We have a choice

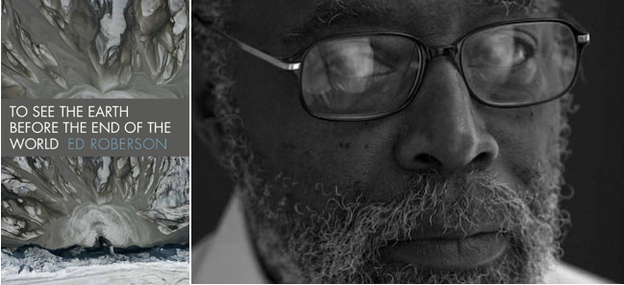

A review of 'To See the Earth Before the End of the World'

To See the Earth Before the End of the World

To See the Earth Before the End of the World

Ed Roberson’s newest collection, To See the Earth Before the End of the World, exudes an immediacy, an unmistakable sense of urgency in its simultaneous lament of and call to arms for the contradictory world we inhabit. In this, Roberson’s ninth collection, the Earth and the world are held up as rings of a Venn diagram, overlapping but not interchangeable, together representative of humanity’s existence: both shared and experienced very much individually, a communal phenomenology, a physical, public place in which the private dramas of our lives play out.

In his previous collection, The New Wing of the Labyrinth, Roberson meditates at length on the prospect of death in the experience of the individual, a personal shade always present, an ending haunting the story of one life entire. Here, however, Roberson preoccupies himself with the end of humankind in general. In the title poem of the collection, he chronicles “the world’s death piece by piece,” highlighting the difficulty of negotiating a relationship between the extremes of public and private, objective and subjective, past and future: “Some endings of the world overlap our lived / time,” he writes, “[…] the five minutes it takes for the plane to fall, / the mile ago it takes to stop the train.” Janus-like, these poems witness our personal losses and our “small human extinction,” irrevocably tying the two together. “Hunting the bear,” Roberson reminds us, “we hunt the glaciers.” In our individual deaths, we are heading toward the ultimate end of our species.

In this notion of the small and large bound up in one another, of one emblematizing the other — the deaths of individuals entailing that of species, the destruction of a species entailing that of a planet — we are reminded of John Donne’s Meditation xvii: “any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind; And therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.” Just as Donne’s writing does, the poems in To See the Earth Before the End of the World struggle with the role of the individual in the community and the corresponding, congruent role of the community in the world, temporally and spatially. Ralph Waldo Emerson puts it another way: “If the whole of history is in one man, it is all to be explained from individual experience. There is a relation between the hours of our life and the centuries of time.” To Donne, Emerson, and Roberson, the individual’s experience is emblematic of all human history, and vice-versa.

Roberson often works white space into his poems, suggesting lacuna in the text, the blank spots on the phenomenological map corresponding to unfulfilled human needs and desires. In “The World, Then,” Roberson contemplates “That lonesome whistle silence of / stars”— that is, the need for other people — whether it’s

Undoing or one motion through

The Milky Way folding its complexity? The dark drawer.

It’s over our head

But (a small thing) lose your balance, you fall

into that dark shirt never pulled off your head.

In “String Drawer,” a poem from his previous collection, The New Wing of the Labyrinth, Roberson evokes the trail of string used by Theseus to navigate the Minoan labyrinth:

The saved string

drawer of snakes

opens out of the stone

pile at the end of the yard

that supplies

Spring.

In both instances, he re-grounds the whole of nature — the eternal, the fantastic — in the quotidian, using something as simple, ubiquitous, and domestic as a drawer to encompass it. Whether it’s anguish that “wails from a simple single teapot” (“Teapot Boiling, How to Begin the Day”) or “a tree that has taken / a bullet from the civil war” (“What the Tree Took, on the Table”), Roberson uncovers the emotional shrapnel embedded in the material world by virtue of people living in it, simultaneously shedding light on the artifacts of the individual human life as well as those of an entire culture and civilization, the “fired clay jars. // Each note a jar with this thickness — / a fingerprint on the unseen inside / surface out— of the touch / of silence” (“Song”).

Roberson’s work comprises an elegant and perpetual memento mori, and in To See the Earth Before the End of the World he provides the reader with a kind of ontological landscape — life, death, apocalypse, and afterlife — as a reminder of one’s paradoxically ephemeral, local life and the more lasting, overarching effects it can have on the lives of others. Urging us simultaneously to witness the world, to remember it, as well as to preserve it for future generations, these poems illuminate the dim and uncertain reaches of the human preoccupation with life and its ultimate end. We “don’t / know how death counts the rings / from trees to clocks, / species to singled soul / at its hour,” Roberson writes, “or on history’s days we die all at once.” He teaches us that we know how to behave, we know how to preserve creation rather than destroy it, and that, ultimately, we have a choice — and further, inevitably, “hunting that bear, / we hunt the glacier with the changes come / of that choice."