Ways to be

A review of 'Kindergarde'

Kindergarde: Avant-Garde Poems, Plays, Stories, and Songs for Children

Kindergarde: Avant-Garde Poems, Plays, Stories, and Songs for Children

“They don’t always do as they are told or follow the instructions about how to act on paper or in society. They remind us that there are lots of ways to be,” editor Dana Teen Lomax says of the contributors to Kindergarde: Avant-garde Poems, Plays, Stories, and Songs for Children (viii).

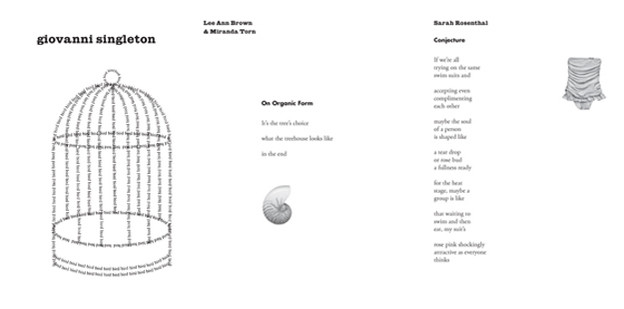

At first glance, the 9x12 anthology — I’m thinking of its sheer bulk, mustard-colored cover, and blocky title font — might be taken for a phonics workbook from the 1970s. Yet Kindergarde illuminates literacy of another kind. It presents myriad genres, arrangements, conventions, and experiments: tales, nursery rhymes, catalogues, abecedaria, anaphora, collaborations, songs, fables, performance pieces, plays, lullabies, writing exercises, epistles, lyric essays, visual poems, drawings, photographs, a palimpsest, and an onomatopoeic dedication to Nietzsche. The reader is also a contributor to Kindergarde: the book invites and provides room for original writing and artwork.

Kindergarde successfully reaches the anthology’s intended audience of children as well as a wider audience: readers of avant-garde literature. Once adult readers see the contributors list, which includes Charles Bernstein, Christian Bök, Wanda Coleman, Juan Felipe, Kenneth Goldsmith, Lyn Hejinian, Cathy Park Hong, Harryette Mullen, Eileen Myles, Leslie Scalapino, Evie Shockley, Juliana Spahr, Anne Waldman, and Rosmarie Waldrop, they will likely proceed to the checkout line. I did.

The German title evokes the European avant-garde children’s literature tradition. For more on Kindergarde’s predecessors, I enjoyed critic Philip Nell’s blog post on the 2012 Children’s Literature and the European Avant-Garde conference. He provides illustrations and cover art from contemporary and modernist texts as well as insightful commentary.[1]

In the vein of European avant-garde children’s literature, Kindergarde offers social and cultural critiques: education, gender, race, class, and ethnicity are among the topics examined. Yet, the makers of Kindergarde seem to collectively believe that kids get schooled enough. Thus, the experimental surfaces are so textured, the language (and imaginations) so plastic, the collection as a whole so restless that the critiques present as “ways to be” or choices rather than didactic lessons. For example, Robert Glück and Jocelyn Sandburg’s satirical play (with photographic illustrations), “Precious Princess, or, PIG Speak,” features a finger puppet Sleeping Beauty laying an egg. And why not? As Balso the Knight tells the new mother, “You may not have a head, but you have a big pink egg to hatch” (72). Of course, Precious Pig and Sock Monkey then host a poetry salon in an unexpected send-up of the creative writing workshop.

