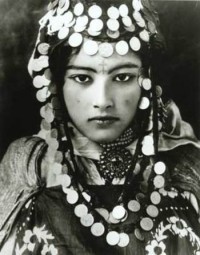

Outsider poems, a mini-anthology in progress (41): 'The Song of the Azria'

Adapted by Pierre Joris from Y. Georges Kerhuel's French version

Editorial note: The following is part of Pierre Joris’s ongoing exploration of North African (Maghreb) culture, a work as big & multifaceted as his own sense of the dynamics & far reach of poetic imagination & fancy. Yet the stakes here, as with much real poetry, go well beyond poesis as such, to exemplify & expose an area of religion & sexuality that has been a given in many parts of the world, “from origins to present.” Here the azria (courtesan) asserts the role of the outsider, still not forgotten, to raise new/old powers of body & mind in the service of vision & desire. (J.R.)

I am beautiful Azria

I am unfaithful Azria

I am the tender fruit

of a tree with tight clusters

I smile at everyone

I hate marriage

& for no price

will I admit slavery

I wear no veil

I hate all cloth

my happiness is

beauty and youth

my black eyes’

mysterious gaze

has the power

to enthrall my lovers

my Queen Kahina face

is more than bait

my mouth is made of honey

perfectly real

he who tastes it once

will return for more

my chest & its high breasts

draws in the holiest looks

while below my belt

lies nature’s sacred temple

where the faithful come to sin

in love my heart

often lies for

I am Azria

remorseless Azria

I accept the weak and the strong

I am carefree Azria

and my life is my life

my pride comes from my freedom

my life is crazy gaiety

from the most noble to the ugliest

my lovers are innumerable

I am Azria the dancer

who makes women jealous

I am the singer

I am the crooner

my gorgeous voice

opens all doors

Commentary

[Writes Joris selbst]: “This eponymous song, arranged by Y. Georges Kerhuel & included in the Encyclopédie de l’amour en islam Tome 1 (edit. Malek Chabel), speaks to the specific situation of Shawia Berber society in the Aurès mountains (northeastern Algeria). Mathéa Gaudry, a lawyer at the Appellate Court in Algiers, wrote about the Shawia courtesans in a treatise on Aurès culture in the 1920s: ‘The power of the Shawia woman does not pale with time. Knowledge of occult sciences, the prerogative of the elder, only reinforces it. […] The azria is a courtesan who received who she wants and goes where she wants. She sings, dances, plays cards, smokes and goes to cafés. No triviality in her manners; to the contrary: a tranquil self-assurance and often a natural distinction are her mark. Her courtiers’ enthusiasm surrounds her. They all show her a quasi-religious submission. When she intervenes, a fight will stop immediately.’”

Poems and poetics