The Tjurunga

Poem and note by Clayton Eshleman

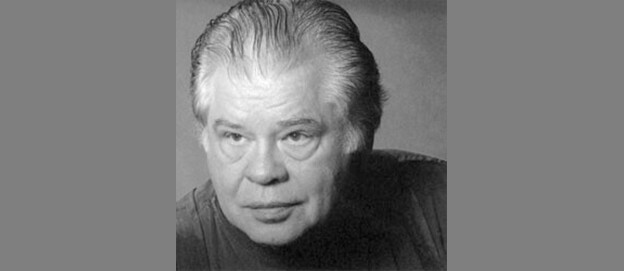

[There was with Clayton Eshleman a ferocious wisdom that came through in his remarkable poetry and in a range of translations (Vallejo, Césaire, Artaud, and others) that entered into his own dreamlife and wakenings in a way unknown to most poet-translators: a narrative of interactions with his subject that is without precedent and with a deliberate consciousness of what he’s doing and why and of how he may fail in that effort. The following poem, then, in the shadow of his recent death, is a piece from a few years back that I had prepared with him for Poems and Poetics but had never posted. His importance for my own life and workings is impossible, at this moment, to fully express, and his absence now is an irremediable loss. (j.r.)]

THE TJURUNGA

begins as a digging stick, first thing the Aranda child picks up.

When he cries, he is said to be crying for

the tjurunga he lost

when he migrated into his mother.

Male elders later replace the mother with sub-incision.

The shaft of his penis slit, the boy incorporates his mother.

I had to create a totemic cluster in which imagination

could replace Indianapolis, to incorporate ancestor beings

who could give me the agility

— across the tjurunga spider’s web —

to pick my way to her perilous center.

(So transformationally did she quiver,

adorned with hearts and hands,

cruciform, monumental, Coatlicue

understrapping fusion)

Theseus, a tiny male spider, enters a tri-level construction:

look down through the poem, you can see the labyrinth.

Look down through the labyrinth, you can see the web:

Coatlicue

sub-incision Bud Powell

César Vallejo

the bird-headed man

Like a mobile, this tjurunga shifts in the breeze,

beaming at the tossing

foreskin dinghies in which poets travel.

These nouns are also nodes in a constellation called

Clayton’s Tjurunga. The struts are threads

in a web. There is a life blood flowing through

these threads. Coatlicue flows into Bud Powell,

César Vallejo into sub-incision. The bird-headed man

floats right below

the pregnant spider

centered in the Tjurunga.

Psyche may have occurred, struck off

— as in flint-knapping —

an undifferentiated mental core.

My only weapon is a digging stick

the Aranda call papa. To think of father as a digging stick

strikes me as a good translation.

The bird-headed man

is slanted under a disemboweled bison.

His erection tells me he’s in flight. He drops

his bird-headed stick as he penetrates

bison paradise.

The red sandstone hand lamp

abandoned below this proto-shaman

is engraved with vulvate chevrons — did it once flame

from a primal sub-incision?

This is the oldest aspect of this tjurunga, its grip.

*

When I was six, my mother placed my hands on the keys.

At sixteen, I watched Bud Powell sweep my keys

into a small pile, then ignite them with “Tea for Two.”

The dumb little armature of that tune

engulfed in improvisational glory

roared through my Presbyterian stasis.

“Cherokee”

“Un Poco Loco”

sank a depth charge into

my soul-to-be.

This is a tjurunga positioning system.

We are now at the intersection of Coatlicue

and César Vallejo.

Squatting over the Kyoto benjo, 1963,

wanting to write, having to shit.

I discovered that I was in the position of Tlazoltéotl-Ixcuina.

But out of her crotch, a baby corn god pawed.

Recalculating.

Cave of

Tlazoltéotl-Ixcuina.

The shame of coming into being.

As if, while self-birthing,

I must eat filth.

I was crunched into a cul-de-sac I could destroy

only by destroying the self

that would not allow the poem to emerge.

Wearing my venom helmet, I dropped, as a ronin, to the pebbles,

and faced the porch of Vallejo’s feudal estate.

The Spectre of Vallejo appeared, snake-headed, in a black robe.

With his fan he drew a target on my gut.

Who was it who sliced into the layers of wrath-

enwebbed memory in which the poem was trussed?

