'A ceiling other than a sky'

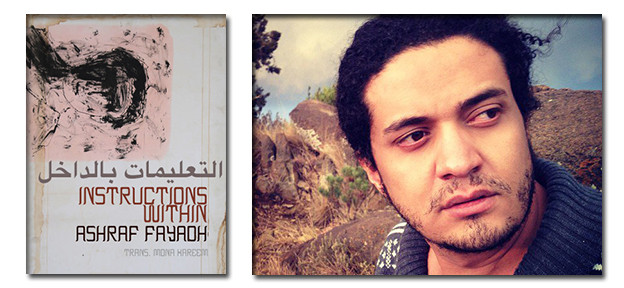

A review of Ashraf Fayadh's 'Instructions Within'

Instructions Within

Instructions Within

The outlines of Ashraf Fayadh’s life are clear enough: born in 1980 in Saudi Arabia to a Palestinian family, Fayadh published his book of poetry Instructions Within in Lebanon in 2008, was arrested in Abha, Saudi Arabia in August 2013, and was sentenced to death for renouncing Islam in November 2015.

How he came to be imprisoned is less clear. Fayadh’s arrest has been variously explained as the result of “a man he had argued with while watching a soccer game in a cafe,” “making blasphemous remarks during an argument in a cafe,” and “a single witness, who claims he had heard the poet make blasphemous comments at a cafe.” The differences are slight but add up to a conspiratorial air. Looking beyond more popular news, one isn’t quite surprised to find the mysterious patron actually a “rival” and Fayadh’s book actually “filled with love poems that describe his experience as a refugee from Palestine.”

These are odd refinements. The first uses a “rival” to demonstrate the malice of Fayadh’s oppressors, while the second confuses the subject of his “love poems” for descriptions of his “experience as a refugee.” Probably the writer didn’t mean that Fayadh loves the refugee experience, but the slip makes an easy target; it betrays a certain eagerness to draw sides with overdrawn enmity. Probably the writer just wanted to help the reader get to the point, but whose point? With The Operating System’s publication of Instructions Within,translated from Arabic by Mona Kareem (with Mona Zaki and Jonathan Wright), one can finally ask who and what were being stood for while Fayadh was trapped in his cell.

After his arrest in 2013, Fayadh’s situation deteriorated beyond Manichean pageantry into the smoke and mirrors of Saudi Arabia’s judicial system. Fayadh posted bail but was arrested again in January 2014, according to The Guardian, for “cigarettes and having long hair” after the police failed to prove that his poetry was “atheist propaganda.” The case went to court; the cafe “rival” was brought to witness, charging that Fayadh had “publicly blasphemed, promoted atheism to young people and conducted illicit relationships with women and stored some of their photographs on his mobile phone.” Fayadh repented and told the court that he was a faithful Muslim and that the incriminating photographs had been misappropriated from their professional context at Jeddah Art Week, where he and the women had staged an exhibition. In May 2014, Fayadh was sentenced to four years in prison and eight hundred lashes for apostasy. His lawyer appealed, and, almost a year later, the case was retried and Fayadh sentenced to death on new evidence of his blasphemy by poetry and the judgement that his contrition had been inadequate.

Then, in February 2015, a Saudi court overturned Fayadh’s death sentence for an eight-year prison term and eight hundred lashes instead. His punishment’s attenuation, however, is conditional to a public repentance the court is yet to receive.

This legal seesaw is certainly cruel, but is it unusual? Mona Kareem, Fayadh’s main translator for Instructions Within, thinks so, which should frustrate attempts to read into it a monolithic critique of religion or a regime. “I do not wish to see a fellow writer and friend being treated as just a case of ‘free speech,’ because that is demeaning to him and his work,” she said in an interview. “There is something challenging and evocative in Ashraf’s work that it bothered authorities so much, and the least we can do is to read it, allow it to travel, and engage with it.” Fayadh’s experiences are more complex than the versus-game of a pernicious religion and witnessing World Poet, and their exaggeration cheapens the life and the work. Fayadh goes to lengths to give his complicated identity complicated poetic expressions; the results in Instructions Within are complicatedly rewarding.

