‘Woodense’: A close twinning

A caged tiger who is regularly fed is probably not too keen to escape the quadrangle. Look at him — he’s mostly in the midst of a lazy yawn. A child who has never seen a tiger would find it hard to discover his ferocity behind the metal nets, and might instead be moved by his deep eyes, incisive canines and checkered fur. “Here is my new pet!” he might exclaim.

Aryanil Mukherjee’s “Woodense” is not a poem that takes such a juvenile jab at the tiger (one might be erroneously lured to think of Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Panther”). Rather, it is more about the “woods,” and about the “mouli,” or the “wives”; it is about the “bees,” the “honey,” and the “forest-department.” A whole network of closely connected themes. The “wood” seems to read as an extended metaphor at times, and at other times not. The specificity of transaction traditionally associated with metaphor is mostly missing from the “wood” and all its related concepts.

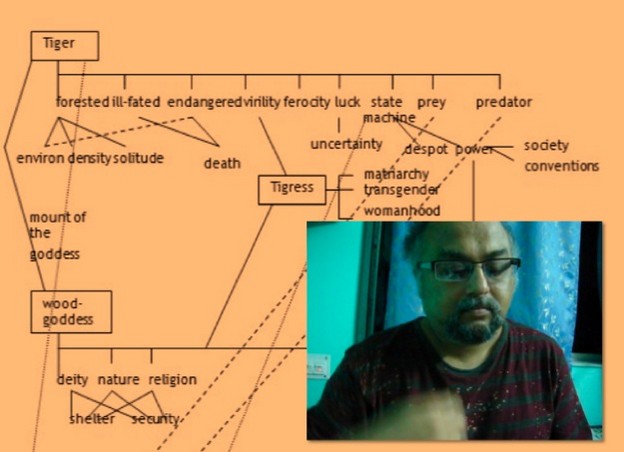

The poem is based on a newspaper feature (Appendix I) on the problems confronting a marginal community of honey collectors in the Sundarban area of West Bengal, India. During a discussion Mukherjee disclosed that he had graphed a thought-schema as a pre-text, much like a scenario, to use the language of films. The thought-schema, borrowing from graph theory, is an “object-oriented” diagram in the sense that the key themes mentioned in the report are objectified. Each “object” is represented by certain well-defined characteristics (usually descriptors), has a figuration in the theme hierarchy, and is interrelated with other objects.

The poem seems to intertwine two texts, a regular poetic text and a part-poetic-part-informative text, so as to guide the reader through the poem’s desired flow of logic. The thought-schema, in a nutshell, suggests structure that arranges the poem’s thoughts. It also tempts the reader to consider the objects in the poem as metaphors.

Parallel to the traditional metaphor there could be another kind that is indefinitely indiscrete, one that is not used to convey meanings or feelings. A whole commune of metaphors or “A-phors,” as we choose to call them, each with its clouded orbits uniting to initiate a collective thought-stream. The poem, as a result, dissipates ideas rather than controlling them. Because this A-phor-assembly is huskless and granular it seems to fit a wide range of thought-patterns.

The thought-schema of “Woodense” as sketched by the poet.

The thought-schema of “Woodense” as sketched by the poet.

It might be possible to compare the concept of Six-Sigma to the thought-schema of the poem. Six-Sigma is a technological philosophy, a vision; initiative- and goal-oriented, it can also be seen as a tool. In a nutshell, Six-Sigma can be used as a means to stretch out the thinking process. Essentially a business and technological production management strategy, the term “Six-Sigma” is borrowed from the statistical representation of certain phenomena in process capability study. It is defined by a 5-step process — Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify — expressed as a pentagon with the desired product (in our case, the poem “Woodense”) at the center.

Step I: What would be the first step of the process — “Define”? We feel it would probably be the newspaper feature from which the poem’s thought content originates.

Step II: In the “Measure” step, the poet selects certain facts from the report and/or other related sources, conceives and germinates ideas, develops an understanding of the relationship model that connects the “subjects” (expressed as “objects”) of the story.

Step III: For the poet, the “Analyze” phase is perhaps most important. The acquired data is digested in this step, which helped Mukherjee construct his thought-schema. This object-oriented relational model helped him discover a complex nexus of interrelations and dependencies that are not in the newspaper report and are apparently unseen. For example, he discovers the hidden connections between the tiger as state-machine and the worshipped wood-goddess Banbibi; how the poor, struggling mouli and his family become the proletariat, secretly opposed to the powerful (yet endangered) tiger and its protector, the forest department.

There is so much content in a wood! Trees, the strangely branched assemblies of their limbs, the bird collective, dread and curiosity. One imagination leads us to another — of human society and its demographics, its members as one monolithic block of life. Imagine their brain-wires as a single assembly — that makes a forest:

the hunter comes full circle and gets hunted

circles overlap as in a Venn diagram

Each singular feeling, every sensuous drive of every human adds up to mimic a forest’s density. Each individual is trying to live his own life according to a personal strategy. No one is ready to yield a bit. This leads to a social balance where every member is self-centered, making another kind of forest.

