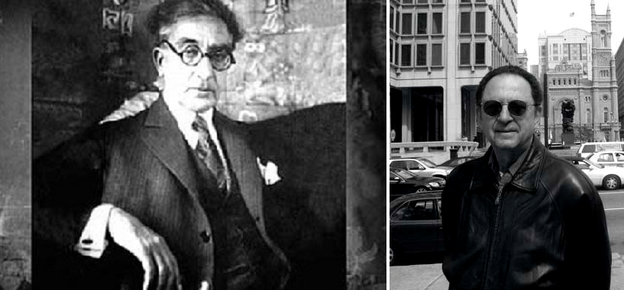

A tribute to George Economou, poet and translator

'From and About Cavafy'

[editor’s note. The following group of translations of poems by Cavafy and commentary thereon has been drawn from a lecture entitled “Adventures in Translation Land,” given at Tel Aviv University as the annual Nadav Vardi lecture on May 29, 2008, and on June 1, 2008, in the English Staff Seminar at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I was privileged to print it here several years ago and am reposting it now as a special tribute to master translator and poet George Economou, a major influence on my own life and times as a poet and assembler. Other work by Economou appears several times on Poems and Poetics. (J.R.)]

I first started reading Cavafy in the original in 1957 during my first visit to Greece, have continued to do so to the present day, and will surely do so for the rest of my days. The fact that I did not turn to translating his poems until some thirty years later never particularly mystified me, though once I started I did occasionally wonder why it took me so long. I believe I was too busy being quietly enriched and influenced by Cavafy in ways that have persisted in surprising me, ways that also accorded with my realization that the time had come to write my own Cavafy translations. Hence the title for this excerpt:

DROPPING ANCHOR AT ITHACA

Among the first of Cavafy’s poems I ventured to render into English is the title poem of my second small collection of poetry by him that is now in press, “Half an Hour.” Because this poem, written in 1917, was never published by the poet during his lifetime, presumably because of its homoerotic connotations, it has always been presented as one of his “Unpublished Poems,” and even ignored by the inexcusably ignorant. Ironically, there is nothing in the original Greek, and consequently in my translation of it, that assigns a specific gender to the individual addressed.

Half an Hour

Never made it with you and don’t expect

I will. Some talk, a slight move closer,

as in the bar yesterday, nothing more.

A pity, I won’t deny. But we artists

now and then by pushing our minds

can — but only for a moment — create

a pleasure that seems almost physical.

That’s why in the bar yesterday — with the help

of alcohol’s merciful power — I had

a half-hour that was completely erotic.

I think you knew it and

stayed on purpose a little longer.

That was really necessary. Because

with all my imagination and spell of the drinks,

I just had to see your lips,

had to have your body near.

A friend in Norman, Oklahoma, printed elegant postcards of this poem, which I thumbtacked alongside other literary and artistic curios on the front door of my office for the purpose of student edification when I was teaching at the University of Oklahoma. I lost count of the number of times I had to replace it there after it was ripped off, carefully I trust, by passing students whose eyes were hooked by the poem and who, I imagined, may have also perceived it as an aid to their own amatory ambitions. May their drafting of Cavafy as a kind of Cyrano de Bergerac into their campaigns to achieve true bliss have resulted in greater successes than the secret desires of either of these famous real and fictive poets ever did. Still, if ignorance is bliss, the pettily larcenous young lovers, whether winners or losers in their games of love, came out ahead.

The next two poems illustrate a theme that pervades much of Cavafy’s poetry, his unique perspective of the human condition through the trifocal lens of eros, memory, and art. Many of Cavafy’s poems deal specifically with the difficulties of the artist and poet, most notably the problem of the effects of time upon the artist’s ability to memorialize in his work a person or experience, invariably recalled for their erotic significance, for which he cares profoundly.

Craftsman of Wine Bowls

On this wine bowl of pure silver —

made for the house of Herakleides,

where grand style and good taste rule —

observe the elegant flowers, streams and thyme,

in whose midst I set a handsome young man,

naked, amorous, with one leg still

dangling in the water. — O memory, I prayed

for your best assistance in making

the young man's face I loved the way it was.

A great difficulty this proved because

about fifteen years have passed since the day

he fell, a soldier, in the defeat at Magnesia.

In this poem from 1921, in which the personal and the political, the private and the public subtly intersect, the artist, working on a commission by a great family, has the power nonetheless to insinuate his individual celebration of his love as he simultaneously experiences the eroding effects of time upon his memory of that love. That the craftsman persona dates his loss by the critical battle fought in 190 BCE that marks the onset of Roman dominance in the Hellenized East, provides an ironic historical context that may be more meaningful to the reader of this poem than to its speaker. Relative chronological proximity to the battle of Magnesia provides the speaker with poignancy, chronological distance provides the reader with ironic perspective. Perhaps the human dimensions of this context are large enough to accommodate the poet himself and us as well, revealing all of us as participants in our own private situations, full of passion and loss, and subject to historical forces that we are fated to understand only partially. Yet these pathetic, often tragic, conditions can be intermittently dignified by art’s attempt to record their sincerity and intensity.

A work that represents the consummate formulation of this rich and central aspect of Cavafy’s writing, “According to the Recipes of Ancient Greco-Syrian Magicians,” a late poem printed in 1931 two years before his death, is itself the answer to the question it states.

“What distillate of magic herbs

can I find,” said an aesthete,

“what distillate according to the recipes

of ancient Greco-Syrian magicians

that for a day (if its power

won’t last longer) or for just a moment

will bring back my age of twenty-three,

my friend of twenty-two,

bring back — his beauty and his love.

“What distillate can I find according to the recipes

of ancient Greco-Syrian magicians

that, in keeping with this retrospect,

will bring back our little room.”

With almost every Cavafian persona, including the autobiographical one, neatly subsumed in this undiluted common denominator of an “aesthete,” Cavafy makes the essential case for poetry, for searching out the knowledge of past masters, denoted by “Greco-Syrian magicians,” in order to describe as objectively as possible the quest to which he has dedicated his life in art. If the recipes to be followed can be construed as tradition and the precious distillate as the individual work of art — an interpretation I believe the discourse of the poem supports — how are we to apprehend its singular power, extracted by ancient prescriptions from “magic herbs,” if not by experiencing the poem in its totality, as a work of art, as defined by Paul Valéry, “constraining language to interest the ear directly”? Ever since I first read this poem aloud, it has occupied a place in my private anthology of poems great with sound. So it was reassuring to learn some years later that George Seferis considered it one of the most beautiful poems in the Greek language, an observation that redeems him in my eyes for having also remarked that Cavafy’s poetry is as prosaic as an “endless plain.” Surely as some things can’t be bought or taught (or completely carried over from one language into another), this poem’s greatness resides in the highest realization of its sense through its maker’s inimitable mastery of the sounds of his own special brand of Greek.

[Among George Economou’s twenty-first-century books are Acts of Love, Ancient Greek Poetry from Aphrodite’s Garden (New York: Random House/ Modern Library, 2006) and I’ve Gazed So Much, C. P. Cavafy Translations (London: Stop Press, 2001). Half an Hour, a second collection of Economou’s translations from Cavafy, was later issued by Stop Press, and his ultimate adventure in translation, Ananios of Kleitor, was published by Shearsman in 2009. During the 1960s he was the coeditor, with Robert Kelly, of the magazine Trobar and has been an active poet, translator, and scholar ever since.]

Poems and poetics