'Attention is the most important thing we can give to one another'

In conversation with JD Pluecker

This Commentary was written through collaboration with Mellon Humanities Collaborative fellows Rebekah Patnode and Tatiana Rodriguez about our conversation with JD Pluecker on October 26, 2021. This Commentary follows Reading JD Pluecker’s ‘Swamps Fly.’

Pluecker shows what lingers. In Swamps Fly, the carcerality of Houston’s existence (as Houston-the-unswamp, drained and deswamped by enslaved people of color) is communicated through description of what subsists from 1836, when the Republic of Texas was created to ensure slavery’s endurance, and Houston was settled. The birds, water, alligators, floodplain, insects linger — all archive of the swamp that the modern unswamp was. Pluecker uses time, historical archive, sound, and smells that linger in the space as reference points to draw attention to the settler colonial carceral history of Houston. In collaboration with artist Elana Mann, these elements are archived in another layer of time, closer to now, as monument to that lingering, declaration of the subsistence of the space’s continuous carcerality by evidencing that it reveals itself: a place where water moves, dirt is dark, leaves embed the floor of a drastically changed ecosystem that would revert anytime if it was released.

We approached our conversation with JD Pluecker amid a semester working to create sound walk routes relating to carceral geography in El Paso, Texas. We reached out, yearning for practical tools for experiencing places as archives that can be registered in language. More than a theory, we needed to know: what actually happens when you’re there? This tactical need shaped a fervent and generous conversation that allowed us to consider more amply the process of directing and documenting attention.

We are at a point in our project of writing walking scores for participants along a series of routes that, through their curation, make an argument about unexpected ubiquities of carceral space. We had become curious about how to write in a way that shaped attention while also staying conscious of the application of instructions to a place. Our first drafts of walking scores were rife with imperatives (turn left, go straight, look up), and something felt off. We were interested in how Pluecker had created this project that was about being in a place that had been absolutely shaped by imperatives imposed on the swamp: stay here, don’t budge, don’t bulge. Nevertheless, as readers of Swamps Fly, our attention felt stewarded without the force of imperatives.

As part of the project The Unsettlements, Pluecker made an intention to write sixty-four poems of sixty-four words each for their ancestors of seven generations ago. The chosen constriction would be to write these poems without pronouns or imperatives, constructions that they discussed as overwhelmingly overused in neoliberal institutions and also even in “social justice organizing”: you/we/them; join/do/help, etc. “Pronouns are replacing something else. Do you have to replace it?” Pluecker asked. Swamps Fly was written at a point of working with these constrictions, Pluecker described, “when I hadn’t let the structure collapse.”

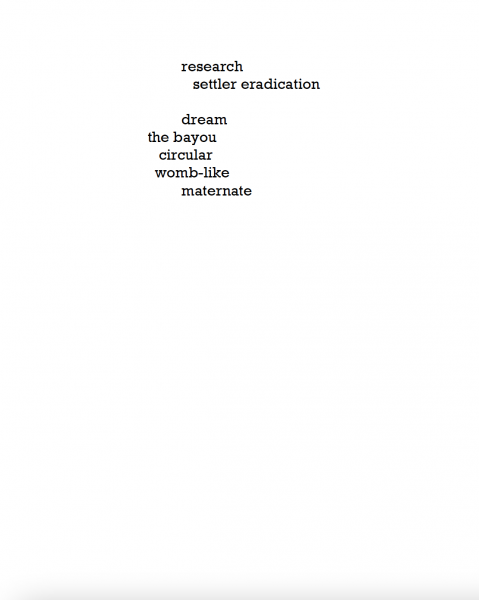

Lines in Swamps Fly deftly play with the edges of imperatives while never allowing for a singular definition — “research / settler eradication // dream / the bayou / circular / womb-like / maternate” (23). Pluecker read this section, and we heard how the word “dream” here is nearly an imperative, but it is also a noun. “Maternate” is brought to English from Spanish and nearly refers to “matérnate,” mother yourself. We understood this doubling and neithering as characteristic; “In general in poetry, I’m interested in the indeterminate.” Pluecker followed, “The way I know I wrote a poem is if I can go back to it later and find something I didn’t know about.”

from JD Pluecker’s Swamps Fly

from JD Pluecker’s Swamps Fly

One of the questions we are asking ourselves in relation to our project’s documentary element is: what is a monument? Pluecker referred to the many ways that language is a monument in their work. In an extension of these themes of the indeterminate and simultaneous, we appreciated the suggestion therein that the artist or creator is also a monument maker. This hopeful element illustrates the important fact that the monument can be erected as it is torn down; the act of tearing it down is also its creation.