Step IV: The “Design” step is mostly about presentation; it involves the actual writing of the poem. In the case of a technological production procedure, the design and manufacturing phases are the most laborious, painstaking and practical. For a writer, this step might include the selection and structuring of language and the writing of the poem (the presentation). It is possible that for “Woodense” this step involved a forked activity where two texts were written separately and then plaited into one.

Step V: Art is usually not made to “Verify” anything, thus this last step might mean something very different for the writer. This could be seen as a reconsideration phase, where the writer either abandons his freshly composed work to gel or rot for a while and then re-examines it, or discusses it with fellow writers and friends before finalizing the work. This step marks the time when some of us would go back to Step I to revise the entire poem and the process that led to its creation.

Six-Sigma often uses a diagram popularly known as the Ishikawa/Fish-Bone diagram that highlights cause-effect relationships. It is often assumed that creativity is a spontaneous activity. The truth is that creative people use proven tools and techniques to forward their thinking. An augmentative schematic for the poem, different from Mukherjee’s thought-schema can be expressed in the form of a fish-bone diagram:

A fish-bone diagram represents the theme-data.

A fish-bone diagram represents the theme-data.

A fish-bone diagram helps in analyzing collected data. It should not be seen anything more than a tool for constructing thought structures and relating themes, ideas and concepts; by no means can it substitute or enhance poetic ability or imagination.

Now, in this wood, the tiger arrives. With its structure of social power, of political preference and economic disequilibrium, “a quarter on the left pan / a nickel on the right,” the poem seems to simulate the phenomenon of modern money mechanics via the complex tale of a rural society from the coastal forests of southern Bengal. Traditional narrative is avoided; instead, a mixed-media prose language derived from news, cut-up and embroidered with poetry, is interspersed among the poetic stanzas. In the end, it does become a poem of the self-devouring tiger — the common man of everywhere.

There is also an impending politics of religion. The common man begins to think — so much is still hazy, indistinct and obscure. That defines the birthplace of dread, of realization and submission. This is made clear through the figure of the mouli-wife, who submits to the ritual of augur and practices widowhood when the mouli enters the forest. She worships the forest deity and obfuscates truth by complying with superstition. However, positions of social power shift, quacks and clairvoyants assume immediate importance. Scales tip, reversing these binary gradients. The pure spiritual devotion of the mouli-wife is also present; she faces resistance from social consensus passed around as law:

forest department knows it all

observes measures

we accept the proprietor’s law as just

But she survives it. So does poetry, as it defeats and escapes the tiger’s prowl —

culture of workplace is above all

where bees swarm over the tiger

Appendix: Honey collection expedition begins in the Sundarbans

Anandabazar Patrika, April 15, 2010

Gosaba correspondent

The official honey collection season began in the Sunderbans last Monday. It’s likely that the intruders might encounter tiger attacks in the process of collecting honey from the deep forests. In the past, several collectors have lost their lives. The professional lives of the people of the Sunderbans have an intimate involvement with the tiger. Because most people live either as lumberjacks, honey-collectors or crab-hunters in the rivulets of the forest region, encounters with tigers are a regular affair for them, very often leading to the loss of human life. Since the Royal Bengal Tiger has been identified as an endangered species, guns or weapons are not allowed in these woods. The forest department occasionally uses shotguns with tranquilizer bullets. Faced with lives of extreme economic hardship, the local people choose to ignore the tiger. Tiger attacks are accepted as destiny. When the man goes into the forest, the wife knows that his return is uncertain. She has learned to accept it. When a family head has to venture into the woods, the wife practices a “mental widowhood.”

With the official start of the honey collection season last Monday, the mouli-wives have begun offering prayers to Banbibi, the wood-goddess. Temporary widowhood is being practiced in more than a thousand families. Until the husbands return, the wives and their families turn vegetarian. They refrain from using soap, oil, and vermillion; they take off their wedding bangles; and they stay barefoot and milk-clad, wearing white saris only.

Karunabala Sarkar, Laxmi Roy of Satjelia, Parul and Minoti Mandal of Lahiripur, Debaki Naskar, Sita Mistri of Sonagaon said, “This is an ancestral ritual for us. Until our husbands will return we will mourn their absence this way. Twice a day during this season we would offer water and honey to the sacred Banbibi and pray to her for the safekeeping of our men.” Tarubala Mondal, a sexagenarian from Jamespur, said, “We have had more tiger attacks this year. Quite often the tiger has entered the village. Now our folks have invaded its den. Mother Banbibi will protect them.”

The forest department has stated that the moulis are allowed up to two weeks for collection. All honey and wax collected will be purchased from the moulis by the State Department at government-stipulated rates. Anjan Guha, director of the Sunderbans Tiger Project and his team of observers are stationed on the river. Mr. Guha told us, “Some believe in superstitions, voodoos, some in the Banbibi, some in clairvoyants and jungle magicians. They all have their own ways to beat the dread. But most importantly we’ve given masks to the moulis. Masks that’ll scare away the tiger. They have been asked it use it at all times.”

Translated from Bengali by the authors.

Edited by Sarah Dowling