Unraveling tongues

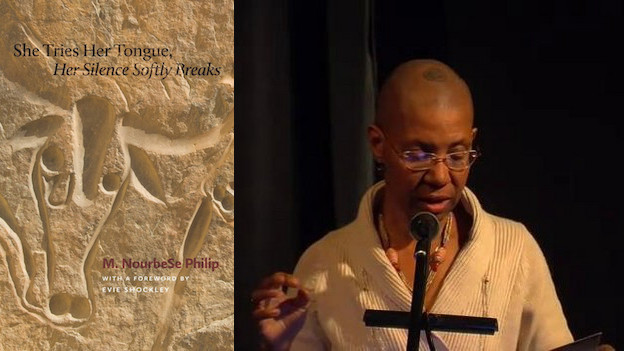

A review of 'She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks'

She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks

She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks

If she does not ravel and unravel his universe, she will then remain silent, looking at him looking at her. — Trinh T. Minh-ha[1]

I first encountered M. NourbeSe Philip’s poetical interruptions three years ago, in a course taught by Tisa Bryant called Unnamable Texts. We spent time with “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” which is a sequence from her 1988 collection She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks. My memory of this poem is bodily. Part of this is due to how we read this piece; not only silently to ourselves, but also following along to a recording of Philip performing the poem. Throughout her delivery, she subtly elongates the word language until it becomes a cry, a tender wound, throbbing:

lan lan lang

language

l/anguish

anguish

english

is a foreign anguish[2]

Philip’s collection implodes the English language’s status as essentially universal, objective, ahistorical, standard, benevolent. The poems counter this view by revealing in English what it works hard to conceal: its intimate entwining to colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy, the creation of the Other. The text inquires, “From whose perspective are the lips of the African thick and her hair kinky? Certainly not from the African’s perspective” (86). For an African Caribbean woman writer inhabiting and moving through colonial(-haunted) spaces, language emerges as a “site of memory,”[3] holding deep beneath the surface legacies of terror, subjugation, and denial. Where does a language place you? How to address space in an English heavy with dispossessions? In the essay “The Absence of Writing or How I Almost Became a Spy,” included as an afterword, Philip meditates on the echoing ramifications of the linguistic devastation experienced by Africans abducted to the New World. Their arrival to Caribbean and North and South American lands signaled a shattering departure from consciousnesses, culture, histories, lineage, memories, agency, spirit, notions of belonging. A rupture and dislocation from time, self, and being. African tongues and expression became fugitive, mangled, forbidden. To enter the colonizer’s language was/is to enter a consciousness hostile to your multifaceted existence, an environment flooded with acts of careless renaming, stereotyping, indifference. Philip approaches silence not just as absence or loss, but that which is misunderstood, discounted, or unsayable:

In the vortex of the New World slavery, the African forged new and different words, developed strategies to impress her experience onto language [...] Nouns became strangers to verbs and vice versa; tonal accentuations took the place of several words at a time; rhythms held sway. (83)

The Caribbean Demotic. Patois. Creole. AAVE. These percussive speeches enact grammar gestures more common to West African languages. From formal English’s perspective these ways of expressions can only be (mis)seen as illiterate, broken, bad, shameful. But within and without the space of the text English is tainted by a “colonial order,” which necessitates a whirling trial before a trueness can be fully experienced. To focus on the supposed “correctness” of the demotic moves you further from the point: what were the historical conditions that made its creation compulsory? The subversion of European languages presented the captive African the means with which to “impress her” subjectivity unto a language hinging upon her very nonbeing. In this way Caribbean languages can be said to function as “demonic grounds,” a term used by Katharine McKittrick, which references the essay “Beyond Miranda’s Meanings: Un/Silencing The ‘Demonic Ground’ of Caliban’s ‘Woman’” by Sylvia Wynter.[4] In McKittrick’s text, she expands upon Wynter’s definition of the demonic, giving breath and shape to the ways in which black women’s (bodily) subjectivities disrupt and unwrite traditional notions of geography, history, language, being, time. Their experiences through and beyond the transatlantic slave trade map oppositional narratives that speak back to the racist-sexist systems that work to keep them “in place”[5]: as commodities, as footnotes, as invisible, as deviant. In the confines of “his universe,” her body becomes the “site through which sex, violence, and reproduction can be imagined and enacted,”[6] wherein the “madness”[7] of European domination renders her point of view as both knowable and drowned. Demonic grounds enact a portal whereby the unseeable, the improvised, the gnarled take precedent over the classifiable, hypervisible, profitable.