“Every loss / has a presumed existence … / every void / can be filled with void.”[1] This is the Third Rule of “Rules of Home,” which, with the other two rules, acts like a cipher for Instructions Within. Palestinian, stateless, immigrant, Fayadh was particularly vulnerable and so a target of the authorities in particular. He took up little space within the dimensions of Saudi Arabian identity politics, and could perhaps be disappeared discretely. First Rule:

Every home is safe … or in an ongoing war,

every home you step into without complaint

will remain in your heart …

Unless he is made upset by an alienation of the self

that strips him of value (100)

“Made upset by an alienation of the self / that strips him of value” is ponderous phrasing, but the shift from second to third person signals that alienation progressively. It would be easy to feel ironically above the baroque, plangent language if its registers weren’t changed so often, from the stiltedly epigrammatic to the sardonically confessional. See the Second Rule:

the alienation of a shapeless soul

is in direct proportion with your rants —

and with the illusion of stability,

lies about the weather,

the traffic noise,

and the percentage of nicotine in your blood. (102)

Though use of the first person is rare in his poems, Fayadh’s “you” seems autobiographical, like a distended “I.” On the one hand, this is the enormous pressure of his biography weighing on the work. On the other, it’s the swoops and dives of his art, grabbing the intimate from the alien: my reaction and relation to the beautifully limpid “traffic noise.”

Fayadh’s “void” is a composite of losses: the space of a homeland which never existed, his father’s death in 2015, foregone and expired romances, the cultural vacuum left over from Saudi Arabia’s addiction to oil (and America’s demand for it). These thematic voids he fills with symbolic ones, the recurring “crow, mosquitoes, money, bread, ceilings, walls, names, heart.” Only loosely are the images allegorical, the “ceiling” like “history” (“I am looking for a ceiling other than a sky, / sick of veiling my shameful history” [80]), the crow like Fayadh himself (“dark and rejected, with wings but incapable of flying,” says Mona Kareem in the Guardian interview), and so the poetry never resorts to polemic but remains obscurely personal. Saying one gets to know Fayadh over the course of the book would be disingenuous to his own conclusions. Seen from afar, from a religion or a nation or an industry, variegated individuals become instead like “lumps and meats of all prices”:

No difference … except for the ending H

and the opening A

No difference … except for breast size … and eye color

the diameter of hips and the length of organs

and the width of wombs … one or two numbers. (168)

Parodying the purveyors of wide-lens, manufactured salvation, Fayadh drolly writes in binary: “010001010110” (168). Elsewhere he fills the void with other voids, with ambiguities faithful to human complexity, so that gradually one is inculcated into his universe by a glinting constellation of symbols, collage, and verbal traces.

“Get creative at cursing your damned past” (138), and Fayadh’s mythology is up to that task. Whether he’s as ingenious formally is hard to say. Fayadh pulls from disparate sources, from the Quran to pop songs, and the free verse translation never misses, or changes, its beat. Perhaps this bespeaks his Arabic’s thorough aversion to a prosody, but I’m left wondering how or if the translators negotiated the competing diction and meters. The slangy “got” and severe “alienation” are both flattened into the same invariably various lines, and the reader loses grip on the context and connotations behind the words. What might be winking irony, a Marxist slant, becomes introverted, idiosyncratic, and occasionally abstruse.

Promotional biographies risk short-changing the work by a kind of extension of the Intentional Fallacy: Instructions Within is not a book whose importance is to be found mostly in the fact and circumstances of its existence, or their advertisement, without which the poems remain profound. This decoupling is maybe too hypothetical, but it helps one consider the ways in which Fayadh’s poetry is neglected by the attention given to his life. Instructions Within begins with a foreword that alludes to his “inner dialectic history” and “fundamental questions such as existence, identity, and the current moment” (vi). The latter begs the question of the “questions,” not least because “the current moment” isn’t specified, let alone what should be asked of it, and my small biography at the review’s beginning is only an attempt to piece together the “history” not authoritatively supplied by the book. While one can only respect the decision to present writers in their own words, especially in the context of Fayadh’s case, this prefacing buffers somewhat the impact of the words themselves. Fayadh, when he speaks for himself, can speak to all of us.