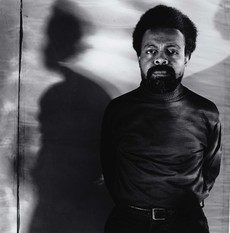

LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), 'Kenyatta Listening to Mozart'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

“Kenyatta Listening to Mozart” is an early poem of Amiri Baraka, then known as LeRoi Jones. It was published in a periodical in late 1963 and we’re assuming — for the sake of our discussion, which gets into some political history — that it was written earlier that year. Our recording was made at the Asilomar Negro Writers Conference held in the summer of 1964.

Mecca Sullivan, Herman Beavers and Alan Loney were our PoemTalkers for this quietly provocative — and perhaps brutally self-critical — poem. All four of us saw two political and aesthetic scenes, at least in the opening: “the back trails” of pre-Independence Kenya, and “American poets in San Francisco,” certainly standing in, at least momentarily, for Baraka’s two somewhat distinct concerns at the time: post-colonial radicalism, and the Beat aesthetic. One could say, not quite accurately — but helpful for starters — that this was a time when Baraka was making the move from his Beat nexus to world-conscious political heterodoxy.

Mecca and Alan discuss the apparently ironic juxtaposition of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Jomo Kenyatta, the Euro-trained anthropologist Kikuyu tribesman who helped lead the Kenyan negotiations with the British. Mecca wonders if, as elsewhere in his writing, Baraka is making Mozart as a cultural symbol susceptible to criticism in light of non-European struggles for basic freedoms. Is the “zoo of consciousness” the situation one finds oneself after one has separated and lost (“Separate / and lose”) or is it indeed endemic to the decision to cross aesthetics, share “in- / formation” (formalisms), and assimilate apparent opposites? Do we need to figure Kenyatta walking on the back trails, in sun glasses (a marker of “cool,” one of us says), wearing spats, in order to shake into being a real postcolonial anthropological notion? It’s not just “choice, and / style.” Well, it's that, but also more--for the “beautiful / categories” with which we discern what gets to be called beautiful are not necessarily things we should “go for.”

Mecca and Alan discuss the apparently ironic juxtaposition of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Jomo Kenyatta, the Euro-trained anthropologist Kikuyu tribesman who helped lead the Kenyan negotiations with the British. Mecca wonders if, as elsewhere in his writing, Baraka is making Mozart as a cultural symbol susceptible to criticism in light of non-European struggles for basic freedoms. Is the “zoo of consciousness” the situation one finds oneself after one has separated and lost (“Separate / and lose”) or is it indeed endemic to the decision to cross aesthetics, share “in- / formation” (formalisms), and assimilate apparent opposites? Do we need to figure Kenyatta walking on the back trails, in sun glasses (a marker of “cool,” one of us says), wearing spats, in order to shake into being a real postcolonial anthropological notion? It’s not just “choice, and / style.” Well, it's that, but also more--for the “beautiful / categories” with which we discern what gets to be called beautiful are not necessarily things we should “go for.”

July 30, 2009

In audio practice VI

Notes on Baraka recordings

My wife and I first met Amiri Baraka in November 1997, standing in line to get our tickets to a Betty Carter, Joshua Redman, and Maria João/Mario Laginha concert at New Jersey Performing Art Center in Newark. Baraka was directly in front of us! Both Amy and I had been readers of his work since college, were aware of his intensity, and struck up conversation with him. I explained I had been a student and friend of Ginsberg’s, and that I was living and working in Newark. He told us about monthly salons he and his wife Amina hosted at their home, Kimako’s Blues People, gave us his card, and invited us to come over — which we did many times during the next few years.