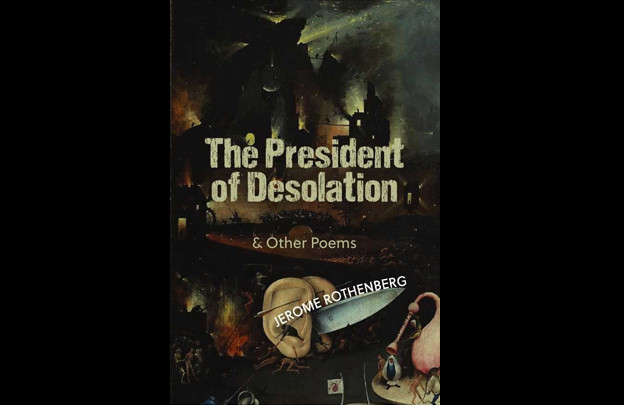

Postface to 'The President of Desolation'

Now available from Black Widow Press

[In announcing the publication of my latest book of poems from Black Widow Press, I thought the following postface might be of interest in what I say about the book’s title and the concerns that inform the book as a whole. Further information, for those who seek it, can be found at the Black Widow website, but for now I would hope to make the context of the work, including a number of procedural and aleatory poems, as clear as possible. The span of time covered is from the end of the previous century through the first two decades of this one. (J.R.)]

POSTFACE

The title of the present gathering — like much of what I’ve written over the years — points to the time through which we’re now living and to the times before through which I’ve also lived. The sense of desolation and devastation — a sadly rhyming pair — continues to inform our lives as vulnerable beings, both politically and ecologically, and it enters into our words and thoughts as poets in what Pablo Neruda famously titled our (all too bounded) “residence on earth.” To all of this I am a witness, or, better put, the poems bear witness on my behalf, even where the writing is procedural or seeming to put process over substance — and maybe especially then. In composing this book I’ve inserted some accounts concerning form and occasion, but my sense of the life and politics outside the book come across more directly in the following excerpt from an interview recently conducted for Spanish publication by the Mexican poet Javier Taboada.

Javier Taboada: I would like to link one of your poems, “Twentieth Century Unlimited,” with the outcome of the presidential elections (2016) in the United States:

As the twentieth century fades out

the nineteenth begins

again

it is as if nothing happened

though those who lived it thought

that everything was happening

enough to name a world for & a time

to hold it in your hand

unlimited the last delusion

like the perfect mask of death

Do you think that the “last delusion“ has already been unmasked?

Jerome Rothenberg: The poem goes back to the 1990s when the Cold War was coming to an end and with it — for better or worse — many of the twentieth-century dreams of human perfectibility and unlimited progress that we had taken too easily for granted. That was the “last delusion” I was talking about then, but the still darker thrust of the poem was the sense, already forming, of a retrogression to precisely the conditions that those dreams and delusions were aiming to address. We were moving, in other words, into a new century and millennium, but what was emerging already was a return to the conditions of the century before: “nationalism, colonialism and imperialism, ethnic and religious violence, growing extremes of wealth and poverty” in the description Jeffrey Robinson and I provided for the preface to the third volume of Poems for the Millennium. To which we added: “All reemerge today with a virulence that calls up their earlier nineteenth-century versions and all the physical and mental struggles against them, struggles in which poetry and poets took a sometimes central part.”

This wasn’t prophecy (though it might have been) but my sense of history speaking and unfolding for us in the here and now. And it has only intensified over the last two decades: the farce that history has now become in Trump’s time, but not without the threat of tragedy as well. To speak more specifically, what’s marking the present century — whether it resembles the nineteenth or not — are two distinct emergences: the rise of ISIS-like religious movements over the last two decades (and not only Muslim) and the rise of the nationalism and jingoism that Trump is bringing to us in the United States, and others like him elsewhere. Not to equate the two too easily, both are threats to a fact-based sense of reality on the one hand and to an open life of the imagination on the other, and my own push, like that of most poets I know, is to bring the two together: “imaginary gardens with real toads in them,” as Marianne Moore once had it.

So yes, I think the mask has already fallen off and we again have to take account of the actual present that confronts and threatens us. For this, poetry would be my own immediate answer, as it has always been, but there are other answers as well — and maybe, in the short run, better. Under any circumstances, the threats of violence and closure are what we have to stand against — wherever found and however answered.

Those anyway are the deeper thoughts (“too deep for tears”) underlying the bulk of my present writings, and I thought it useful to call attention to them here.

Taboada: Is this what you meant when in “A Further Witness” you wrote: “the age of the assassins/ once deferred/ comes back/ full blast”? Where do you think all this will lead?

Rothenberg: At my age I’m suddenly feeling closed off from a future that I’m not likely to see, but I can try to answer the question as if I’ll be a part of it. With that in mind I can reconstruct fairly easily what I was getting at in A Further Witness: the sense of terrorism (also a tactic with nineteenth-century roots) as a notable and distressing fact of our new and present reality. By assassination, then, I mean murder as a public and political act, not only aimed at rulers and leaders but, very much so, at the world-at-large. I could have also said the age of the murderers but I think that “age of the assassins” carries an echo for me and others of something from Rimbaud (Voici le temps des Assassins); at least that was the way I used it here. And there was also the other word that kept coming into the poetry — cruelty — as a signal of what we had to fear in the world that we knew from before and that kept coming back no matter how much we tried to defer it. As much as I feared and hated it, whether active or passive, I knew it was something that had to be right there, at the core of what I thought and wrote as a poet. It is for this reason that I used it several times as a book title, A Cruel Nirvana, in English, French, and Spanish, and in a poem of that name, which ends with these lines:

It is summer

but the trees

are dead.

They vanish with

our fallen friends.

The eye in torment

brings them down

each mind a little world

a cruel nirvana.

That would put it even at the heart of religious or spiritual attempts to escape it — the cruelty of the escape from cruelty — but its most hideous effects are in the public world and in the murders and tortures that serve as instruments of policy or, worse yet, of belief. So the idea, much needed today, is not to exclude it but to bring it into the body of the poem, as a sign of both the terror and the pity that the poem calls forth.

Poems and poetics