“Deep alongsideness”: translating the city in parentheses, quotation, and book objects

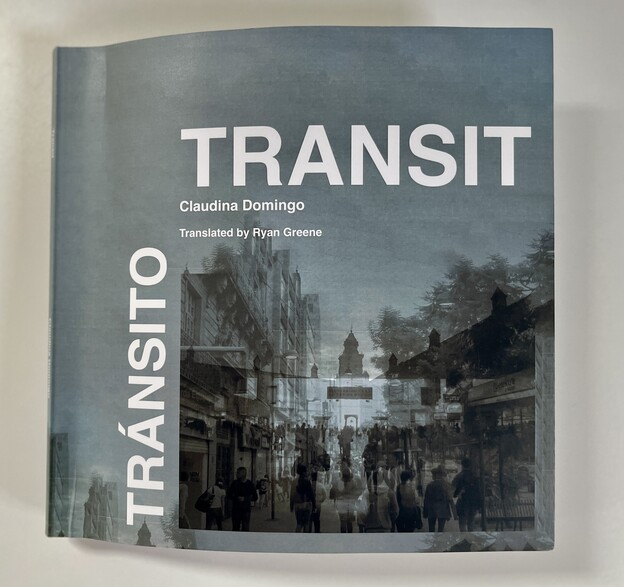

A review of Claudina Domingo’s ‘Transit’ translated by Ryan Greene (Eulalia Books, 2024)

Claudina Domingo began the poems in Transit by walking 24 routes through Mexico City and registering the accretions of those experiences. First published by the Mexico City-based editorial Tierra Adentro in 2011, Ryan Greene's 2024 translation with Eulalia Books puts the book in conversation with poetic texts in English interested in spatial practices in the situationist lineage. Domingo’s routes chart, as Greene describes, “a path past ‘half-chewed’ churches, through churning markets, and under rain-drenched awnings” as the poems trace onto the page an accumulated streetscape of Mexico City’s pasts and presents.

Domingo instigates the question of how to mark on the page that which the poet simultaneously experiences in the cityscape. But what does it actually mean to convey a city’s “500 years of collaging over itself” in the space of a page? (125) What resources might the poet draw on to approach such a task? Greene’s capacious translations wing this question into entirely new spaces, becoming a question pertinent to bilingual publication and to the relationship between a book and the space it is within and about. Greene’s eight-year project of translating Transit through multiple experimental forms creates a remarkable space, a playground for deep thinking about translation, materiality, place, and their relationships to each other.

