Symptoms and sources

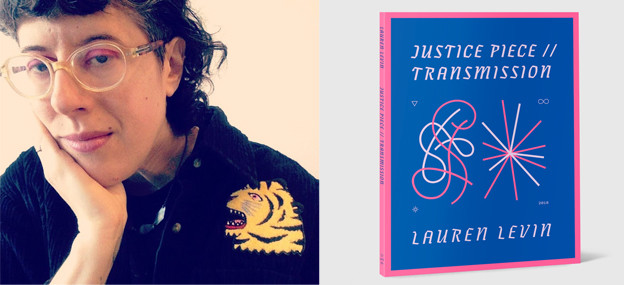

A review of Lauren Levin's 'Justice Piece // Transmission'

Justice Piece // Transmission

Justice Piece // Transmission

Lauren Levin’s second book, Justice Piece // Transmission, is comprised of two essayistic poems that continually untangle and reconstruct the web of contradictions that shape the speaker’s ever-complex, and always self-questioning, inner narrative. In both pieces, Levin traces anxiety back and forth from its source: the social, material fabric that challenges any “total” understanding of what it means to be a person — a queer person — and a queer gender-fluid person — in the world right now. In a voice of wholly sincere, dialectical panic, Justice Piece // Transmission resists closure, and fluidly navigates the boundless intersections, curves, and gradations of public and private identity. At the same time that Levin constantly questions their own assertions in the moment, they continually return to the text’s center: the intersection of queerness, feminism, and labor, especially in terms of care work, which is both undercompensated and underrecognized as an essential function of capitalism.

Levin, a New Orleans native who uses she/they pronouns, is no stranger to engaging poetry as a tool for radical change: in the past, they have served as editor of Poetic Labor Project, and are a current columnist-in-residence at SF Moma’s blog, Open Space. Levin has also written about the genre-bending work of living poets and artists whose identities are often excluded from the traditional literary canon. Justice Piece // Transmission is Levin’s second full-length book, published by Oakland-based queer press and performance collective Timeless, Infinite Light, who aim to unsettle the traditional literary canon. Their website reads: “We believe in the radical potential of collaborative, hybrid, and embodied writing, and promote work that resists structures of oppression, both in form and content.”

The first of the two eponymous poems in the book, “Justice Piece,” takes place in the frame of the question “what is justice?,”[1] which a friend asks the speaker over an instant messaging conversation. The speaker never promises to resolve it entirely, or even remotely — instead, they take the time to unravel the wide-ranging associations that arise in the question’s wake.

When I think “justice is served”

I think of what women do, serving, service work

But it’s interesting that this is an aggressive ‘served’ —

in the phrase “justice is served” there’s a missing object,

like, justice is served upon whom (13)

Is justice fair? As an exchange between two parties on opposite sides of a problem, under capitalism, the transaction inevitably favors the entity with more capital or social mobility. According to Etymonline, justice comes from the Latin iustitia, meaning “righteousness, equity,” and from iustus, meaning “upright, just.” Removed from context, the term implies equality, straightness, finiteness. In practice, justice occupies the space of paradox: the deeply entrenched and cyclical power imbalances of society eradicate any possibility of fairness.

When justice behaves as a procedure for maintaining or amending social order — and as a way of preserving the logic of the state — then naturally, this practice wouldn’t interrogate the material conditions or root sources that perpetuate inequality. Instead, the prevailing exercise of justice is to impose punitive measures (or possibility of rehabilitation, the success of which remains to be seen) that stem from the governing body, in order to treat the symptoms (but not the sources) of social wrongdoing. Even in supposedly anticapitalist communities, justice work often mirrors the system it attempts to rectify — late capitalist heteropatriarchy — which is why survivors take on the bulk of the labor in bringing justice to gendered violence, for instance. Even when harm is addressed outside of a system that was not designed to handle such complexities, the process of accountability still inherits its logic from the superstructure.

Observing this paradox of justice, Levin foregrounds situations in which harm reduction has fallen on women and gender-nonconforming people, in the Bay Area in particular:

It’s the question of who does the work.

I think about last summer. A number of men in the poetry scene

had perpetrated sexual violence. So many conversations:

what to do, how to let people know. How to not always be doing this

Some of the conversations were about restorative justice.

And though I’m against prisons, against cops

I felt angry. Angry about the work,

justice as another part of our care work:

taking the person who had done harm

and instructing them in that harm. Creating systems. Getting the mediators

the training and the skill-shares. The childcare and the snacks.

