'Make absence more conspicuous'

In conversation with Celina Su

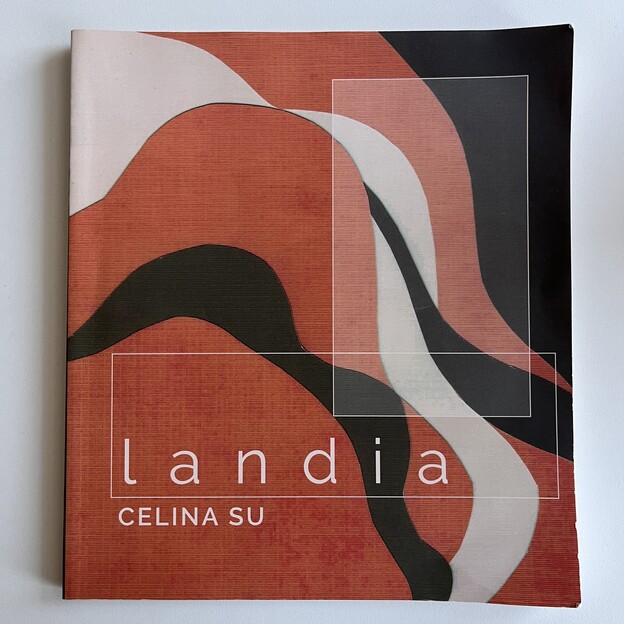

“If the forbidden cityscape is corporeal, then it is a proper burial, the entrails of the buildings devouring themselves with a vengeance” (Celina Su, “Seeing Like a State,” in Landia)

This commentary was written in collaboration with Tatiana Rodriguez and Adam Heywood, research fellows through the EPCC-UTEP Mellon Humanities Collaborative, when we gathered in conversation with Celina Su in February 2022.

We were drawn towards Celina Su’s Landia for what it could show us about paying attention and making present urban disappearances. As a poet and urban planner, Celina Su produces work that crosses epistemological fields in ways that provoked us. Celina Su saw our dialogue itself as a part of poetry’s methods for investigating place; acknowledging all documentation as fragmentary and incomplete, she opened our conversation by reflecting the intention of “making everything I write more of a conversation.” In that spirit, this commentary compiles collaborative questions that arose from our conversation, in the moment and months later.

How can the body document absences in a landscape?

How can poetry register the body’s documentations?

Su described a method of “triangulating hunches,” where the hunch is the gap, the suggested within the research process which hints towards subtext. Su takes triangulation as a means of documenting absence in the excavation of “different genealogies and layers,” a way of finding “how we got to where we are.” Su observed, “for investigations of gentrification, I always look for palimpsests: vestiges of what used to be.”

How to “make absence more conspicuous”?

Where, the hints of gaps?

In other words, what is peeking through?

As we created a set of Soundwalks in El Paso, we wondered about what peeks through both spatially and temporally. As a time-based form of art, a Soundwalk is a medium where a body can be present in a place, and at once sense and perceive overlaying peeks of the place’s palimpsest. Verse within Landia takes on formal representations of multiplicity and disappearance, the sentence itself an intentional measure of the splay of time. The poem “Seeing Like a State” describes, “I walk by as quietly as I can, to give him privacy in what yesterday was his living room. Where yesterday, at this hour, in this exact spot, one felt a cool shade” (22).

What can happen in the space of a gap?

What is the zoning of the page?

Where does the page invite a deviant loitering?

We noticed that Celina Su’s poems have gaps of different widths between words in certain lines. Su responded that her poems are visual versions of cacophonies in which the audience would pause before reading the next word. She then raised the question: how “can these words relate to one another in many ways?”

How to demonstrate polyvocality and the simultaneous presence of multiple histories?

How to create a page that bids non-linearity in the sense of a desire path?

In the section “Territories,” lines run across the bottom of the page like footnotes, marginalia.

Those continuities in space through which we move, which are formed for (our?) movement, but which run across the pages whether or not we turn them: a track, a shadow, a sidewalk, debris in the margin, Jena Osman’s drone, Susan Briante’s television ticker, a desire path of the eyes.

“When we see dilapidated infrastructures, we are reminded of time.”

We find the text at the bottom of the pages a little disjointed. We have to go back and reread some of the lines which the main text causes us to forget. We think this might be saying something about time, about remembering what is past and how what we are reading or interpreting in the present affects what we remember of the past.

“The ghostly Gowanus roofline I admired, now a Whole Foods store, / complete with rooftop garden, / atop a Superfund site. What remains / seeps into the soil, and our veins” (67).

The page seeps at different rates.

How can poetry be a site for thinking across scales?

On what scale do we respond?

“In 1964, my father set off for Brazil by cargo ship, taking three months to travel from L.A. to Panama to Curaçao to São Paulo. By the time he arrived, the military had seized the government in a coup” (29).

The ordering of these sentences, the listing of cities, gives the sense of movement through both time and space.

Poetry as an entry point to theorizing, lends itself “to a different set of likely research questions” as scales rub up against each other.

“What are the ways in which our renderings can try to dwell, to be in a moment, to have attention?”

Towards the end of the conversation, Su mentioned how we become desensitized to the environment around us, especially in an urban landscape. The everyday monotony of traversing from place to place becomes routine and we must find a way to look at our walks from a new perspective.

As Su put it, how do we “render what we know well as strange again”?

***

Su, Celina. Landia. Brooklyn: Belladonna Collaborative, 2018.

Our understanding of and appreciation for Celina Su’s work was deepened by reading Vi Khi Nao’s conversation in LitHub, Celina Su on Blending Academic Inquiry with Poetry, and “Fathom Deeply: Celina Su and Wah-Ming Chang in Conversation,” in the Poetry Foundation blog. The quotations above are Celina Su’s words in conversation and in Landia.

Architectures of Disappearance