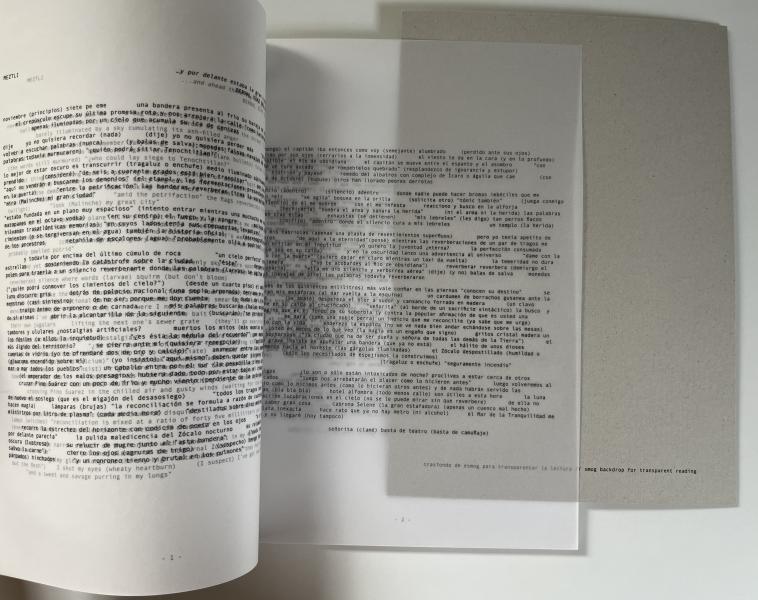

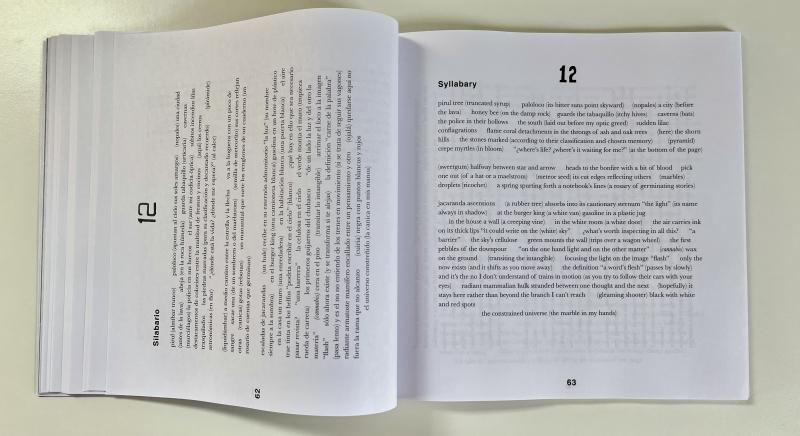

Transit is written in long, multi-line phrases ordered throughout with spaces, quotation marks and parentheses, and punctuation becomes the predominant resource Domingo uses to convey spatial collage in text. In translation to English, word orders and lengths of lines shift; the translation bulges or condenses distances between punctuation, but the punctuation itself persists as given form. The reader enters a punctuated made-space which constructs an infrastructure between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of translation, even while word-inhabitants move in an out, constructing insides and outsides within the page.

Transit’s punctuation could be compared to Alice Notley’s 1992 The Descent of Alette, also set within a subway system navigated by a porous body confronting patriarchal space and employing quotation marks profusely. As Julia Bloch has described of the use of quotation marks in The Descent of Alette, these reference both orality and historiography: the sound and the cited.[1] Domingo’s Afterward conveys intentions behind her use of quotation marks, which are “often attributed (either truthfully or apocryphally) to a slightly more authoritative or solemn voice than that of the parenthesis” (127). As in the duality Bloch notes, authority in quotation references the quoted as having come before the poem, grappling with inheritance and placing herself in relation to that lineage. In employing quotation “either truthfully or apocryphally,” the poet puts herself among those speaking towards a public.

Parentheses likewise reference both a sound and that which preceded the poem, through patterning the visual forms of the cityscape: its bridges, domes, and vaulted arches, its circuits interrupted, its spatial sieves. While in one sense the parenthesis is a hushed tone, its interruption and isolation also shouts for attention. In the poem’s space of the Metro, a line approaching a curve sounds out friction, an interference, a squeal. Domingo describes parentheses as the voice “that whispers or rebuts (albeit in a measured tone) the affirmation of the quotation marks or of the un-punctuated voice.” This use of punctuation Domingo interprets as distinctly Mexican: “to affirm (though tentatively), to deny (but not fully), and, above all, to speculate” (127). The parenthesis in this telling suggests a change in volume (a smaller size, that which fits within what encloses it, and that which is not as loud), at once becoming a resource for sensorial documentation of the raucousness and multiplicity of the Mexico City streetscape.

Any writing about Transit follows the abundantly thoughtful criticism Greene himself has published about this book and its translation in myriad venues over numerous years. If Transit defies, as Greene has written, an “unwrinkled personal narrative, collective memory, or national history,” then perhaps it is the quotation marks and parentheses that can be read as the creases, the wrinkles. In Greene’s ‘Paratext,’ Transit’s wrinkles are described as “intertextual and porous — in a word, leaky, to borrow Kameelah Janan Rasheed's terminology” (137). Parentheses and quotation marks become a net that both holds and induces flow. Indeed, Greene elsewhere describes how, “a chorus of voices is allowed to interlace and interrupt one another” and the punctuation is a mechanism of this making-lace, this inter-rupturing. With reference to the poem ‘Tremblings’ on the 1985 earthquake, Greene has reflected on the poem’s “visible fractures.” Greene describes translating in a way that holds the text together just enough, to “put some ‘glue’ between Domingo’s shards without sanding down their sharp edges.”

The role of punctuation in the text would seem accessible only through description in metaphor. But the language of Transit interacts with the shape of quotation and parenthesis in space in a way is not ‘merely’ figurative, but a participation in patternmaking continuous with the cityscape. The curves of punctuation in the city is also geographical space: “parenthesis (vacant lot)” (31). The city’s lines bow under force and become curves as “columns / (go weak at the ankles)” (41) and “a rock traces an unheard-of parabola (its aim shatters one of modernity's windows)” (87). The city appears as a catalogue of signified shapes, eliding the difference with words as another such catalogue: “getting lost (to the panorama’s delight) rectangles (cones) semi- / ellipse (trapezoids) internal circumference and flattened circles (steady in their steel alignment) / convex and adjacent (perfect grid)” (33). In Transit, quotation marks and parentheses appear on virtually every line though not every word falls inside them, and there is a sense of haphazardness in this “cluttered jumble (trampled nature)” (25) of what falls within and outside points of division. These are partitions in space and in time, as the inherited and the new are tangled in a present, and the construction of this formal infrastructure is as precarious as the city. Which parts of the totality become the frame and which the selvedge cannot always be predicted.