My favorite of the collection is Bhanu Kapil’s “The Night I Walked into the Jungle, I Was Nine Years Old [With: Accompanying Footnotes],” with mad footnotes, that is: more extensive than the text they annotate. The footnotes add dimension and texture to her lyric sentences, as Kapil moves from reverie to direct address to reverie: “But you are probably still thinking about the whales and the ocean and the Maoris and all the amazing and difficult and dark blue and glittery things of the Southern Hemisphere, which are hard to face with any precision. Precision is when you are not thinking about the future. My grandfather used to tell me that” (94). The central narrative — we are told that readers who want to hear another tale, one about “Hanuman, the famous Monkey King,” may email Kapil — recounts a very long walk the writer took with her grandfather. After they leave the family home in Nangal, India for the surrounding forest, the two become runaways (by whim) for a single night. The grandfather relays gentle wisdom. They encounter various scenes and characters — a giant puddle, nomads, a chess match, and a white horse. The account itself is an exquisite wandering — Kapil wending her way through a variety of associations.

“Ways to be” inform the grammar and rhetoric — the repeated modal verb may and the self-definition trope — of Rosmarie Waldrop’s “Apricot Madness, A Song for Christopher Montgomery.” Waldrop’s poem opens:

My head may be a cabbage

my heart an artichoke

my face a mouldy kumquat

my left eye a bulging yoke (109)

The prosody suggests yet defies convention. “Apricot Madness” consists of ten quatrains and a final monostich. Three-beat ballad stanzas are unbalanced by one and two-beat refrain stanzas. While ballad rhymes are whole (wire/fire, ham/jam, stale/hale), the insistent anaphora diminishes in the second half of the song. In the final stanza, Waldrop adopts the present progressive and, for the first time, joins the first and third lines with end rhyme, albeit slant:

I’m turning into a gargoyle

getting drunk on rain

but the moon is no cold pineapple

as long as I got my brain

Eileen Myles’s unpunctuated, fourteen-word, eight-line “Jacaranda” conflates our man-made prosody jargon, “the feminine / of feet,” with the natural world that she can “have” — the jacaranda, “a lavender / tree” (111). Joan Larkin’s brief play, “If You Were Going to Get a Pet,” takes place in winter on a moving train during Child and Parent’s story time. The static setting, terse dialogue, and postapocalyptic details make of the bedtime story a Beckettian cautionary fable. Here is a world where children are cared for and stalked by Black Dog, where children wait “for [their] mothers to come,” mothers who “sent letters on thin blue paper” (129).

What else in Kindergarde reminds me “that there are lots of ways to be”? Susan Gevirtz’s hybrid excerpt from Streetnamer on the Moon;Reid Gomez’s domestic narrative, “Slices of Bacon”; Brian Strang’s Gothic visual poem; Sawako Nakayasu’s prose poems; R. Zamora Linmark’s fantastical “The Archaeology of Youth”; Jaime Cortez’s irreverent short story, “The Jesus Donut”; an open field excerpt from M. NourbeSe Philip’s ZONG!, and “Wipe That Simile Off Your Aphasia,” Harryette Mullen’s catalogue of incomplete similes.

Most importantly, what does my three-year-old think? “A Dog is a Wolf is a Dog,” from Andrew Choate’s Worm Work, is her favorite selection:

Sometimes my sneezes

smell like my dog

after he’s rolled around

on a rotting bird carcass —

I think it’s a good thing. (30)

In just twenty-three lines, Choate covers much of the organic material that most delights my daughter — dead things, parasites, blood, kiwi, frog pies, fish, and antennae. As an added bonus, the poem alternates between the voice of the poet-speaker and the Seuss-y child sass of the penultimate stanza:

Put a fish in a glass

Wear it for a watch

A wrist wash fish watch

Water bubble time notch

In the white space to the right of Choate’s poem float three overlaid figures of a dog in midstride, hind legs and partial forelegs visible. When asked for some critical insight on the piece, my daughter proffered, “Dog butt.”

“See you later,” reads the final page of Kindergarde. Under the phrase is the figure of a magnifying glass. Yes, this anthology invites young readers, all readers, to not merely see the depicted worlds of the authors but to inspect, question, and remake those worlds. Who needs “follow the instructions” anyhow? Why not write them? Why not erase them? Better yet, ![]()

1. Philip Nell, “Avant-Garde Children’s Books; or, What I Learned in Sweden Last Week,” Nine Kinds of Pie, October 5, 2012.