Reading 'Los muros no son para siempre'/'Walls are not forever'

A collaboration of Maire Reyes, Nayeli Hernández, Iris Díaz, Ana Iram, Paloma Galavíz, Olga Guerra, Marcia Santos and Alejandra Aragón

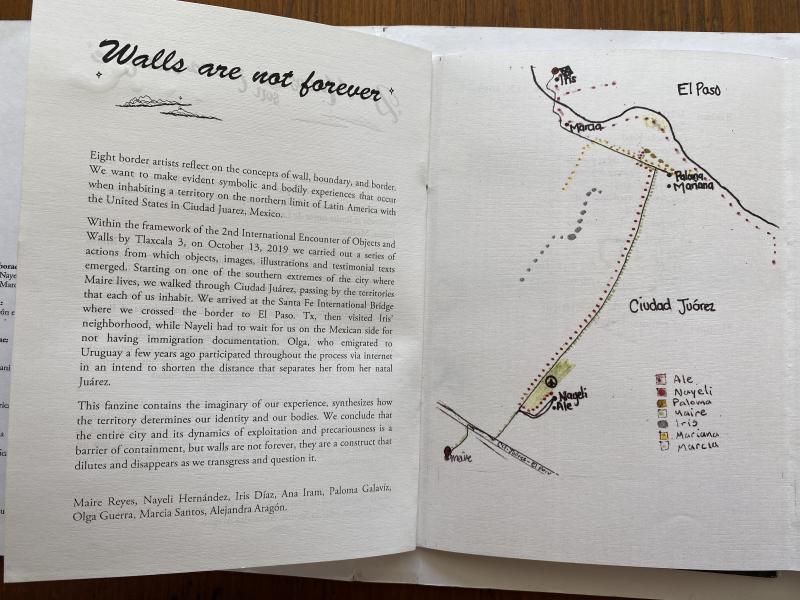

The zine opens to a map of dotted lines: barbs on a wire, punctured lines symbol of trails, punctuation of walking routes. The lines trace a walk taken on October 13, 2019, by border artists Maire Reyes, Nayeli Hernández, Iris Díaz, Ana Iram, Paloma Galavíz, Olga Guerra, Marcia Santos, and Alejandra Aragón. The walk traverses between the artists’ homes through Ciudad Juárez, on the border of El Paso, TX, concluding that “the entire city and its dynamics of exploitation and precariousness is a barrier of containment.” The project was created for the second International Encounter of Objects and Walls by Tlaxcala 3 (Mexico City) as a critical examination on the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and is accompanied by a film, Los muros no son para siempre (Walls are not forever). This is a project about how to perforate a line through route design, and how to document the body’s registration of constriction by walking.

Project introduction by Alejandra Aragón and Marcia Santos in collaboration with the artists, map of walking routes by Maire Reyes

Project introduction by Alejandra Aragón and Marcia Santos in collaboration with the artists, map of walking routes by Maire Reyes

