Alejandra Pizarnik: Four tales, translated with commentary by Cole Heinowitz

AGAINST

I try to recall rain or crying. The obstacle of things that don’t want to go down the path of innocent desperation. Tonight I want to be made of water, want you to be made of water, want things to slip away like smoke, imitating it, showing the final signs — gray, cold. Words in my throat. Stamps that can’t be swallowed. Words aren’t drinks for the wind, it’s a lie what they say, that words are dust — I wish they were — then I wouldn’t now be saying the prayers of an incipient madwoman dreaming of sudden disappearances, migrations, invisibilities. The taste of words, that taste of old semen, of an old womb, of lost bone, of an animal wet with black water (love forces me to make the most hideous faces before the mirror). I don’t suffer, I’m only expressing my disgust for the language of tenderness, those purple threads, that watered-down blood. Things hide nothing, things are things, and if someone comes up to me now and tells me to call a spade a spade I’ll start to howl and beat my head against every deaf, miserable wall in the world. The tangible world, prostituted machines, an exploited world. And the dogs insulting me with their proffered fur, slowly licking and leaving their saliva in the trees that drive me mad.

[1961]

DESCRIPTION

Falling until you touch the absolute bottom, desolate, made of an ancient silencing and figures that keep saying something referring to me, I can’t understand what, I never understand, no one could.

These figures — drawn by me on a wall — instead of displaying the motionless beauty that was once their prerogative now sing and dance since they’ve decided to change their nature (if nature exists, if change, if decision … ).

This is why my nights are filled with voices coming from my bones, and also — and this is what makes it hurt — visions of words that are written yet still move, fight, dance, spurt blood, and then I see them hobbling around with crutches, in rags, cut from the miracles of a through z, alphabet of misery, alphabet of cruelty. The one who should have sung arcs through silence while it whispers in her fingers, murmurs in her heart, in her skin a ceaseless moan …

(You have to know this place of metamorphosis to understand why it hurts in such a complicated way.)

[1965]

DISTRUST

Mama told us of a white forest in Russia: “… and we made little men out of snow and put hats we stole from great-grandfather on their heads … ”

I eyed her with distrust. What was snow? Why did they make little men? And above all, what’s a great-grandfather?

[1964]

A MYSTICAL BETRAYAL

Behold the idiot who received letters from the outside.

— Paul Éluard

I’m talking about a betrayal. I’m talking about a mystical deception, about passion and unreality and the reality of mortuaries, about bodies in shrouds and wedding portraits.

Nothing proves they didn’t stick needles in my image. It’s almost strange I didn’t send them my photo along with needles and an instruction manual. How did this story begin? That’s what I want to investigate, but in my own voice and with no poetic design. Not poetry but policy.

Like a mother that doesn’t want to let go of the child that’s already been born — that’s how its silent takeover is. I throw myself into its silence, drunk with magic premonitions of uniting with silence.

I remember. A night of screams. I rose up and there was no possibility of going back; I rose higher and higher, not knowing if I’d arrive at a point of fusion or stay with my head nailed to a post for the rest of my life. It was like drinking waves of silence, my lips moved like they were underwater, I was drowning, it was as if I were drinking silence. Inside me were myself and silence. That night I threw myself from the highest tower. And when we were at the top of the wave, I knew that this was mine, and even what I’ve looked for in poems, in paintings, in music, a being that was brought to the top of the wave. I don’t know how I gave myself over, but it was like a great poem: it couldn’t not be written. And why didn’t I stay there and why didn’t I die? It was a dream of the highest death, the dream of dying while making the poem in a ceremonial space where words like love, poetry, and freedom were actions in living flesh.

This is what her silence intends.

It creates a silence in which I recognize my resting place when the litmus test of her affection must have been to keep me far from silence, to bar my access to this region of exterminating silence.

I understand, understanding is useless, no one has ever been helped by understanding, and I know that now I have to go back to the root of that silent fascination, this gulf that opens for me to enter, me the holocaust, me the sacrificial lamb. Her person is less than a ghost, than a name, than emptiness. Someone drinks me from the other side, someone sucks me dry and discards me. I’m dying because someone created a silence for me.

It was a masterful job, a rhetorical infiltration, a slow invasion (the tribe of pure words, hordes of winged discourse). I’m going to try to extricate myself, but not in silence, for silence is a dangerous place. I must write a lot, capture expressions so that little by little her silence will grow quieter and then her person will fade away, that person I don’t want to love, it has nothing to do with love but rather with unimaginable and therefore unspeakable fascination (getting closer to the harsh, to the soft fog of her distant person, but the knife sinks in, it tears, and a circular space made from the silence of your poem, the poem you’ll write afterwards, in place of the slaughter). It’s nothing more than a silence, but this need for real enemies and mental lovers — how did she know that from my letters? A masterful job.