“(in my fickle parentheses) nouns and creeping-vine pronouns bloom,” Domingo writes in the poem ‘Monument.’ A meta-poetic mode extends the continuity between page and cityscape from shapes to constructions of relationship. This poem is dedicated to the Mexican documentary poet Luis Felipe Fabre, one of many dedications in Transit to Mexican poets, as the poet seems to convene onto the page a lineage, communality and public for this work. The poet continues, “(in the face of my circumstantial adverbs’ apathy) a pick-up veers sharply toward the climax (its possessives screech) its bone-dry onomatopoeia smashes against dislocated direct object they “cackle” between adverb and indelible preposition” (89). This kind of meta-poetic writing might read as gratuitous on its own, “only” a metaphor, were it not for the work the poems, their translations and their book forms do to call into question modes of relationship between page and place. Greene’s translation amplifies, complicates and makes multiple Domingo’s study of what it means to represent a spatial practice on the page. A self-proclaimed “book farmer,” Greene engages not only the X and Y axis of the page, its breadth and height, but the Z axis, that always-present directionality which moves infinitely towards and away from the reader. In this way, Greene’s book-objects materially explore the relationship of a ‘translation’ to an ‘original’ by locating translation as a coordinate in space.

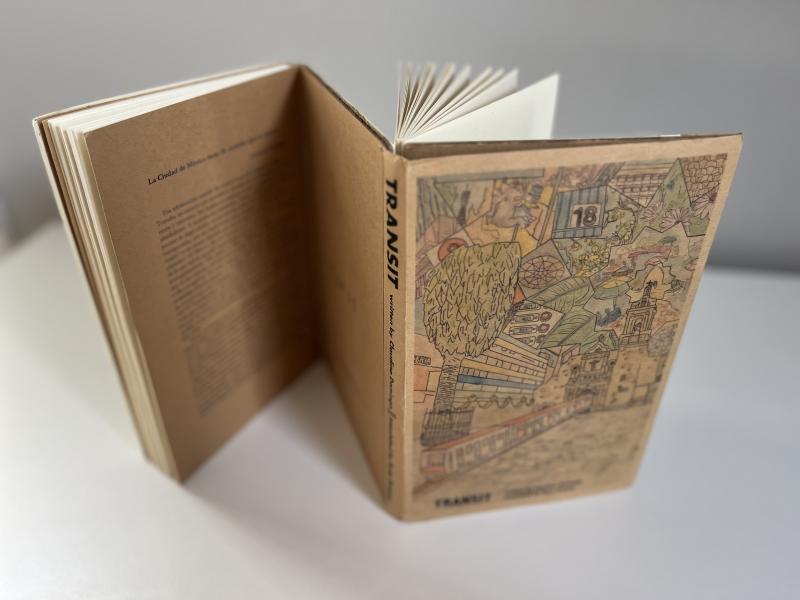

In the first book manifestation of Greene’s translation of Transit, that Z axis appeared as a literal Z manipulated in the hands of the reader. Greene published a selection of poems in a handmade dos-à-dos cardboard-backed edition. Rotating like a revolving door around a vertical axis, the book-object itself creates a circuit, a continuous opening and closing between ‘original’ and ‘translation.’ The two covers are differentiated by the bleached white paper of the original and recycled brown paper of the translation, folded over the recycled cardboard material of the cover, the book’s materials themselves invoking a circuitry of use.

In 2022, seven of the 24 poems appeared as Impossible Hours / Horas imposibles, published by the editorial death of workers whilst building skyscrapers in Manchester, England. In this manifestation, the original Spanish appears on a page opposite the English translation but on the verso side of a transparent page. The reader folds the original backwards against the translation, which suddenly creates clutter and clamor, until the reader slips in a cardstock sheet included in the book and printed with “smog backdrop for transparent reading.” The cardstock’s rectangular shape externalizes and obviates the shape of the page in accentuated contrast with the cover’s egg-like inked curves. Accompanying Impossible Hours / Horas imposibles was a sculpture-translation of the poem ‘Soledades’ / ‘Solitudes,’ a hanging mobile that creates a circularity of revolution around a vertical axis extended beyond consecutive pages. Light passing through the semi-translucent paper allows the poems themselves to reflect onto the spaces that prompted them.

