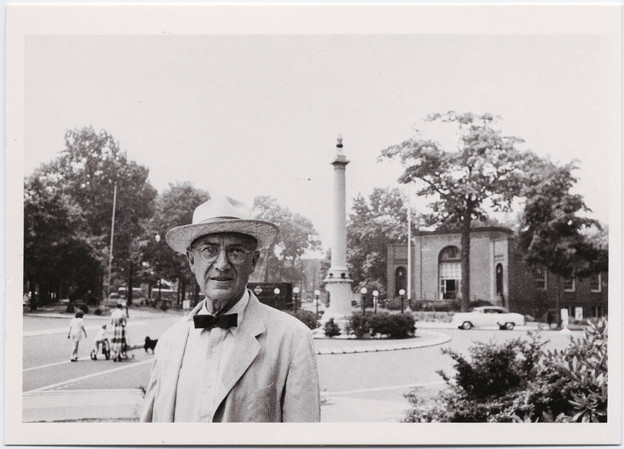

William Carlos Williams, 1952

William Carlos Williams

Indiana College English Association Conference, Hanover College, Indiana, May 16, 1952

Morning Program:

Lecture

“Smell!” (Al Que Quiere!, 1917)

from “Paterson Book II, iii” (‘Look to the nul’ to ‘endless and indestructible,’ 1948)

Evening Program:

“Portent” (The Tempers, 1913)

“The Botticellian Trees” (1930)

“Flowers by the Sea” (An Early Martyr and Other Poems, 1935)

“To a Mexican Pig Bank” (An Early Martyr and Other Poems, 1935)

“To a Poor Old Woman” (An Early Martyr and Other Poems, 1935)

“Pastoral” (Al Que Quiere!, 1917)

“To Elsie” (Spring and All, 1923)

“On Gay Wallpaper” (1928)

All poems except Paterson are included in The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Volume I, 1909-1939. All poems are segmented on Williams' PennSound page.

I inaugurate my column with William Carlos Williams: his contradictory restlessness for the modern makes him a perpetually dynamic site for thought. I chose this fiery document of late Williams for the productive tensions of his long-standing commitments encountering new historical particulars, especially between his Americanism and America’s emergent post-World War II international character.

Williams’ subject is the modern poem: “I’m interested in the modern poem, because I’m interested in you! And you are modern, you are alive now! And those are the things that poems have better be made of!” He insists the most important feature is measure, “that it isn’t the material […] it is the way you use that material and integrate it with your line.” He grounds his authority by an emphasis on the relation between the poem and modern society and by a rejection of the past: “[The way you use that material] comes of necessary changes of relationship of the elements in the poetic line and in all things else in our public lives, between the actual that we can directly experience about us, and the fanciful, the past, that we can’t achieve [….] All past verse is outmoded.” The stakes are thought itself: “The old measurements are so accepted that we have blinders on when we look at the newspaper […] it’s definitely ordered how we are to go about thinking of our lives [….] Poetry says that we must think about certain emotional aesthetic subjects according to form, and these forms must be so stated, must be measured iambic pentameters, they have to count syllables, and once we have accepted that, we’ve already committed ourselves to thinking about all sorts of other categories of materials under those lines, and it cannot be!” The consequences of thinking are manifest in the political situation: “In the arts a new world is being agonized for […] you know there’s something wrong […] the political situation shows it to us, there’s something fundamentally basically inhuman that sends our young men to war […] we know that it’s crazy!” Poetry is inextricable from the thinking of the age: “There are elements in various places which force us to go into wrong thinking. Now if the poem, if the fixity of the poem, subscribes to that wrong thinking, then the whole thinking about poetry is wrong! If the poem is so changed, is so altered, so remeasured, that it allows the mind to realize this is the right way, this is a broader way, this is not a constricted way of thinking, we have a chance then of thinking correctly about the world, and that’s the importance of the poem.” At the time of this lecture, America was two years deep in the Korean War, an effect of World War II less than seven years officially closed.

Williams constantly complements his position with a positive conception of America: “We are American! We are alive today! We want to read poems that interest us, that concern us, that are made of the structures of our lives.” Williams asks, “Can we guess what the outstanding feature of our 20th century will appear to be in the perspective of 300 years?” and suggests, “Our age will be remembered […] for having been the first age since the dawn of civilization […] in which people dared to think it practicable to make the benefits of civilization available for the whole human race.” He indexes the beginning of “this new social objective” of “welfare for all” far back to “the 17th century West European settlement on the east coast of North America that has grown into the United States, so that the United States, the advent of the United States has marked a change in the social history of the world, and you are Americans! You are the inheritors of that ideal!” and proclaims the “enormous benefits of the changes made by the discovery of America.”

Williams pairs this primordial moment by constructing an open form into the future for the efficacy of his prescriptions by insisting that “the way the world grows, grows slow, slow, slow changes” and casts a long wager that “maybe [the artist] will die, maybe it’ll be two generations before the rightness of the attitude toward his art is concerned.” The influence of his anxiety about an emerging generation of poets on his lengthy temporal perspective is suggested by comments such as “modern art is to set the pattern of our lives […] that will have to come out very gradually […] the young artist is very anxious to be recognized” and he also reveals a creeping conservatism and the constraints of his culture: “[The artist] can’t talk out loud, he can’t say things which would be too radical.” Williams’ selection of poems from his entire oeuvre, as far back as his first book, is his argument for the continuing relevance of the span of his work.

The subsequent American century and its wars just getting started in Williams’ moment necessitate the problematization of Williams’ recourse to an American historical singularity for Williams’ modernity to be seized to exceed the historical strictures of his thought. In “The Voyage of the Mayflower” in In the American Grain, Williams demystifies the Pilgrims’ “God” as their provisional apparatus for revolutionary expression: Williams’ Americanism for thinking toward welfare for all may be his. The contradictory American textuality of “To Elsie” and Williams’ matrix of the modern poem, modern society, and correct thinking are both more potent than and exceed Williams' undifferentiated American epochalism they are conjoined to here.

Each column I will post my next column’s recordings if you wish to listen to them in advance of my commentary. Next Sunday: LeRoi Jones, The Revolutionary Theater, 1965, and contemporaneous recordings of Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan at the Berkeley Poetry Conference.

PennSound & Politics