Now my nervous she-wolf footsteps around the circle of light where they slip the correspondence. Her letters create a second silence even denser than that of her eyes from the window of her house facing the port. The second silence of her letters gives rise to a third silence made of the absence of letters. There’s also the silence that oscillates between the second and third: encrypted letters in which she speaks in order not to speak. The entire range of silences while from the other side they drink the blood I feel myself lose on this one.

Nevertheless, if this vampiric correspondence didn’t exist, I’d die from the lack of such a correspondence. Someone loved me in another life, in no life, in all lives. Someone to love from my place of reminiscence, to offer myself up for, to sacrifice myself to as if with that I could provide a fair return or restore the cosmic order.

Her silence is a womb, it is death. One night I dreamt of a letter covered in blood and feces; it was in a wasteland and the letter moaned like a cat. No. I’m going to break the spell. I’m going to write like a child cries, that is: it doesn’t cry because it’s sad; rather, it cries to inform, peacefully.

[Published in La Gaceta de Tucumán, San Miguel de Tucumán, February 22, 1970.]

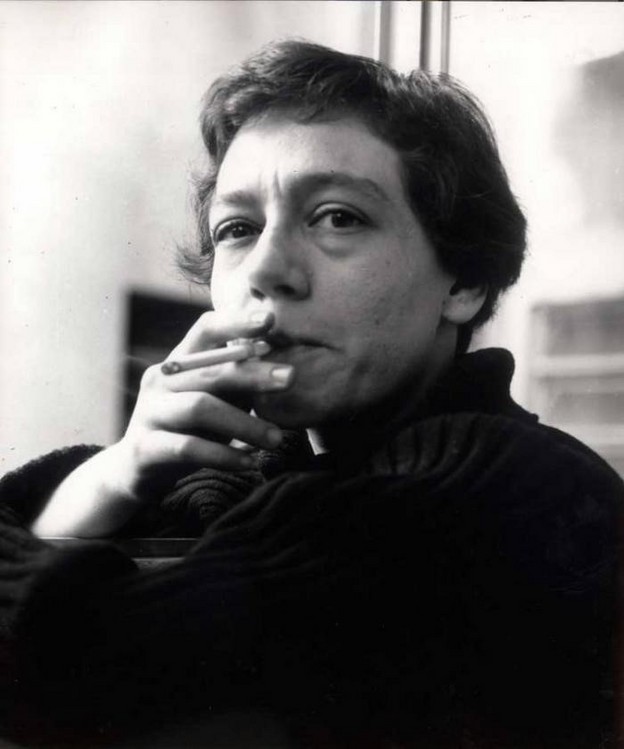

[COMMENTARY: Flora Alejandra Pizarnik (1936–1972) was born to Russian Jewish parents in an immigrant district of Buenos Aires. During her short life, spent mostly between Buenos Aires and Paris, Pizarnik produced an astonishingly powerful body of work, including poetry, tales, paintings, drawings, translations, essays, and drama. From a young age, she discovered a deep affinity with writers and artists who, as she would later comment, sacrificed everything in order to “annul the distance society imposes between poetry and life.” She was particularly drawn to “the suffering of Baudelaire, the suicide of Nerval, the premature silence of Rimbaud, the mysterious and fleeting presence of Lautréamont,” and, perhaps most importantly, the “unparalleled intensity” of Artaud’s “physical and moral suffering” (“The Incarnate Word,” 1965).

Like Artaud, Pizarnik understood writing as an absolute demand, offering no concessions, forging its own terms, and requiring that life be lived entirely in its service. “Like every profoundly subversive act,” she wrote, “poetry avoids everything but its own freedom and its own truth.” In all of Pizarnik’s writing, this radical sense of “freedom” and “truth” emerges through a total engagement with her central themes: silence, estrangement, childhood, and — most prominently — death. An orphan girl’s love for her little blue doll pumps death gas through the heart of her avatar. The garden of forgotten myth is a dagger that rends the flesh. A grave opens its arms at dawn in the fusion of sea and sky. Every intimate word spoken feeds the void it burns to escape. Pizarnik’s writing exists on the knife’s edge between intolerable, desolate cruelty and an equally intolerable human tenderness. As she remarks of Erzébet Báthory in “The Bloody Countess”: “the absolute freedom of the human is horrible.” And the writer’s task, she added in a late interview with Martha Isabel Moia, is to “rescue the abomination of human misery by embodying it.”]

N.B. Additional poems by Alejandra Pizarnik appeared here on Poems and Poetics, and her important essay on Antonin Artaud appeared here.

Poems and poetics