A short interview with Armand Garnet Ruffo

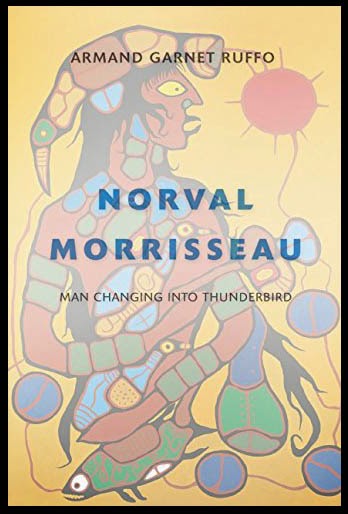

Armand Garnet Ruffo was born in Chapleau, northern Ontario, with roots to the Sagamok Ojibwe First Nation and the Chapleau Fox Lake Cree First Nation. Ruffo’s first collection of poetry, Opening In The Sky (1994), reveals an abiding interest in the complexities of Aboriginal identity in a multi-cultural society. His second book, the acclaimed Grey Owl: the Mystery of Archie Belaney (1997), is a creative poetic biography that further raises difficult questions about voice and identity, Aboriginal culture, human rights and the environment. Ruffo won the Archibald Lampman Poetry Award for his third collection of poetry, At Geronimo’s Grave (2001), in which he uses Geronimo’s life as a metaphor for resistance and survival. His latest writing project is the much anticipated Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing Into Thunderbird, a creative biography based on the life of the acclaimed Ojibway painter Norval Morrisseau, which was released in the fall of 2014 through Douglas & McIntyre; The Thunderbird Poems, based on the paintings of the artist, will appear in the spring of 2015.

In addition to writing poetry, Ruffo has written plays, short fiction and critical essays on Aboriginal literature, which continues to appear in literary periodicals and anthologies both in Canada and abroad. His numerous publication credits include editing a collection of critical essays, (Ad)addressing Our Words: Aboriginal Perspectives on Aboriginal Literatures (2001), co-authoring the “Indigenous writing “ entry for The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009) and co-editing the latest edition of Oxford University Press’ An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English (2013).

Ruffo returned to filmmaking after making experimental ‘video-poems’ in the 1980s and 1990s, and wrote and directed a feature film about the intergenerational impact of the residential school system. Released in 2010, A Windigo Tale won Best Picture at the American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco, and at The Dreamspeaker’s Film Festival in Edmonton, and went on to screen internationally.

Q: You’ve two new books on the Ojibway painter Norval Morrisseau: a creative biography and a poetry collection. What is it about Morrisseau and his work that first caught your attention?

A: First of all, Norval Morrisseau’s best work is magnificent and can speak to anyone. For someone of Anishinaabe heritage like myself, it is also a profound statement in that speaks to such issues as decolonization and survival without necessarily being overtly political. When I was initially asked to write something for the National Gallery of Canada’s Norval Morrisseau “Shaman-Artist” retrospective catalogue, I was initially hesitant. As I say in the introduction to the biography, Man Changing Into Thunderbird, like many people, I had heard about him, but I really didn’t know much about him or his art. Right from the beginning, then, I knew that if I took on the project I would have to learn a great many things, everything from visual art history, aesthetic theory, Ojibway material culture, the Ojibway oral storytelling tradition, about the Ojibway “Manitous,” etc, and I knew it would be daunting. Then, without trying to overstate it, I had a kind of epiphany where I suddenly realized that I had to do it. I guess I realized how important he and his work are to Anishinaabe people, and, frankly, he had a very interesting life, and the more I learned about it, the more I wanted to know. I also have to add that my own Ojibway mother was born about the same time as Norval and into more or less the same circumstances so that connection existed, and it also made me want to know more about him and his times. Furthermore, the NGC ended up giving me carte blanche as to how I wanted to approach the subject, which also opened a door for me, and which I found both intriguing and challenging.

Q: What was it that made you decide to approach the project as both a creative biography and separately-produced poetry collection? Was it simply a matter of different material speaking to you in different ways, or was it more complicated than that?

A: Yes, the biography was really intended to document Norval Morrisseau’s life and artistic process, while the poems were a natural and spontaneous response to the paintings themselves. That said, I only started writing the poetry after I had done some of the research into Norval’s life. So while the poems come right out of the artwork, many of them include biographical details. In other words, I let the paintings guide me without trying to censor what they wanted to tell me. My original idea was to include a few poems in the biography. Because the paintings are dated, I thought I would likewise date the poems which would be a good way to let the reader know where they are in the text. The poems would serve as a kind of marker for the reader. However, as I plunged into Norval’s art, more and more poems came. I did end up choosing a few of them for the biography as planned, but by the time I finished writing and editing, I also had enough for a stand-alone collection. Hence, the two books.

Q: Much of your published work so far has focused on Aboriginal cultural identity and politics, with research featuring heavily in more than a couple of your projects. With five published books over the space of twenty years, how do you see your working developing, and what do you feel you’ve accomplished, or not accomplished?