Pluecker’s work explores the full story of that monument-phrase draining the swamp. The language is the monument; the swamp itself the archive, etched into “swamp parks.” As in El Paso, walking is unusual in Houston because of the forbidding heat. Yet for this project, the pace of the walk seemed to become a means of attesting to the pervasiveness of the swamp. Pluecker described that their perception of inhabiting landscapes had been reoriented by the idea that we can look at all spaces as gardens: “Every abandoned lot is also a garden. Every puddle that won’t drain is a swamp rising up to say ‘I’m still here.’”

The walk defies a speed enabled by encasing (“Remnants of the swamp that have to remain are imprisoned in this concrete”), by instead attesting to what lingers. In reference to a project of walking as collective archive, Pluecker shared with us Carrie Marie Schneider’s project Hear Our Houston.

Photo credit: JD Pluecker, featuring a sonic sculpture by Elana Mann.

As our group of fellows prepares to gather to lead each other in the sound walks we are developing in El Paso, we got to the question of what it means to Pluecker to experience a place as an archive. Pluecker described Swamps Fly as a project stretching between digital documentary archives and tactile archives through visits to swamp parks as urban/rural controlled spaces. Drawing on somatic rituals of CAConrad, site visits were occasions of letting words flow. That experience in presence would be followed by a process of online word scrambles from the language of notes and tactile scrambles in words printed out and cut up.

Part of our interest in creating the sound walks is to imagine the space as different in an embodied way. We are looking for what is disappeared. Archiving as monument building begins to help us think through ways to undo a fixed notion of the story or future of a space. We noticed and asked about the many negating prefixes in Swamps Fly: unforget, unsettlement, antimarker, unswamp, unwrought. So often, Pluecker described, the capitalist mode is “what’s going to get us out of this mess is to tell more stories.” This leads to a proliferation of stories rather than asking “how to un- these things,” how to untell the story. As Pluecker asks in “A Note to Aid the Undiscoverer” in Ford Over, “can words be re-used to un-mean, to un-discover, to earth?” Quoting M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, “Only in not-telling can the story be told.”

The crucial questions this project poses have to do with sufficient conditions for identity: “What is a swamp and what is not a swamp? If a swamp is drained, is it still a swamp or not a swamp?” JD Pluecker described Indigenous communities in what is now called Texas investigating similar questions of identity and time: “What is a person who was identified by the state as Mexican-American or Hispanic but is now reclaiming Karankawa identity?”

In Pluecker’s collaboration with artist Nuria Montiel in the 2016 project Karankawa Carancahua Carancagua Karankaway, they related to a Karankawa understanding of land as literally made out of the bodies of ancestors. This understanding was conveyed to the artists by elders of the Carrizo Comecrudo tribe, specifically Juan Mancias, who reminded them that the very earth one traverses in Texas is composed of the bodies of Native ancestors. As Pluecker asks, “What then is the sound of the land?” Swamps Fly seeks a syntax of an active landscape. With the landscape understood as active, Pluecker asked, “What kind of research does the swamp do?”

Reading Swamps Fly had us remember smelling smoke from a fire in Juárez from the vantage point of a house in central El Paso and thinking about the universality of that smoke, that it travels freely through air; that morning it was a solid concrete object — a building maybe, or a piece of furniture — and several hours later it was a smell that made it across a highly policed and politicized border that didn’t consider it contraband. The dust that frames everyone’s experience in El Paso, no matter who you are or where you live or how much you clean, and the landscape itself are sensory touchpoints in that way. Pluecker uses the same class of elements; through poetry, we are able to sense something that deepens our understanding of what they are conveying. This work is a reminder to look for these dynamic elements, to see and sense beyond the objectivity of traditional maps, for monuments and reference points that may not be what we traditionally think of as “points.”

What is disappeared lingers if we consider that the disappeared is subject and sensory. Pluecker’s juxtapositions of a swamp, alive before 1836 and today encased in concrete, actually illustrate that the space continuously reveals that which was disappeared. When we are able to feel the land’s past by what couldn’t be eradicated, those elements are archive. The same birds, the same bayous, the same plants, the same dark soil that shaped parts of the sensory experience of enslaved peoples’ forced labor and untimely deaths all remain. Through this conversation, we became drawn into attending to what has disappeared by recognizing unexpected touchpoints for attention.

Architectures of Disappearance