Shannon Maguire: Three new poems

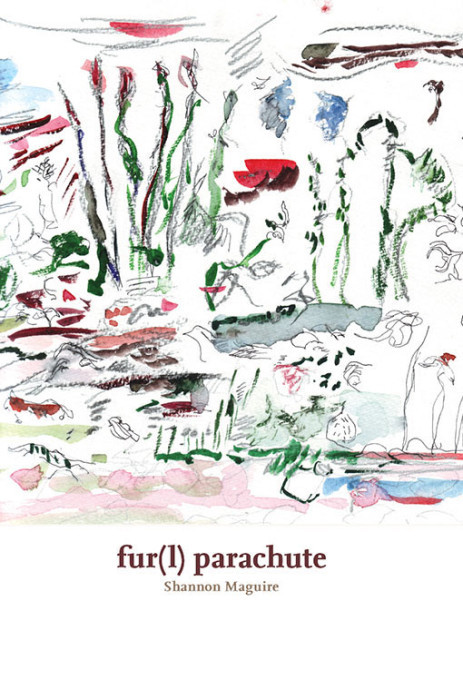

One of only three Canadians (along with Vancouver poet Kim Minkus and Toronto poet M. NourbeSe Philip) included in the premiere edition of the annual Best American Experimental Poetry (Omnidawn, 2014), Toronto poet Shannon Maguire’s first collection, fur(l) parachute (BookThug, 2013), a collection Eric Schmaltz referred to in his Lemonhound review as “a shining debut,” was shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and the Manitoba Magazine Awards in the category of Best Suite of Poems. Originally trained as a playwright, having studied at Montreal’s National Theatre School of Canada in the late 90s, her poems are constructed across a wide, even theatrical canvas of narrative, bricolage and collage. As Schmaltz writes:

The poems speak to their past — a one thousand year old surrogate — while weaving into it cultural allusions and anachronisms — Shakespeare’s Ophelia and Mae West alongside more contemporary references to fly fishing (as seen in the section entitled The Midwive’s Hands) and (perhaps even) Canada’s own Tim Hortons coffee chain “roll up the rim/ en spies de” (4). Maguire then pushes us further into the future exploring animality, desire, and technologic. There are no boundaries to Maguire’s imagination — time is one, all subject matter is relevant.

Her chapbooks include the bpNichol Chapbook Award shortlisted Fruit Machine (Ferno House, 2012), as well as Vowel Wolves and Other Knots (above/ground, 2011) and A Web of Holes (above/ground, 2013), and she has been collaborating in experimental translation with Finnish poet Vappu Kannas, with a chapbook of their recent work, As an Eel Through the Body (One Night Stand) forthcoming from Dancing Girl Press in fall 2015. Her second poetry collection, Myrmurs, also appears this fall from BookThug. In an interview posted at The Toronto Quarterly, she writes: “A great poem is one that seduces the reader into adopting a mode of thought that previously registered as noise.” The poems in fur(l) parachute expanded out from the Old English poem “Wulf and Eadwacer,” as she explains in her endnotes:

The Old English poem Wulf and Eadwacer appears in the 10th century Exeter MS between the elegies and the riddles. There is no consensus as to its meaning, origin, or even to genre. Some see it as a riddle, others as an example of woman’s lament, and yet others in the broader tradition of the elegy. It is a formal oddity, being one of only two extant Anglo Saxon poems having a refrain (the other poem is Deor), and being one of the few extant Anglo Saxon poems to be written from the point of view of a woman.

fur(l) parachute is a work composed in six sections, some of which fragment into subsections, even as the poems themselves fractal, breaking down pieces into phrases, words and singular letters. With words and lines crossed out, individual letters floating across an open space of the watery white page, or reduced to the syntax of a howl, she utilizes the thousand year old poem as a bouncing-off point, unafraid to explore and expand sound and stretched meaning, inference and the shape of the page. Opening with a reworked version of the original poem, “a transformation from Old English,” the collection continues into sections for each of the poem’s characters, reworking her own version of “wulf & eadwacer” into something far greater. Further in her interview in The Toronto Quarterly, she writes:

fur(l) parachute is all in the translation. It works in multiple registers, and multiple times, but has no message in the conventional sense. Because of this, it is highly political, that is, it acts on objects in the political realm. It is utopic in the sense of engaging in the slippage between no place and happy place. It attacks the form itself, rather than the content of its Old English “original” poem “Wulf and Eadwacer.” And I engage (and challenge) OE textuality right down to making connections between wyrd (fate/textuality) and mathematical knot theory…