When attached to issues of language, the demonic percolates a looping image of the complexities confronting Afro-Diasporic writers who “wish to make a home” in the colonizer’s language, or as the text names it: father tongue. Philip’s words, restless, ache: how to return to a mother tongue that has been displaced? The text’s first poem sequence, “And Over Every Land and Sea,” begins in frantic search. Roman goddess Ceres has been transplanted to the Diaspora, driven “grief gone mad with crazy” (2) over the abduction of her daughter Proserpine. Over the course of seven poems, mother and daughter circle around each other’s memories of what seems to be unknowable. Ceres searches, going as far up as “where north marry cold I could find she — / Stateside, England, Canada” (4) — locations in various knotting ways connected to black women’s histories and movements, silences and forced placelessness. The “I” in these poems, and throughout the collection, holds the capacity for many voices at once. Ceres inhabits the numerous migrations/interruptions of the black woman body and reimagines a recombinant origins story from “the last place they thought of”[8]:

to where never see she:

is “come child, come,” and “welcome” I looking —

the how in lost between She

and I, call and response in tongue and

word that buck up in strange;

all that leave is seven dream-skin:

[…]

seven dream-skin and crazy find me. (5)

Out of silence and “memory half eaten / and half hungry,”[9] the text addresses unseen locations that nevertheless vibrate with dilemmas of control, reclamation, and unknowing. Tongue and word attempt to conjure “the how in lost between She”; language attempts to fill what has been swallowed up by gaps. What remains of their dance are “dream-skins,” poems motioning toward the unspeakable, unimaginable, unresolved. Ceres’s search resonates by frustrating accepted beliefs around the linearity of time and space. For the Afro-Diasporic woman, time is full of abductions and rerooting, intrusions and regeneration, slips and “dis place.”[10] Ceres finds Proserpine not by locating her physical body, but through a creative engagement with the spaces that hold the (intentionally) lost and forgotten. Although this act does not rid Ceres completely of her devastation, it does provide grounds to release her particular expressions.

Starting with “Discourse on the Logic of Language,” the text marks a shift that continues for the rest of the collection. The seeking lyrical voices guiding the first four poem sequences give way to a burst of polyvocality reorganizing how we approach and understand words’ place and movement on the page and beyond. These poems bring together, interrogate, and warp multiple discourses: national, poetic, educational, legal, mythic, linguistic, scientific, archival. If your body is threatened and/or diminished, what does that do to your sense of expression?

“Discourse” turns a yearning for a mother tongue into a circling contemplation of belonging, recovery, and traumatic remains. Throughout, expression is threatened by dominant discourses (legal, anatomical) that wish to limit the validity of an African positionality. In “Universal Grammar,” Philip plays with the form of a linguistic workbook, uncovering the violence lurking behind the distracting sheen of universality. The left side of the page contains parsing exercises which pull from words that appear in the poems found on the right side. Interrupting the poems are excerpts from seminal texts on language; in all capital letters, these voices describe “the constraints of universal grammar” (39): as innate, as unaffected by consciousness. Language is divorced from the body and its surroundings, becoming instead a rote instrument. In order to break her silence, the speaker imbues her language with historical realities and reimagination. Parsing, an activity done in an effort to “know” a sentence, is recontextualized as an act of aggression: “the exercise of dis-membering language into fragmentary cells that forget to re-member.” The space of the page becomes charged with what should not exist:

the smallest cell

remembers

a sound

(sliding two semitone to return

home)

a secret order

among syllables

Leg/ba

O/shun

Shan/go (37)

English carries remnants of the auction block, bodily punishments, dread, but at the same time there can be space for spiritual guides, ancestral strength, future possibilities. A sound, a physical reaction, brings to awareness other meanings laying outside the gaze of dominant discourse. By entwining body and language, rather than seeing them as exclusive, the text envisions another way of organizing place, movement, and memories.

What to do with a language that dis-members you? The text is ultimately uninterested in recreating slavery as a digestible, past, knowable occurrence. To do so would be akin to trapping it in an unmovable silence. Philip names the transatlantic slave trade as a point of rupture, one whose effects still reverberate. These experiences cannot continue to be narrated solely through our “politely but vehemently racist” (91) discourses. If English refuses and simplifies her subjectivity, then Philip will remake English as she experiences it: contradictory, an assault, a map, in flux, an opening.

1. Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), 47.

2. M. NourbeSe Philip, She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2015), 32.

3. See Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir ed. William Zinsser (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 83–102.

4. Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xxv.

7. Édouard Glissant, Carribean Discourse: Selected Essays, trans. J. Michael Dash (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 160.

8. McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, 37.

9. Leslie Catherine Sanders, ed., Fierce Departures: The Poetry of Dionne Brand (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2009), 2.

10. M. NourbeSe Philip, “Dis Place: The Space Between,” in A Genealogy of Resistance (Toronto: Mercury Publishers, 1997).