A: Good question. Every writer has to find his or her material. Sometimes the process comes quickly sometimes it can take years, maybe a lifetime. For me, it came rather quickly – which isn’t to say the writing came quickly. While I was in Toronto going to university I happened to take a writing class because I needed an elective. We were given a writing assignment, and I started imitating the poets and writers I was reading at the time, mostly British and popular American writers. It sounded false because their reality had nothing to do with my own. Then one evening I was visiting my Ojibway grandmother (who was living with my aunt at the time in Toronto), and she read me some of her poetry. It sounded archaic because she was very influenced by Pauline Johnson. I had no use for the form, but the content struck me. I then went back to school, and I started writing about my reality in the north. Suddenly I had my material, and I guess after all these years in one way or another I’m still writing about it. You’re right, I have the books, and they are pretty much concerned with some kind of Indigenous reality here in Canada, because, simply put, that’s what I know and that’s where my interests lie. I’ve managed to expand the themes over the years – for example, my feature film is about the intergenerational impact of the residential school system – but I’m essentially still roaming around in the same forest. And to be frank, because of the long history of imposed silence on Indigenous peoples in this country—here I’m referring to disempowerment, broken treaties, languages being banned, etc.—there is more than enough material to keep me going. I’m not sure if I’ve answered your question, but I will add that form and aesthetics also interests me, which in part got me interested in writing a feature film, and I would like to continue to experiment with these concerns as well.

Q: There have been a number of writers over the past few years work more overtly about and against the imposed silence you speak of, utilizing writing as a form of active resistance: Annharte, Liz Howard, Thomas King or even Shane Rhodes’ 2013 collection, X: Poems & Anti-Poems. What I find interesting about your work is in the way you seem to, instead of pushing a resistance (as John Metcalf would have called, “kicking against the pricks”), your writing and editorial projects work to articulate a presence. Has this been a deliberate effort, or even a conscious one?

A: When I began writing in the 1980s my work could be classified as “protest” literature. I mean it is impossible to be an Indigenous person in Canada with a sense of history and not be angry at what has gone down since contact: systematic disempowerment, land confiscation, unjust laws, languages and ceremonies banned, violence, you name it. However, what I soon realized is that if “oppositional” (as Thomas King calls it) writing is all one focuses on, it is inevitable that one will write oneself into a corner and ultimately end up in silence. I have seen it happen. Someone comes out with a first book that is protesting the treatment of Indigenous people, and they don’t write anything else. Of course there are exceptions to every rule, but that said, if one doesn’t move on, one ends up generally repeating oneself over and over again. For me, after my first book (and many poems that never got published), I wanted to do something completely difference. I was fortunate in that I had always wanted to write about Grey Owl because he had lived with my grandmother’s parents in northern Ontario, but in looking back I think writing about him allowed me to break the protest mould so to speak and move on, and because it was a “big” project, it also gave me the confidence I needed to continue writing (—remember, unlike today, there were very few Indigenous writers for role models—), to write my feature film, for example. Jump ahead twenty years to the two Morrisseau books, and I would say that you are right on when you say they “articulate a presence.” Both books move from focusing on our “oppositional” relationship with the dominant culture to being Indigenous centered texts, focusing rather on Ojibway epistemology, art, and aesthetics. But to answer your question directly: when the opportunity to write about Norval Morrisseau landed in my lap so to speak, I immediately saw it as a challenge for this very reason. I knew I would have to learn tons of stuff, but I also knew that it would lead me into “new” territory, which is very ironic because I was really going back into the “old.” And while these works do “articulate a presence,” I still think they can still be considered “resistance literature” (which I’m proud to say) in the broadest sense of the term, because by articulating this presence, the writing flies in the face of the “vanishing Indian” stereotype and challenges the continued colonial domination of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Q: Did the experience of having your book Grey Owl adapted into Richard Attenborough’s feature-length Grey Owl (1999) provide you with any insight into the work? Was it a positive experience, and were you consulted at any point through the filmmaking process?

A: As Woody Allen said about fame, we get about 3 minutes, and I guess I’ve had mine. I was escorted through the barricade and got to stand beside Attenborough while he was shooting the film. But seriously, aside from meeting Richard Attenborough and Pierce Brosnan, I didn’t have anything to do with the movie, which really disappointed me when I finally saw it. But I should have known, because when I was chatting with Brosnan during the shoot, he said he wished the script had been more like my book, in which Archie Belaney, Grey Owl, is presented as a troubled figure. The movie is really a whitewashed, Hollywood version of him. In hindsight though, it did inspire me to make my own feature film, A Windigo Tale. After meeting being on set, I went on to take some film workshops with Canadian filmmakers like Deepa Mehta. And although it took me 10 years to make my own movie, which is crazy when I think about it now, it was an amazing experience despite all the trials and tribulations.

