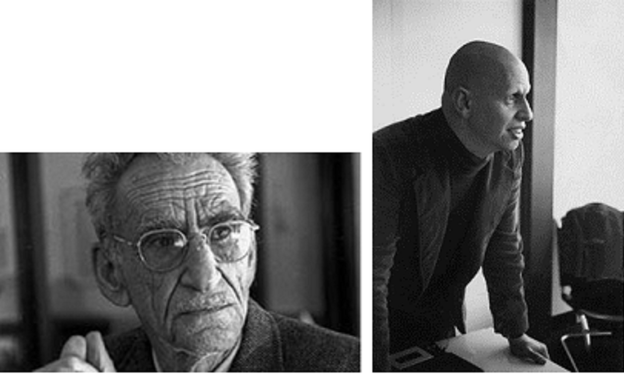

David Antin: 10 for George

[The following is a new work by David Antin, commissioned for The Oppens Remembered: Poetry, Politics, Friendship, edited by Rachel Blau Du Plessis & scheduled for publication in a new & important series from University of New Mexico Press. The over-all series, titled Recencies: Research and Recovery in Twentieth-Century American Poetics & under the directorship of Matthew Hofer, began last year with the publication of the collected letters of Amiri Baraka and Ed Dorn & promises more contemporary & modernist work in & out of series. David Antin’s selected talk poems, How Long Is the Present, edited by Steve Fredman, will also be published by New Mexico, scheduled for later this year.]

1.

A young man has written a slim book of poems. He has sent the manuscript to an older poet whose poetry he admires. The older poet approves of the work and allows his approval to be printed in the book as a kind of preface. His name is Ezra Pound. It’s 1934. The country is in a deep depression. Publishers are hit badly and are not promoting books by newcomers. The young man takes things into his own hands. He lives in Red Hook, which is the source of many of the book’s oblique images. It’s a working class neighborhood. But there is no work. He goes from door to door trying to sell his book. He’s a handsome young man. He sells a few.

2.

George has an intermittent correspondence with Pound, who advises him to go to France and gives him addresses of people to see. George and Mary visit a few of these writers and then decide to try to get a look at the country outside of Paris. They rent a horse and wagon and travel the backcountry for several weeks. Their agricultural vocabulary in French is greatly expanded.

3.

He’s in uniform now. He’s old for a soldier but the Germans have broken through our lines by the Ardennes. He’s technically a rifleman but the lines are confused and he thinks he’s with the motor pool now. But he’s crossing an open space all alone and suddenly the Germans are firing mortar shells at him. He sees a foxhole with two Americans. They’re waving at him to join them. He races across the field of fire and jumps into the foxhole. After nearly a minute of silence the mortars start up again. Then everything goes black. In the hospital he learns he’s wounded, the two G.I.s are dead and his war is over.

4.

The young man is now an older man. He lives in Mexico City now. He has a business there making furniture. He is good with his hands. He is on his way home from work. He will walk to the wide traffic circle where he will catch the bus home. The bus has just finished taking on passengers and is about to close its doors but there is a portly little man in a business suit with an attaché case rushing after the bus, waving and calling out to the driver to wait. He arrives at the bus just as the driver closes the door. He pounds on the door but the driver starts to go. The little man takes out a revolver and fires at the bus as the driver simply pulls away leaving the little man standing in the street waving and shouting. Slowly the bus traverses the circle and approaches the site of the original stop where the little man is still standing in the street and the bus would have hit him, but at the last minute he leaps back onto the sidewalk and fires at the bus again. Once again the bus traverses the circle and this time climbs up onto the sidewalk after the little man, who nimbly skips aside and fires again as he watches the bus drive away.

5.

In Mexico his business in high craft furniture is beginning to thrive. It’s a very small company with only one or two part time employees and he is the only artist designer. Sometimes he’s the only delivery boy. This day he has to get the chairs in a hurry to this high class mall. He loads the pickup carefully but is relatively uneasy. There is a strange lack of traffic. Something is going on. He comes back with a small package that he places under his seat. When he arrives at the mall there are large crowds of people carrying signs he can make nothing of. A big bearded man signals him to stop and leaps onto the running board. George slows down but shuts the window and keeps moving. The man addresses the crowd angrily and points to the truck. George stops the truck and reaches under his seat and pulls out his package, from which he extracts a Colt 45 revolver and places it with exaggerated care on top of the instrument panel, starts up the truck and watches the crowd sullenly give way.

6.

It’s in Redondo Beach. The war is over and George is sitting at a desk in a bank talking with a loan officer. The loan officer is a pale, middle aged man in a grey suit. He is looking through his wire rimmed glasses at a pile of papers on the desk before him. He straightens his tie and looks at George. George is wearing an old corduroy jacket and a blue work shirt. He has no tie. “You see,” the loan officer taps the pile of papers with his showy fountain pen,”You really don’t have much of a credit record.”

“You mean I don’t owe anybody any money.”

“You could put it that way.”

“Look I have a small lot just big enough for an 800 square foot bungalow. Doesn’t that count as collateral?”

“Undeveloped land is not liquid. You have only1300 dollars in the bank, no permanent employment, and you want to borrow 25000 dollars. “If I may say so, you’re not exactly a good risk.”

George suddenly shot to his feet and lunged across the desk, catching the guy by his necktie and dragging him across the desk, “Goddamn it, the U.S. government thought I was a good enough risk to keep its machines running while the Germans were shooting at us.”

It took two security guards to pull George off the guy.

7.

“David, you all treat me like a contemporary, but I’m old enough to be your father.”

”I don’t know. I never had a father.”

8.

After a reading of one of my early poems that featured a flood of similes, George remarked that he distrusted the word “like” for its too easy relation to an idea of truth. I responded that I’d never thought of the word “like” in relation to an idea of truth. I thought of it as an icepick to stab into an otherwise muddy reality. George shrugged his shoulders and said somewhat ruefully,” I suppose I’m still a man of the thirties.”

9.

While waiting for Elly and Mary to recover their coats from the crowded checkroom at the Guggenheim, George scanned the crowd and said to me, “You realize, David, ”we have the responsibility of being married to beautiful women.”

10.

I was on the way back home from a talk I’d given up at Sonoma and I thought I would drop in on George. We used to be neighbors back in Brooklyn, but we hadn’t seen much of him or Mary since they’d moved back to San Francisco. So I called and Mary said he’d definitely be there. I thought he looked pretty much the same, healthy handsome and tanned from spending the summer on the water up around Maine. He was in good form, telling a series of stories with a droll and understated wit. He got into a story about driving with Armand on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, which was as usual choked with cars, but moving briskly. Armand was in the fast lane going at a pretty good clip but keeping a reasonable distance behind a black Mercedes when a bright green Porsche with a Yale sticker on its rear window suddenly cut in front of us and the driver waved apologetically and turned on his left turn signal as Elly gave him the finger. George paused, rose in mid story and went to the refrigerator to take out a bottle from which he filled each of us a shot of bourbon and then went on. Armand gunned his engine and drew up alongside the Porsche, rolled down his window and yelled, “What are you? a historian?” I cracked up until I noticed that George while telling the story had very neatly poured our glasses back into the bottle and was replacing the bottle in the refrigerator.

Poems and poetics