Exactly who unchained Yorunomado

from the Christian altar in Clayton’s solar plexus?

The transformation of an ego strong enough to die

by an ego strong enough to live.

The undifferentiated is the great Yes

in which all eats all

and my spider wears a serpent skirt.

That altar. How old is it?

Might it cathect with the urn in which

the pregnant unwed girl Coatlicue was cut up and stuffed?

Out of that urn twin rattlesnakes ascend and freeze.

Their facing heads become the mask of masks.

Coatlicue: Aztec caduceus.

The phallic mother in the soul’s crescendo.

But my wandering foreskin, will it ever reach shore?

Foreskin wandered out of Indianapolis. Saw a keyboard, cooked it in B Minor.

Bud walked out of a dream. Bud and Foreskin found a waterhole, swam.

Took out their teeth, made camp. Then left that place, came to Tenochtitlan.

After defecating, they made themselves headgear out of some hearts and lopped-off

hands.

They noticed that their penises were dragging on the ground, performed sub-

incision, lost lots of blood.

Bud cut Foreskin who then cut Bud.

They came to a river, across from which Kyoto sparkled in the night sky.

They wanted to cross, so constructed a vine bridge.

While they were crossing, the bridge became a thread in a vast web.

At its distant center, an immense red gonad, the Matriarch crouched, sending out

saffron rays.

“I’ll play Theseus,” Bud said, “this will turn the Matriarch into a Minotaur.”

“And I’ll play Vallejo,” Foreskin responded, “he’s good at bleeding himself and

turning into a dingo.

Together let’s back on, farting flames.”

The wily Minotaur, seeing a sputtering enigma approaching, pulled a lever, shifting

the tracks.

Foreskin and Bud found themselves in a roundhouse between conception and absence.

They noticed that their headgear was hanging on a Guardian Ghost boulder engraved

with breasts snake-knotted across a pubis.

“A formidable barricade,” said Bud. “To reach paradise, we must learn how to dance

this design.”

The pubis part disappeared. Fingering his sub-incision, Bud played “Dance of the

Infidels.”

Foreskin joined in, twirling his penis making bullroarer sounds.

The Guardian Ghost boulder roared: “WHO ARE YOU TWO THE SURROGATES

OF?”

Bud looked at Foreskin. Foreskin looked at Bud.

“Another fine mess you’ve gotten us into,” they said in unison.

Then they heard the Guardian Ghost laughing. “Life is a joyous thing,” she chuckled,

“with maggots at the center.”

THE TJURUNGA (A NOTE) BY C.E.

I was first alerted to the tjurunga (or churinga, as it is also spelled) by Robert Duncan in his essay “Rites of Participation” (from The H.D. Book), which appeared in Caterpillar #1, 1967. Duncan quoted Geza Róheim (“The tjurunga which symbolizes both the male and female genital organ, the primal scene and combined parent concept, the father and the mother, separation and reunion … represents both the path and the goal”) and then commented: “This tjurunga we begin to see not as the secret identity of the Aranda initiate but as our own Freudian identity, the conglomerate consciousness of the mind we share with Róheim … the simple tjurunga now appears to be no longer simple but the complex mobile that S. Giedion in Mechanization Takes Command saw as most embodying our contemporary experience: ‘the whole construction is aerial and hovering as the nest of an insect’ — a suspended system, so contrived that ‘a draft of air or push of a hand will change the state of equilibrium and the interrelations of suspended elements … forming unpredictable, ever-changing constellations and so imparting to them the aspect of space-time.’”

Reading Barry Hill’s Broken Song / T.G.H. Strehlow and Aboriginal Possession (Knopf, 2002), brought back and refocused Duncan’s words.

In vol. 13 of The Collected Works, para. 128, Jung writes: “Churingas may be boulders, or oblong stones artificially shaped and decorated, or oblong, flattened pieces of wood ornamented in the same way. They are used as cult instruments. The Australians and the Melanesians maintain that churingas come from the totem ancestor, that they are relics of his body or of his activity, and are full of arunquiltha or mana. They are united with the ancestor’s soul and with the spirits of all those who afterwards possess them … In order to ‘charge’ them, they are buried among the graves so that they can soak up the mana of the dead.”

Poems and poetics