We peer through various portals

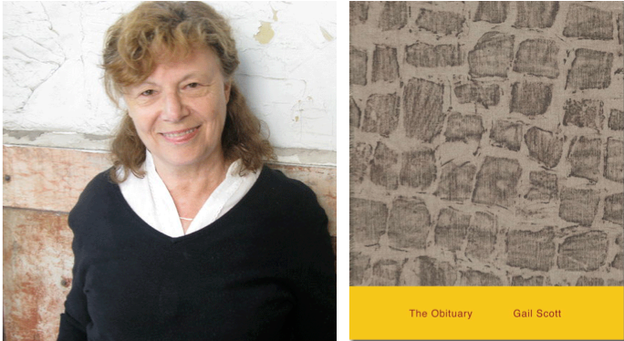

A review of Gail Scott's 'The Obituary'

The Obituary

The Obituary

Gail Scott’s The Obituary occupies and animates the tantalizing space of the in-between. Between English and French, poetry and prose, lurid gutter noir and stylish Hitchcockian thriller, Scott’s novel (though it is in some sense an injustice to characterize it simply as a novel) inhabits these elusive gaps, experimenting at every turn with subjectivity, grammar, and the poetics of lapsus. Set in Montreal, The Obituary reflects the city’s gleeful heterogeneity — its negotiation of old, new, and postmodern, francophone, anglophone, allophone, and native cultures. The novel’s main protagonist, I/Rosine/Rosie is haunted by the latter and by the suppression of a secret history — her Métis origins — in her journey from rural Alberta to Montreal, Quebec and present-day Mile-End, a culturally diverse neighborhood at the heart of Montreal’s artistic community. Scott’s previous novels, especially Heroine (1987) and Main Brides (1993), are likewise about Montreal as signifier: neither European nor American nor conventionally Canadian, nestled on the fringes, happily bridging a French sensibility for the subtle and the erotic and a North American desire for openness — a metropolis that, like Scott’s writing, is polyvocal, swerving, and elegantly eclectic.

The particular vibrancy of Mile-End, with its working class history, bohemian aura, and quintessential architecture, is as much a character as it is a backdrop for The Obituary’s plot — an oblique murder mystery, for which the French term intrigue is, not accidentally, the mot juste. Scott presents us with a matrix of narrators, scenarios, histories, and dialects, all tinged with amorous conspiracy. We are made to inhabit the often voyeuristic perspectives of its many narrators — I/Rosine, who rides the bus through the city soaking up its “little conflagrations” (7); an anachronistic gendarme who obsessively tracks Rosine’s comings and goings; the multiple, ghostly voices of her mother, Veeera, Uncle Peeet, and Auntie Dill; MacBeth, the dubious neighborhood psychoanalyst; Face, the all-seeing visage behind the blinds at 4999 rue Settler-Nun (the triplex at the novel’s center); “I/th’fly,” a lascivious fly-on-the-wall, whose multilensed eyes probe when others would turn away; and the elusive Basement Bottom Historian, who “guards against overinterpretation” (10), often in the footnotes. From the outset, then, The Obituary asks us to immerse ourselves in a delightfully tangled sonic landscape whose silences and gaps are as telling as its declamations — a symphonic reading environment in which we loiter hoping to discern the “tale encrypted mid all these future comings + goings of parlour queens, telephone girls, leather divas, and Grandpa’s little split-tailed fis’” (6).

But it is Scott’s clever use of the triplex as architectural signifier, historical marker, and poetic space — “Is not landscape the supreme historian?” a narrator asks (42) — that ties these many threads together. The triplex at 4999 rue Setter-Nun (a fictional address) becomes the literal and figurative space of intrigue in The Obituary, a three-dimensional palimpsest that defines, even as it is defined by, the characters who inhabit its walls. As one of Scott’s narrators puts it, “If material conditions shape the spirit, we may empirically declare the Triplex the place where what is happening is the place” (16). Indeed, the three-dimensionality of the triplex, “awkward as 3-D set of Dial M for Murder” (18), is echoed in the structure of the novel, as layers of language accrue and it comes to resemble a relief sculpture — a surface we have chipped away at, but whose depths we have not quite set free. In this respect, its murder plot might be read as an intentional red herring. Solving the crime (or even determining of what the crime consists) is not nearly as important as the various ways of seeing/sleuthing enacted throughout the book, and the search for clues, i.e. the experience of Scott’s experimental style, is far more captivating than the brute information — the corpse — we eventually discover. A perfect example of The Obituary’s franglais sensibility, each errant “clou” we stumble upon — “Here is a clou in th’case.” (71) — is literally one more nail in the coffin. As readers, then, we peer through various portals — the doorways, the blinds, the “oeil de beouf” windows, and an entire section entitled “VENETIANS THAT EVEN PRIVATE EYES HAVE TROUBLE SLEUTHING” — all of which happily conceal as much as they reveal.

Yet, the novel’s experiments with the lure of language, its “slippy-slidey sentences, switching this way + that” (33), do not amount to wordplay for its own (beautiful) sake. Just as the Mile-End triplex encodes a history of its many renovations, The Obituary constantly revises its own story and method, “little by little revealing why we meandering in speaking” (33). This process of revision gestures toward a “future novel space” (24) that Scott portrays as a prosthesis for the past, a scarred signifier that takes the place of a history that was never written: the novel’s indigenous secret, its “Indig-nation” (56). In this way, the textures of everyday life and its intrigues, so expertly rendered through the eyes of Rosine and her cohort of narrators, are emblematic of the kinds of diagetic repression that allow her (and her family, her city, her nation) to not-quite-forget, for “Do not skyscrapers bear, deep within, straw huts? The person, her ancestors” (115)?

Ultimately, then, Scott’s novel performs the desire to uncover that which has been “nearly totally felt-pen redacted” (61), the crucial details — shards, flashes, and “scintillas” — that explain the present via the “past + its objects, as saying great Walter B” (116). Benjamin, who was an interlocutor in Scott’s My Paris (1999), appears in this novel as a ghostly reminder of these chance interactions between surface and depth and of what Benjamin calls our “tenden[cy] to deflect the imagination … back upon the primal past.”[1] Scott’s Montreal, like Benjamin’s Paris, vibrates with our “collective pathos” (145), and The Obituary, in the process of writing that collective history, invents a new vernacular for its (and our own) hybridity.

1. Walter Benjamin, “Paris the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” The Arcades Project (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002), 4.