After translating using Google Maps in street view to locate street corners and neighborhoods in Mexico City, Greene visited Domingo in 2017 to walk the routes of the poems. What resulted was what Greene terms an ‘audio map’ of recorded sounds at points and along routes referenced in the poems. Rather than merely a reflection of sites in Transit, Greene framed these as prospective prompts for further writing, where site becomes sound becomes text elsewhere, in another site. That visit also gave way to an ‘experiential translation’ of the poem ‘Sin destino fijo,’ which Greene published in Tripwire 16 in 2020. Greene here ‘translated’ Domingo’s spatial practice by following the poet’s sensibility and route on Metro Line 4 in Mexico City, while generating different words in the process, and the result is a ‘translation’ markedly distinct from the ‘original’ in form. Greene has also instigated audio experiments in the performance and conveyance of translation. One experiment took the poem as script, with parentheses and quotation marks indicating cues for different speakers, which Greene and Domingo recorded as a selection of poems in English and Spanish.

After the art book transfigurations through which the translation has passed, publication of all 24 poems in a more conventional paperback edition with a larger print run might have posed challenges to manifesting an argument about translation through the materiality of the book form. In the 2024 Eulalia Books publication, the interplay between original and translation manifests through the orientation of the original at a 90-degree angle to the translation, on the verso side of the pages. A square shape gives the book a wide weightiness, and turned to read the Spanish original the book has the feeling of a journalist’s legal pad. In the reader’s handling of the paperback, the poems accompany the author into the note-taking modality of the poet jotting on the subway. The translation seems to fall out of the bottom of the original, which “opened its trap doors,” (37) like a shaft, or a grate over a gutter. Rotating the paperback horizontal again, the pages curve and the reader traces an arc through space, a sort of invisible parenthesis opening and closing.

With this orientation, translation becomes less like standing face to face and more like turning a corner and bumping into something else. The spine of the book itself becomes a convex mirror in a subway corner conveying a breadth of scope only accessible at the corner. And this book is a compilation of corners: ““the world” with thorns and other prickpuncture things / (creeps up around every corner)” (23). It is there, as Domingo writes, “my / metaphors break down (as I turn the corner)” (13). Around the corner of translation in this edition, ‘this’ is not ‘that,’ but rather both this and that occupy a coordinate in space as the distance between them tugs and slackens, zooms in and out in a view necessarily distorted and expanded.

The word ‘parenthesis’ comes from the Greek: para ‘by the side of, beside, hence alongside of, by, past, beyond’ and thesis ‘putting, placing.’ Greene cites in the Paratext a “deep alongsideness” with many people who made possible the translation. That alongsideness becomes manifest not only in the text’s punctuated forms but in the materiality of its translations and their physical touching with an ‘original.’ Greene’s projects since beginning the translation of Transit have extended these questions by creating with community in Phoenix, Arizona, through F*%K IF I KNOW//BOOKS, no.good.home, and Cartonera Collective. “Ringing in my ears is always the voice of Mónica de la Torre,” Greene has written, “who argues that “voice necessarily ventriloquizes, necessarily voices.” In other words, all voice [and therefore all writing] is chorus ... is collage.” Greene’s practice of collage, of quotation, of parenthesis, goes beyond the page and towards a way of being with others. As Greene has said, “Sometimes the page doesn't feel like enough.”

The word ‘quote’ is from the Latin quota, ‘bearing what proportion of the total.’ That which is inside the quote is a ‘share’ of something beyond; the city on the page is necessarily a portion, and at once has the capacity to reference that never-representable totality that is urban space at large, and a sensation of the public. The many forms of Greene’s translations of Transit indicate his conviction that translation is itself a share. The book form is likewise a quote, a parenthesis, “alongside of, by” and not abstracted from or instead of the space it references. In the many lives of Greene’s translations of Transit, the totality towards which these translations and their objects continually point is that which is collective.

[1] Julia Bloch, “Alice Notley’s Descent: Modernist Genealogies and Gendered Literary Inheritance,” Journal of Modern Literature 35, no. 3 (2012): 1–24.

Architectures of Disappearance