Outside & subterranean poems, a mini-anthology in progress (59): Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, two dialect poems, with a note on Sor Juana & the pitfalls of translation

Translation from Spanish & related dialects or faux-dialects by Jerome Rothenberg & Cecilia Vicuña. Originally published in the blogger version of Poems and Poetics & later in The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry, edited by Edited by Cecilia Vicuña and Ernesto Livon Grosman, reprinted here for Jacket2. Final publication of the anthology of outside & subterranean poetry is scheduled for 2014 from Black Widow Press.

from VILLANCICO VII – ENSALADILLA

At the high & holy feast

for their patron saint Nolasco

where the flock of the redeemer

offers high & holy praises,

a black man in the cathedral,

whose demeanor all admired,

shook his calabash & chanted

in the joy of the fiesta:

PUERTO RICO – THE REFRAIN

tumba la-lá-la tumba la-léy-ley

where ah’s boricua no more’s ah the slave way

tumba la-léy-ley tumba la-lá-la

where ah’s boricua no more is a slave ah!

COPLAS

Sez today that in Melcedes

all them mercenary fadders

makes fiesta for they padre

face they’s got like a fiesta.

Do she say that she redeem me

such a thing be wonder to me

so ah’s working in dat work house

& them Padre doesn’t free me.

Other night ah play me conga

with no sleeping only thinking

how they don’t want no black people

only them like her be white folk.

Once ah takes off this bandana

den God sees how them be stupid

though we’s black folk we is human

though they say we be like hosses.

What’s me saying, lawdy lawdy,

them old devil wants to fool me

why’s ah whispering so softly

to that sweet redeemer lady.

Let this saint come and forgive me

when mah mouth be talking badly

if ah suffers in this body

then mah soul does rise up freely.

THE INTRODUCTION CONTINUES

Now an Indian assuaged them,

falling down and springing up,

bobbed his head in time and nodded

to the rhythm of the dance,

beat it out on a guitarra,

echos madly out of tune,

tocotín of a mestizo,

Mexican and Spanish mixed.

Tocotín

The Benedictan Padres

has Redeemer sure:

amo nic neltoca

quimatí no Dios.

Only God Pilzíntli

from up high come down

and our tlat-l-acol

pardoned one and all.

But these Teopíxqui

says in sermon talk

that this Saint Nolasco

mi-echtín hath bought.

I to Saint will offer

much devotion big

and from Sempual xúchil

a xúchil I will give.

Tehuátl be the only

one that says he stay

with them dogs los Moros

impan this holy day.

Mati dios if somewhere

I was to be like you

cen sontle I kill-um

beat-um black and blue

And no one be thinking

I make crazy talk,

ca ni like a baker

got so many thought.

Huel ni machicahuac

I am not talk smart

not teco qui mati

mine am hero heart.

One of my compañeros

he defy you sure

and with one big knockout

make you talk no more.

Also from the Governor

Topil come to ask

caipampa to make me

pay him money tax.

But I go and hit him

with a cuihuat-l

ipam i sonteco

don’t know if I kill.

And I want to buy now

Saint Redeemer pure

yuhqui from the altar

with his blessing sure.

A NOTE ON SOR JUANA & THE PITFALLS OF TRANSLATION

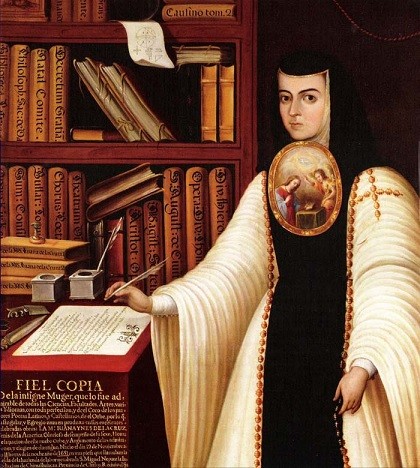

The centrality of Sor Juana to the poetry of the Americas is by now unquestioned, the great summation coming in Octavio Paz’s epical biography: “In her lifetime, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz [1651-1695] was read and admired not only in Mexico but in Spain and all the countries where Spanish and Portuguese were spoken. Then for nearly two hundred years her works were forgotten. After [1900] taste changed again and she began to be seen for what she really is: a universal poet. When I started writing, around 1930, her poetry was no longer a mere historical relic but had once again become a ‘living text.’”

In the translation, above, another side of her work emerges – one of less concern to Paz than to the present translators: her experiments with a constructed Afro-Hispanic dialect & with the incorporation of native (Nahuatl) elements into her poetry. Here the translation question comes up as well, not only the issue of political aptness, which may also be raised where the class & status of the poet & her subject are at odds, but something at the heart of the translation process as such. For it is with dialect that translation – always a challenge to poetic composition – becomes or seems to become most elusive. Though many dialects approach the autonomous status of languages, there is always the presence behind them of the official, dominant language, which can make them, in the hands of a poet like Sor Juana (as with a Belli or a Burns in a European context), an instrument for the subversion both of language & of mores. Their particularity is nearly impossible for the translator to emulate, even while bringing up similar particularities in the dialects or faux-dialects into which he translates them.

The wordings in the villanicos (carols) presented here are faux-dialects with a vengeance, while their intention (or hers, to be more precise) seems obviously liberatory in practice. We have chosen therefore to approximate both the measure in which the poems were written & the spirit of invention & play through which the dialects were constructed. For this our principal models for transcription & composition come from nineteenth-century American & African-American dialect poetry & practice, much of it as artifactual & inauthentic as our approximations here. Our view, like that of Sor Juana four centuries before, is from the outside, looking in.

Poems and poetics