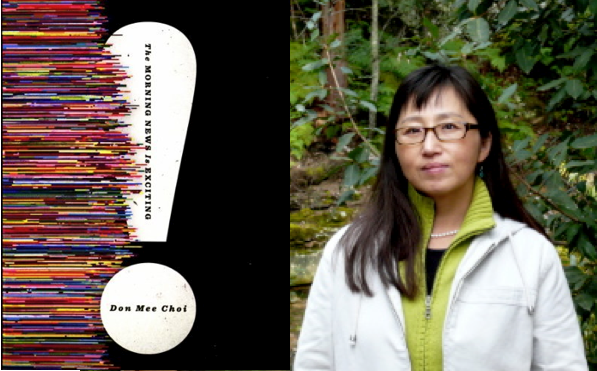

Okay, okay. I’ll admit it. I definitely judge a book by its cover. And Don Mee Choi’s debut, The Morning News Is Exciting, is no exception. The front cover sports a large, white exclamation point, penetrated by hundreds of colored bands that seem to explode from the spine. Yes, exciting, to say the least! Robert McKenna’s cover design is conceptually derived (the process is described in the end matter) and quite arresting, but I actually spent more time considering the back cover. Like any curious reader, I wanted to know what I was getting myself into, and who had recommended it.

Three customary blurbs stand in neat contrast to the dark background and declare a great many impressive things about the book. A quick scan of the names and some adept Googling reveals that three venerable scholars blurbed the book, including my friend and fellow poet Craig Santos Perez. Craig uses heady phrases to entice readers, such as “exiles against empire” and “demilitarizes, deconstructs, and decolonizes” to describe the work the book is doing. As generous and intelligent as he is, all these doctors and doctors-to-be raised my hackles a bit. Would this be another book that aims to do some conceptual task that, according to our academic sages, needs to be done? The poems, as described by others, seemed to be for something other than poetry itself. Well, of course, you might say. Perhaps, dear reader, I wasn’t in the mood for any upheaval, whether in the world of events or in the world of language. And so I began The Morning News Is Exciting, confident in my ability to simplify it into an overly vitriolic, self-pitying, poetic package of political hatefulness.

Ah, but Choi begins by making the reader bow and submit to her syntax. The collective imperatives jump off the page with what seems like a frightening and inappropriate whimsy, capped by the oft-appearing exclamation point. A string of absurd commands are delivered to us in nonsensical sentences to open the first piece, “Manegg” (which we later discover is a homophonic translation of Monchoachi):

At least sit well, we command:

Men say he but tally saying no, lame!

Who can respond. None say none. My wind, way low.

Lie, Egg, more lonely and bare, a callous lock.

Truly true Lass pause and care.

When I first read these lines … well, I was frustrated. Probably an immature and hasty response, but it’s true. Looking back on these lines after having spent time with the entirety of the book, I see so much more emotional heft at work, even in the lines’ weirdness. Who can respond, the poem declares, simply stating a poetic dilemma that many of us have grown accustomed to, but still experience as terrifying. The internal rhyming gives off the sense that someone is behind (or underneath, really) all this nonsense. And it’s not long until we encounter what appears as a reliable lyric speaker. The second section, “Diary of Return,” immediately anchors the reader in the familiar first-person narrative context that we crave:

arrived below the 38th parallel. Everyone and every place I know are below the waist of a nation. Before I arrived, empire arrived, that is to say empire is great. I follow its geography. From a distance the waist below looks like any other small rural village of winding alleys and traditional tile-roofed houses surrounded by rice paddies, vegetable fields, and mountains. It reminded me of home, that is to say this is my home.

Choi hands the reader over to a speaker, presumably from South Korea, who links the border between the Koreas with a metaphorical waistline, perfectly setting up the “feminist politics” which Craig praises her for on the back cover of the book. And she mentions empire. By name!

Ellen reads Choi (as part of Wave Books' Summer Reading Project)

The themes are evident enough: postcolonialism, violence (upon countries, upon women), domination achieved through language and syntax, and the book would not be without value if this were the extent of its merits. But there is a person there. There is a person there who breathes, who looks for home, who is sometimes many persons, but she is there. In “Diary of Return,” Choi embodies this female speaker in a series of vignettes about women who are presumably taken advantage of by American servicemen during and after the Korean War. In the following section, “The Morning News Is Exciting,” Choi takes a more abstract approach by comparing nations to girls:

Everyone is born wanted or unwanted, but some may be born exceptionally unwanted or wanted. A nation may be wanted or unwanted depending on what the other nation is thinking about.

And then later:

Something happens to the wanted girl. Nothing happens to the unwanted girl. The morning news is exciting.

If we read this with the earlier trope of a country’s waistline in mind, Choi not only illustrates the role of desire in invasion, but also how baser (literally, lower) desires can also be pretense for invasion. That is to say that the girl or country who is not desired for possession is still invaded and left for dead, “legs spread with the Cola bottle in her vagina and an umbrella up her anus.” And the speaker eventually admits this:

She has written that nothing happens to the unwanted girl. What an error. She’s an errorist.

Choi is often striving to resolve the difference between colony and home, wanted and unwanted, woman and nation, by interacting with “invader” texts, which are noted at the end of every poem: Foucault, Spivak, folktales, Dickinson, etc. The Morning News Is Exciting refuses to be either assimilated or impermeable and integrates these speakers into its collage of loss.

I find the use of Emily Dickinson particularly interesting. I mean, it’s a bit funny that Choi, who has heretofore been involved in translation of contemporary Korean poetry, would cling so tightly to a hermetic, dead, white woman. But she does. And Emily’s notion of the dialogical self is a fitting companion since it makes the self’s split explicit:

She went to Hong Kong in 1972. She was ten and knew only Korean then. She imagined there were two of her. She imagined me. I grew up in South Korea while she grew up in Hong Kong. I stay where I am.

The irresolvable distance surfaces again and Choi copes with it by speaking as two (sometimes many) girls, by writing letters between her selves, by transcribing diaries, poem-songs, and through a correspondence between three figures called Twin Flower, Master, and Emily.

It’s a bit disorienting, but once the reader has accepted disorientation as a possible aim of the book, The Morning News Is Exciting unleashes its power. The thirteen poems, which hover around eight pages each, flit from one form to another. If there are sustained queries, they are not borne through the means of a consistent tone, technique, or even the way the words look on the page. In fact, I would argue that the central question is: What is truly home? I am here but I remember there. The shifting form seems suited to Choi’s subject, though the book is dominated by prose blocks. And the self-contained poem-worlds offer the comfort of ordering devices (dates, numbers, headings) and footnotes, but these transitory anchors do little to prevent the poems from continually spinning their own “errors” and mistranslations into new injunctions for the reader:

Life begins now

Have no doubt

Have no door

This is not your fault

Run the rinse cycle twice

Don’t let the bubbles flow over

Life begins now

Have no doubt

Tea and Language

They say it’s a sensation

In her charmingly detached way, Choi moves from thing to thing with all the winsomeness and poignancy of a distracted child. The erratic mode seems second nature to a contemporary reader, possibly even calming. Despite her quick turns and changes, she frequently returns to basic symbols with a relentless obsessiveness that I admire in so many great poets. Sometimes these strange and simple things she carries through the book — moon, egg, star — lead her to stunning sentences that are not destinations in themselves, but are striking landmarks nonetheless:

Finally the child spoke. What is truly home? I am here but I remember there.