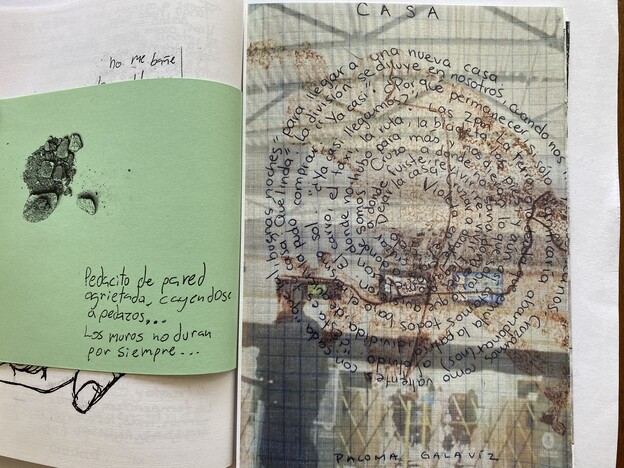

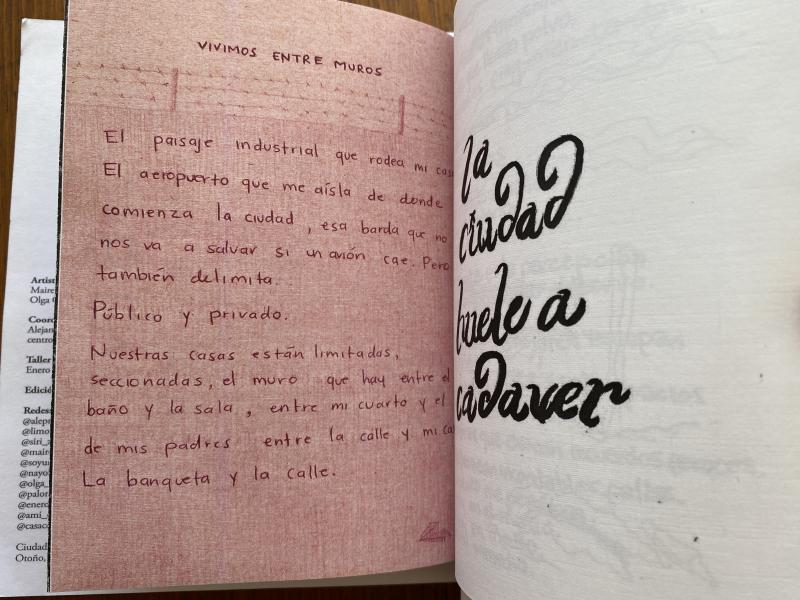

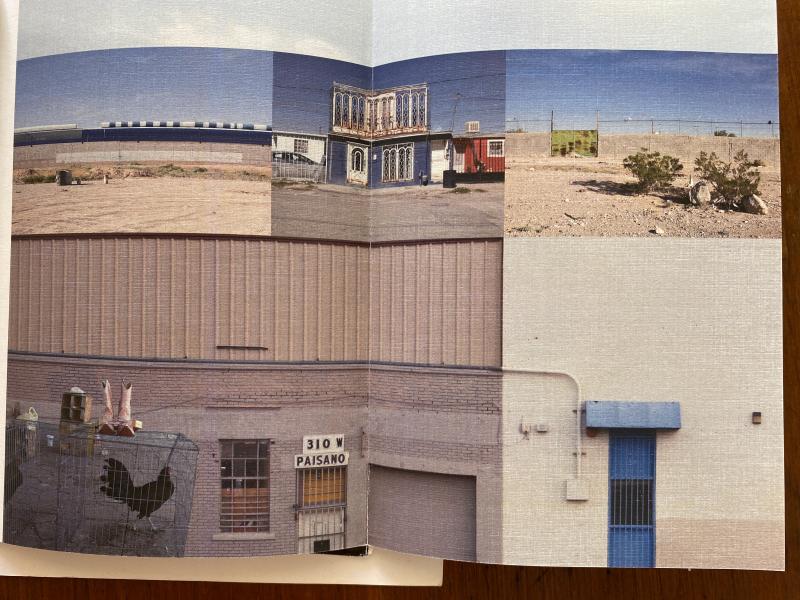

What does it mean to begin from home? The first carceral spaces on the pages are domestic, among intimate walls: the window grate, cinderblocked patio delimiting a space of play in a city described as “huele a cadáveres” (it smells/reeks of cadavers), the stressed syllable of “cállate” (be quiet/hush you/shush). The route begins at home at an extreme point of the city, in the enclave Jardines del Aeropuerto, the neighborhood of artists Maire Reyes and Alejandra Aragón. Proximate to the airport, the starting point is among the slash of im/mobility, verse read in the film by Nayeli Hernández: “We live between walls / the industrial landscape that surrounds my house / the airport that isolates me from where the city begins.” Amid imagery of apparently desolate, industrial desertscapes — distant mesa, pallet fencing, rolling tire, threadbare tarp coverings, acoustic wind, and thrum — the route is rather a peregrination between homes.

'Vivimos Entre Muros' by Nayeli Hernández, calligraphy on right by Marcia Santos

'Vivimos Entre Muros' by Nayeli Hernández, calligraphy on right by Marcia Santos

The spatial mapping of the carceral space of the current United States/Mexico border grounded in a visuality and authorial positionality of home bears kindred project with, among others, Omar Pimienta’s Album of Fences on the border in Tijuana, and Miguel Fernández de Castro’s Grammar of Gates on the Sonora/Arizona border and ancestral lands of the Tohono O’odham Nation. Los muros no son para siempre also articulates a direct affront to performances of walking in border space, both contemporary and historical, that become rather statements of right to a space not home, a means of amassing colonial cartographic data. JD Pluecker’s “Walk Me Onto Land” in Ford Over, for example, critically responds to such colonizing movement in following two walking figures through the works of Jean-Louis Berlandier and Lino Sánchez y Tapia, who travelled with the Mexican Border Commission in 1827–29. In this historical case, walking is concurrent with appropriating space of the border. Today, journalistic expeditions along the route of the border wall, or documentary travels such as the film The River and the Wall become more than anything performances of right of passage, the reification of the property line. In a spirit shared with Brett Story’s film The Prison in Twelve Landscapes, Los muros no son para siempre hardly shows blatant manifestations of state force: instead, the movements of the project itself articulate geographies of the excesses of the neoliberal state.

