Toward a poetry and poetics of the Americas (18): Faustino Chimalpopoca

From 'The Náhuatl Exercises'

[Another excerpt from a work-in-progress, coedited by me with Heriberto Yépez and John Bloomberg-Rissman: a transnational anthology of the poetry and poetics of North and South America “from origins to present,” to be published in 2020 by the University of California Press. (J.R.)]

from the Náhuatl exercises

First Exercise

I am human, a person.

You are a boy.

He, or she, is good.

We are strong.

You are plumed,

Or feathers have been glued to you.

They are crying.

This woman is not good:

She is a witch.

These men have one-arm.

Who told you this?

Nobody.

This young girl is one-eyed.

What are you doing?

Nothing.

I am only speaking.

To whom does this cape belong?

It’s mine.

To whom does this book belong?

It’s the young girl’s, or

the girl owns this book.

Various exercises

Good morning, how are you?

Good, thank you.

¿How was your God-night (material translation)?

With your mercy, it was a quiet night.

How is the great lady?

With good health for now.

I am very happy to hear this.

How are the kids doing?

More playful with each day.

God keeps them.

Where are you going, sir?

I am going to the house

Of our Virgin Mother.

I hope God gives you a happy trip.

I hope so, sir.

Speak some Mexican

I want and don’t want to speak

like an Indian

Why don’t you want it?

Because when I speak in such a way

Those who are called people of reason

Immediately laugh at me.

What can one do? Such is what

ignorance requires.

But how is that foreigners don’t mock me?

Because they know what they do.

And is it difficult to speak nahuatl?

I think it’s the same as other languages:

for some is difficult, for others is not.

Go to the plaza and buy some dark zapote,

some rough zapote which is called mamey

and chico zapote.

And if there is none, what should I do?

Immediately return here, and I will tell you

What to do then.

You will get mad at me.

I don’t get angry unless you hide from me.

You say so but I never really done that.

Do you remember when I found you

At the kitchen at your knees in front of that guy?

No! I was only praying!

Yes, really, in front of Little Fagot.

Where can I get big fish?

Maybe at the plaza.

And not in the street?

They say sometimes you can, yes.

But where can I always find big fish?

Ha! Ah! Ah! How should I know?

Your face shines.

Why is this? I am not sure.

Because you washed it.

An excellent thing to do.

Yes, in that way you will be clean.

Don’t shame me.

Time to wake up, sir.

Yes, I see.

By any luck are you getting up?

Not yet, it’s too cold.

Yes, days have been cold.

Bring me my shoes.

Which ones? The yellow or the black ones?

The yellow ones.

How can you use those to go to Congress?

It’s not your business, bring them to me.

Don’t you see, sir, that people will laugh at you?

No, because I am happy now

And I will go out as I wish.

Then I should also let my hair the way it is.

Have a great day, dear lady!

How has your god-given-day been to you?

Good, with God’s favor.

I am very glad to hear this.

How is your lord?

How is he feeling?

He’s better now.

What happened to him?

He had a big cough.

This sickness is around now.

What did you give him to drink?

Some tejocote water.

That is good, mainly

When is lukewarm.

Translation from Nahuatl-Spanish by Heriberto Yépez

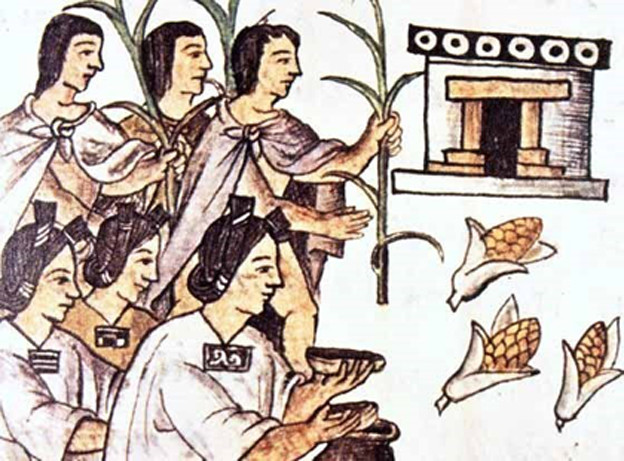

commentary

Faustino Galicia Chimalpopoca (1805–1877) was a Nahua translator and notorious scholar. He belonged to several intellectual circles in Mexico, though partly because he served Maximiliam I and partly because of mestizo racism against native scholars, he disappeared from the literary and intellectual record. Until now, literally nobody has become aware of the literary nature of what he called “Exercises,” which he placed as supposedly bilingual (Nahuatl-Spanish) reading and comprehension exercises between lessons in his grammar Nahuatl manuals. Some of the now canonical sources from the Nahuatl corpus (including the copy of the Cantares and the Chimalpopoca Codex named in his honor) where transcribed and originally translated into Spanish by Chimalpopoca. He had a very distinctive view of nahuatl and a very idiosyncratic way of both disguising his writing as pedagogical material and hoping more careful readers identify he was experimenting and playing with writing and the international literature of his time, which he knew both in Mexico and even probably from one travel he made to France. Much of the information on his life is now lost, but the satire, parataxis and constant reference to genres such as Huehuehtlatolli, nineteenth-century manuals of good manners, scholarly discussions about Nahua culture, and urban popular language, were combined by him to build a unique poetical language, with no comparison with what more traditional poets were doing in Mexico then and elsewhere in this way. Chimalpopoca was a Nahua early avant-garde poet. (H.Y.)

Poems and poetics