Q: Much of your published work focuses around the stories, and even myths, of real figures, from Grey Owl to Geronimo to Norval Morrisseau. What is it about writing with and around the materials of real figures that attracts? Is there a particular freedom you’ve noticed that comes with writing another voice, allowing you to speak to your own concerns, or do you attempt to keep to the voice and concerns of your individual subjects?

A: First off, I guess I don’t consider my own life all that interesting compared to the people I have written about, and although I do write about my own experiences, I’ve tried to be judicious, because I’ve found that a lot of contemporary writing has turned into a kind of “navel gazing”—blame it on the “confessional poets”—which I personally find rather boring, unless the writer/poet really has something interesting to say. So many writers repeat themselves over and over again, and I guess it’s one of the things I fear about my own work. Second, I have always been interested in history because from an Indigenous perspective, history is right in front of you. And, finally, I think there is something liberating in writing about someone else. And, yes, certainly you don’t want to “break out of character,” but at the same time you are writing out of your own sensibility, and even experiences, so really you can’t help but write out of your own concerns.

Q: I’m curious about your influences, both early and current. You mention your Ojibway grandmother as someone who influenced some of your early writing. When you were just starting out, what was the writing, whether positively or negatively, that pushed you to write? What are the works that, early on, that might have informed the what and the how of your work?

A: When I moved to Ottawa from northern Ontario to work for the Native Perspective magazine in 1979, one of the first things I did was publish my Ojibway grandmother’s poetry. So, yes, she wrote poetry, and told amazing stories about her life, and the life of our community, in and around Biscotasing (northern Ontario), but I can’t say she was an influence initially. She wrote in the style of Pauline Johnson, the 19th century Mohawk poet, which I found very archaic to my teenage sensibility. My earliest influences were mostly songwriters like Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Gordon Lightfoot and Leonard Cohen. Cohen was probably the most influential, not because of what he was writing about, but just that he was actually writing books. I discovered from the liner notes that he wrote poetry, and I began to read his work. When I later went to York University I tried to imitate him, and the others I was now studying, Purdy, Atwood, Ondaatje, etc., but the writing didn’t go anywhere because my reality had nothing to do with theirs. Then one day, I was visiting my grandmother and she read me one of her poems about “the north country” – as she called it, and I saw through her style to the content, what she was actually saying, and I went back to York and started writing about my reality in the north, drawing on my Aboriginal heritage. Then when I moved to Ottawa, I got introduced to Aboriginal poets like Duke Redbird, Rita Joe, George Kenny and Wayne Keon through the Native Perspective magazine. As the Okanagan writer and scholar Jeannette Armstrong has eloquently written, it was these poets who spoke to her, and they spoke to me. Then in the early 90s, I went to the University of Windsor, where I studied with Alistair McLeod. So I guess there’s been a lot of influences along the way. What I remember about York was studying with Eli Mandel who was a prominent Jewish-Canadian poet and critic in the 1970s, and it was through him that I really got introduced to the Canadian literary scene. And I was taking courses in British and American literature as well. A door had been opened and I was reading widely, anything and everything. I should add that Mandel was very encouraging when I started to write critically about the “Indian” stereotypes I was reading by non-Indigenous writers. As I said, I only started reading Indigenous writers when I later moved to Ottawa. There just wasn’t the kind of Indigenous literary scene there is today.

Q: Who are the Aboriginal writers you’ve been reading that you think deserve a wider audience? Who are you reading now?

A: I’m one of these people, probably like you, who has a number of books on the go at the same time. I just picked up a first novel called Rose’s Run (Thistledown) by Plains Cree writer Dawn Dumont. She’s a comedian, actor and a playwright so I’m looking forward to it. I need a laugh, especially after working my way through Joseph Boyden’s The Orenda (Penquin). On the academic front, I’ve been reading the essays in Neal McLeod’s edited Indigenous Poetics in Canada (WLP). It’s refreshing to have such a book because to date Indigenous literature has been used by academics to examine predominantly socio-political issues—right now it’s all about “reconciliation”—as if that’s all Aboriginal writers think about, and formal and technical concerns don’t matter. In any case, I also read non-Aboriginal writers; I was given Ottawa writer Frances Itani’s novel Tell for Christmas, and I’m looking forward to it as well. On the poetic front, a friend of mine, the Irish poet John Ennis sent me his latest book, A Pullet For Jack (Bookhub), which I’m currently reading, and while doing a reading at the Toronto International Book Fair in November, I picked up Garry Gottfriedson’s Chaos Inside Thunderstorms (Ronsdale). And finally, while in Ottawa, I was given TREE poetry’s Twenty-five Years of Tree, which I’ve also been dipping into from time to time.

As for a poet who I think deserves a wider audience, I am a big fan of Philip Kevin Paul from the Saaanich Nation of Vancouver Island. His poems are quiet, insightful and honest. He’s not trying to be hip or popular, write in the latest fashion, and I think for this reason he’s remained under the radar for most people. And he’s not prolific. His last book Little Hunger came out in 2008. I’m looking forward to something else!

Some notes on Canadian poetry