The zine is an apt form for a project attending to the scraps of experience of peripheries, the residues of sites on the body, the found objects, the lost dog, jotted sensations. The way in which seemingly peripheral, surplus spaces are integral to the structure of the border line is articulated in objects and notations moving through spaces of daily life. The movement towards the boundary wall at the speed of a walk creates a bisection of the wall’s organization of space. Carceral geographer Brett Story articulates an argument of Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag,

surplus land, surplus labor, surplus state capacity, and surplus capital geographically distributed along the poles of urban and rural space all threaten to produce crisis in a capitalist system, either economically, through over-accumulation, or socially, as political unrest … Prison infrastructure helps absorb over-accumulated capital and puts idled or surplus land back into productive use, partially and temporarily resolving some of the contradictions inherent to capital circulation.[1]

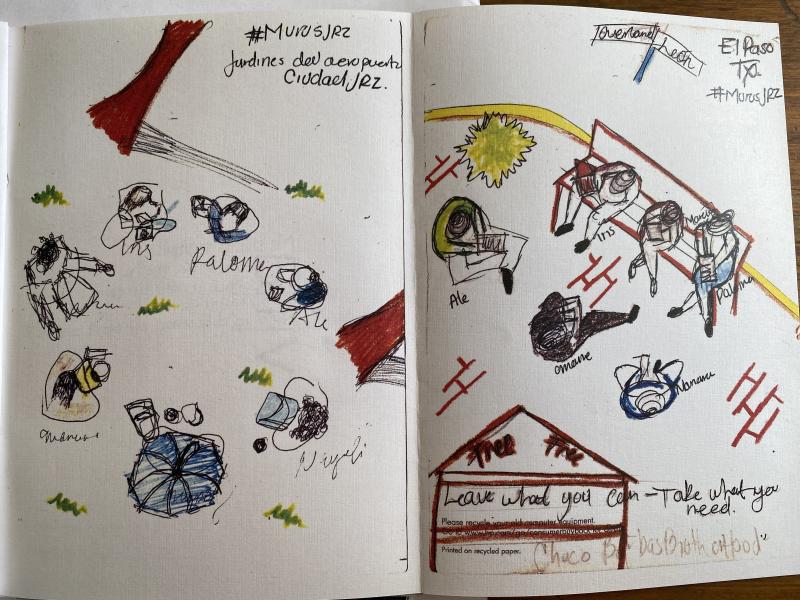

How can spaces of surplus and excess of the neoliberal, capitalist state be represented in route, verse, frame, sound? One response is the process of walking itself, using an approach involving embodied mapping to express a psychogeography. It’s an approach resonant with another defiant project of recording literary psychogeographies through walking routes in Ciudad Juárez, Juaritos Literario. The bodies of the artists confront distance and heat, note the sensation of walking with seven, circle together in urban spaces, scribble and jostle exhaustions. The walk is delimited by the span of the day: the daylight hours a verse of movement.

Drawings of artists sitting in an urban park in Juárez and in Duranguito, El Paso by Maire Reyes

Drawings of artists sitting in an urban park in Juárez and in Duranguito, El Paso by Maire Reyes

These spaces of surplus, excesses of the border wall, are also articulated by the artists as cracks and glitches, in a formulation extended by the work of Alejandra Aragón in La Grieta at the Edge of the World. The glitch brings us back to the origin point of the walk in a residence proximate to the airport and the potency of im/mobilities concentrated there. In an examination of airport noise, anthropologist Marina Peterson writes, “a sign of infrastructural failure or the materiality of digital technology, glitches are unintended sounds that are always potentially audible, with as much work required to keep them concealed as to make the intended sound heard.”[2] The pages fold out, the artists articulate a residence in the crack, in the unintended sounds of the border as glitch and in the excess spaces of the wall.

Photography by Alejandra Aragón

Photography by Alejandra Aragón

Maire Reyes, Nayeli Hernández, Iris Díaz, Ana Iram, Paloma Galavíz, Olga Guerra, Marcia Santos, and Alejandra Aragón, ‘Los muros no son para siempre’ (Walls are not forever) (Ciudad Juárez: Casa Centro X16, 2019)

@losmurosnosonparasiempre is a project of coordinator Alejandra Aragón, @aleprendelaluz edited with Amairani Dávila, with artist collaborators Maire Reyes, @maire_rey, @holymaigreen; Nayeli Hernández, @nayoladio; Iris Díaz; Ana Iram; Paloma Galavíz, @palomaglvz; Olga Guerra and Marcia Santos, @soyunabrujachula ; @limonada.electrica

1. Brett Story, Prison Land: Mapping Carceral Power Across Neoliberal America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 17–18.

2. Marina Peterson, Atmospheric Noise: The Indefinite Urbanism of Los Angeles (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 12.

Architectures of Disappearance