Reading Yousif M. Qasmiyeh's 'Writing the Camp'

The tender, raw poetic investigations in Yousif M. Qasmiyeh’s recent Writing the Camp (Broken Sleep Books, 2021) conceptualize a theory of the refugee camp as archive, taking as local frame Baddawi Camp in North Lebanon, where Qasmiyeh grew up. Qasmiyeh’s project moves with “the intention of co-seeing in writing what would otherwise reach its end without being remembered as the lived.”[1] The collection interrogates the ability to see, sensitive to the question of who sees. Rather than recover a disappearance, it seeks to accommodate absence within language and on the page. I begin this Commentary series with a reading of Writing the Camp because it holds at its center the possibility, the expectation, of nonarrival. The camp is a space of continuous, tangible transition — ‘the camp is time’ — and becomes for Qasmiyeh a concentrated site of theorizing the poetic archiving of disappearances, spatially spanned.

Baddawi Refugee Camp is the delimited area under consideration in the collection, even while the definite article, the proper nouns, the process of naming, and the tether between language and place remain entangled and fraught. Baddawi Camp was established in the mid-1950s as a site for Palestinian refugees by the UN Relief and Works Agency. The one-square-kilometer camp has grown vertically and is host to newer arrivals, currently predominantly Syrian refugees. In the poem “Writing the camp”: “The camp is never the same albeit with roughly the same area. New faces, new dialects, narrower alleys, newly-constructed and ever-expanding thresholds and doorsteps, intertwined clothing lines and electrical cables, well-shielded balconies, little oxygen and impenetrable silences are all amassed in this space” (59). This is a book that is defined by the body’s movement around this environment: the threshold, the cemetery, the signpost. The body of the refugee becomes sensor whose touch, and whose naming of that touch, is what accrues the archive and navigates questions of witnessing a space.

Qasmiyeh’s poetry is essayistic, composed of intimate, minimalist philosophical notations that ride the boundaries of hybrid forms. The collection is an integration of critical conceptualizations and methodologies of the camp as archive that Qasmiyeh has developed across a range of academic, literary, and experiential settings, and which arrive to poetry as a distinctive form to convey the transitory. “The camp has never been entirely a place, but a multiplicity of entwined histories and times” (52), Qasmiyeh writes, as he uses a host of techniques to communicate the camp’s transience formally. Many of the poems contain masterful turns; we end up very distinctly not where we began because of a crucial moment of rupture between departure and arrival. The turn is often produced by the sudden recognition of multiple, concurrent senses of time, as if a piece of news occurring elsewhere has just intersected with the site of the poem. In the sparse and arresting poem “Mother,” Qasmiyeh writes, “She will die soon / Unless she has already / Without telling me.” At the poem’s open, the “soon” situates us on a linear scale that includes a distinctive futurity, one that may have even already come to pass, unknowingly. A turn lifts us out of the layered binaries of the first stanza: “This is how she normally dies / Discreetly and alone” (11), upending and multiplying expected chronologies.

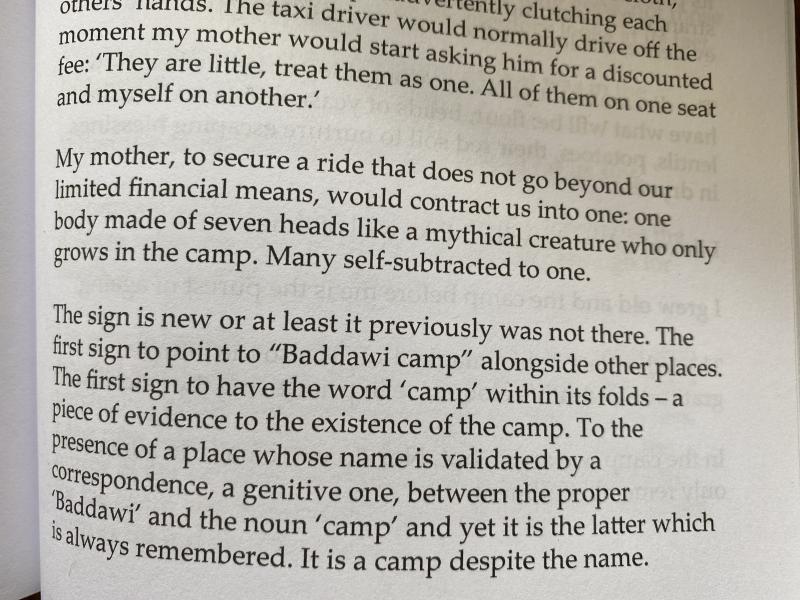

The line “without telling me” can be read as a crux of the questions of Writing the Camp. What is the relationship between happenings in time and telling about those happenings? Likewise, what is the relationship between navigations of space and telling about those navigations? Qasmiyeh depicts a spatial example of this question:

This last sentence implicitly conveys naming as a process against impermanence. The naming of the camp visually on the landscape through signage invites a parallel critique of the naming of this space in verse. Qasmiyeh questions what it means for a place to be named: not just in comparison to other names (historical names, fraught names) but in relation to not having a name and not being written.