Including references that include “a wetlands Ophelia,” Shakespeare’s Ariel and Mae West, fur(l) parachute is rife with stories and myths, weaving in threads from other tales. Her poems shift, shimmy and rage, and push a constant, pulsing rhythm that twists expectation, genre and gesture. Rich with research, Maguire’s poetry has a voracious curiosity and exploration into language, translation and history, allowing voice to a series of women too often muffled, muted, dismissed or altogether voiceless. In fur(l) parachute, Maguire transelates (in the Moure sense) Old English and Middle English into language poetry, composing a new kind of becoming and emerging from the dark, deep woods. Speaking of her use of texture and sound in her Open Book: Toronto “Great Canadian Writer’s Craft Interview,” conducted by Erin Hanley, she wrote:

I often work vocally, building sounds, images, and rhythms out loud with my voice. But I am terrible at the pronunciation of dead languages. So when I was writing fur(l) parachute, I did a lot of fighting with my tongue. I knew intellectually what it was “supposed” to sound like (we don’t really know what Old English sounded like!) but the sounds I actually made didn’t really conform. So then I realized that this dissonance could be creative in itself. But it’s a little unnerving to go there in front of an audience. And then poems like “spill” pose a different challenge because it was written as a sound poem for two voices. I was lucky to get to actually perform it with Lee Skallerup Besette out in Kelowna last summer. But I basically put her on the spot! The reading was organized by Karis Shearer as part of “Poetry Off The Page” and I walked in and said to Lee, wanna read with me? And she said yes! It was really fun and Lee was brave and such a sport to indulge me. Next time I perform it with another voice, I’d like to rehearse a bit.

Her second collection has yet to see print, but her current work-in-progress, from which the poems below are taken, is “Zip’s File,” the third book in what she calls her “medievalist trilogy.” In an interview forthcoming at Touch the Donkey, she discusses the trilogy as a whole, writing that:

all three tease out one aspect of a larger question that I’ve been trying to work out, which is something like: How has Western culture influenced the literary, cultural, sexual, and political bodies that we’re living inside now and what role did/does the English language play in transmitting, producing, circulating, and maintaining gender, racial, and sexual difference? And how does change come about, linguistically, socially? Since (dammit Jim) I’m a poet and not a social linguist, my research has to be conducted and reported in poetic form ...

Jumping from the poems in the first collection to a short selection of work-in-progress pieces from the third might be considered jarring, but one suspects the three collections exist less as a linear narrative of works than an open-ended montage of structures, akin to the open-ended bonds that connect the works that Robert Kroetsch corralled into his Completed Field Notes: The Long Poems of Robert Kroetsch (University of Alberta Press, 2000), or bpNichol’s The Martyrology. In both of Maguire’s works — first and third — exist her obvious love of language and disjuncture, researches into Old English history and legend, and the stretch across a wide canvas.

Before Merlin

be disnatured;

looking forward unstuckwhen nature over us mounts

between the oppositions of our various sensesevery thing that nature can mess against

degenerates, when left to ourselveswhen “a” is hormoneously combined with “us”

she says: “alas, a lass Nature!” you use me so much trouble!You have brought many a good man-low

you are without a doubt: we’re all rotten”

stockyards and packing houses

Berries, bird, blind date, carry a torch, cash, coffin varnish all in a rush. Say it’s 1922. Say we’re Kate and Heloise. Heloise is dolled up; Kate is Daddy-Dame. Slaughter house savvy, Kate wears a falcon’s beak in her bra; Heloise has a small collection of explosives under her boarding-house floor.

We meet in a meat packing plant: cattle, sheep, poultry. Your kitchen is small, but well-hung with herbs. The night clings to us like butcher-paper. You heave the squealing, screenless window. See the world! clouds crack throw figure in face; a cat. You say, I intend to hunt again!

You say, company is master, you good, so together, sweet man-wish. All the West End bachelors throwing the daintiest pebbles onto the linoleum could not stir us.

To be whipped … now; yet again; light on a fit. Come! freeze to my teeth, lips. Heavy chance. Take cold. Holla ho! One chestnut fears none. Mutter, I’ll buckle her!

The landlord knocks. He knocks again. He won’t shut up. Says you, you’re spifflicated, so scram, mister. What’s eating you?

Shut the window.

Chicago May’s Plum

The Deer is decked in hurricane oratory.

The Deer is decked in hurt orbit.

The Deer is decked in huntsman’s obituary.

The Deer is decked in hurdle oblivious.

The Deer is decked in url, Horatio.

The Deer is decked in hurry or.

The Deer is decked in hush orchid.

The Deer is decked in husk orchestration.

The Deer is decked in hustle ordeal.

The Deer is decked in heaping ovation.

The Deer is decked in hunter orange.

Some notes on Canadian poetry