Still, naming only seems to harken arrival. In the poem “With a third eye, I see the catastrophe,” Qasmiyeh writes, “In the camp, we arrive not. Nor do we remain” (114). A multilingual poet, teacher, and scholar, Qasmiyeh takes the camp as site for evidencing the myriad ways in which nonarrival takes place within language. The trembling nonarrival of language into place, into mouths, points to a concrete impulse of this project: a resistance of the instrumentalization of representations of refugee experience. Throughout the collection, foreigners and anthropologists are depicted coming into the space of the camp, while the poems insistently reject their demands that the camp be made intelligible. A poem titled “Anthropologists” imagines, “Sometimes I dream of devouring all of them, and just once with no witnesses or written testimonies” (17). Instead, the poems unravel their own critical apparatus for the body, archive, and time. Against the sensationalized, the poetry rather emerges “without delving deeply into the personal but hovering above it.” “Hovering over,” in a nonarrival of the intimate emerges as a way of seeing, and it is a different “hovering over” from surveillance; it is a tender hover, a separateness which allows breath, a different gaze.

Qasmiyeh describes that processes of writing the camp: “remind the camp’s inhabitants that it is their right to write what is deemed theirs in the spatial and territorial sense, even though such markers are never conspicuous.” These philosophical considerations of subjecthood and agency in narrative take tangible shape in Qasmiyeh’s role as writer-in-residence of Refugee Hosts, returning to Baddawi Camp to lead writing workshops in conjunction with Pen International and Stories in Transit. The questions that ground the collection are at once pertinent questions of how poetic production is organized: “Who writes the camp? Who traces the camp’s evolution into (a) space? Who demarcates its limbs as they retreat internally in order to accommodate more refugees?” In this passage Qasmiyeh refers to the camp’s transition as current host to predominantly Lebanese and Syrian refugees, a process studied and documented within Qasmiyeh’s collaborative work on refugee-refugee hosting.

These questions of witnessing are pared down, and their antidote emerges simply: a poetics grounded in the sensing body. “As we walk, we remember” (104); the “we” reaches widely, but at once circumscribes the speaker(s) within the circumscribed space addressed: “we” refers to those whose bodies are present to archive the space. In investigating the relationship between body and place, Qasmiyeh questions what it means to “take in a place” as corporal archive; to carry place in the body, and for the body to “be made out” / “make it out” of a place.

The body takes samples: “Whatever state it is in, it is that that carries all states to the threshold” (24). Walking, and touch, happen independently of the naming of the space and before the naming. The poet depicts holding his mother’s hand in his own, teaching her to write her name. In this image, the body’s archive comes first: “The unseen — that is the field that is there despite the eye — can only be seen by the hand. After all, the hand and not the eye, is the intimate part” (62). The hand is what writes, and the hand, and not the eye, is what names in this collection.

At the same time, sensing with the body splinters the flesh. The body of the refugee is at once doubled, borrowed and never arriving; an avatar, a representation of a deity — “In asylum, we borrow our bodies for the last time” (25). These duplications and shadowings of the body at the threshold are investigated through parsing layered meanings of key terms with both intimate corporal and violent state connotations: fingerprinting, invasion. Keywords are used throughout the collection as sites of memory with multiple imprints — absence, time, return, revenant, archive. The touch of the body at the threshold, carrying states, is only bearable through the body being split and doubled, articulated through the splitting of word meanings. Like Solmaz Sharif’s use of keywords from the Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms in Look, the body in Writing the Camp makes it through the threshold by splitting meanings. In “Fingerprinting,” “She did to me what a friend would normally do for a friend or a lover for another lover — she held my hand very tightly” (43). Meanings nest inside of words used violently, nexting towards a different future.

Disappearances in this collection appear when doubles are propelled into one being: a body, word meanings, tenses of time. Qasmiyeh asks, “But how could this disappearance be reached in the first place? How would an absence — with the bare minimum of a body — be evaluated and sensed? // This might lead us to presume that the journey is that of a being whose main objective is never to arrive” (27). This understanding of sensing disappearance within a trajectory invokes Qasmiyeh’s work following Derrida, that “The archive is always written in the future” (62). Qasmiyeh’s work is a component of the project Imagining Futures through Un/Archived Pasts, whose premise is that “archives are negotiations about visions of the future — whose story will continue to be told and how, and whose silenced — and that these become acute in moments of post-conflict, displacement and reconstruction.” In this way, Qasmiyeh shows, archiving by sensing a delimited place and “co-seeing in writing” are processes that can make claim towards future space that has always not yet arrived.

-

This Commentary will feature an upcoming conversation with Yousif M. Qasmiyeh. We welcome you to send questions that you would like to ask the poet, and we will fold them into our conversation. Email hspicer@epcc.edu.

Architectures of Disappearance