At cost to our lives and our work and our anger

asking ourselves that we be patient. (58)

“So much of what we see,” in “Justice Piece,” is the trauma the state afflicts, with disproportionate severity, onto the marginalized body. “I try to imagine justice as the opposite / of whatever the police do,” Levin offers (11). If history produces impenetrable structures and the reactionary logics that uphold them, then the police serve to protect the social contract and/or the status quo. As a paranoid, dysfunctional extension of the state, the police rely on ungrounded suspicions of misbehavior to justify violence against the most disenfranchised communities in America, while circumventing interrogation directed toward them. In America, an essential function of the police is to prevent unity and collective power among the working class, since this is exactly the kind of mobilization that would pose an immediate threat to the white supremacist structure that the police protect. So they impose violence onto those outside the margins of power — those who share a common enemy — by exercising brutality, intimidation, silencing, and incarceration.

If the police respond when institutional order is threatened, then they serve in direct opposition to queerness — a position that counters the logic of heteropatriarchy, whereby heterosexual reproduction, as well as heterosexual marriage, gives birth to labor and provides the basis of capitalism. Levin observes how police perform the role of a fearsome superfather, enforcing authority without pushback:

The function of police is to make violence always available

So the police are an authoritarian parenting fantasy

No counter-force, nothing asserting its own will (16)

With deep awareness of their own position of whiteness, Levin often returns to parenting while queer and radically, intersectionally feminist: “Andrea Liss says that motherhood is a problem that won’t go away, an embarrassment” (16). Like justice work, reproductive labor is both undervalued and overexerted — disproportionately on the part of women and gender non-conforming people — within the dominant culture. The care inherent to reproductive labor, as Levin suggests, serves in opposition to policing.

I stopped nursing her. Though she’s over two it feels sad to me,

sad not to feed. I can’t pacify her with my body

But now that a connection has been severed

She’s more affectionate, lies in my lap

head under my chin, sucking her thumb

and twisting the edge of my shirt

between the thumb and finger of her other hand (8)

Working through the speaker’s queerness, “Justice Piece” challenges the state’s operation of closed definitions, straight lines, and finality: “A crisis in who and what we value / A masculine-feminine-masculine body of resistance” (53). Here, Levin imagines a movement in which many bodies form a gender-fluid or genderless body of empowerment that subverts and unsettles oppressive binaries.

For Levin, cultural images provide a fundamental vessel by which to consider the factors of social position and identity. They energize inward-facing — often vexing — observations with an ocean of pop culture, media, art, and critical references: Shulamith Firestone, Andrea Liss, St. Vincent, mass Facebook group behaviors, online rants, and the agenda items of the Berkeley Parents Network, to name a few. Of all the cultural references that surface in Justice Piece // Transmission, The Rocky Horror Picture Show returns to the narrative most prominently, in various contexts: “Rocky Horror is one of those things that you can like as a pure sign — / when you’re a teenager who wants to show other teenagers / that you feel somehow other — you don’t have to let yourself know what it means / and yet it begins to hold meaning” (33).

As a film that provides for the speaker an early awareness of the possibilities of queerness and gender performance — a personal, cultural touchstone in many ways — Levin reveals how the meaning of film has transformed over the speaker’s life. From an experience that allowed for a deeply personal set of realizations to take place, to the knowledge that this, too, has been commodified (there is no ethical consumption):

The Rocky Horror Picture Show was a failure that became an advertising success

that became a social phenomenon that became a way of being together in public

that became a merchandising phenomenon that became a mechanism

people used to find each other

that became a cash cow for 20th Century Fox (61)

In keeping withthe vigor of “Justice Piece,” “Transmission” disfigures linearity, embraces every tangential instinct, and surrenders to new complications: a sentence breaks, and in the space where entropy almost happened, the poem is resurrected with a momentary obsession. If “Justice Piece” explores the problem of justice, then the second piece, “Transmission,” considers the speaker’s fixation with the body and its base functions: what the continual realization of one’s genderqueerness means for the body itself (as removed from the “construct” of the body), as well as the ability to produce orgasm, and the persistent hypochondria, rooted in family history, which disrupts the speaker’s performance in public life.

One symptom of hysteria: “a tendency to cause trouble for others.” I felt as

though someone had wrenched the dial, the homeostasis dial, and it had

broken off in their hand. All nature pulsates and vibrates with life. T comes

home saying “My teeth are worse. They’re crowding and bleeding.” (76)

“Transmission,” as the shorter and more essayistic sibling to “Justice Piece,” relates symptoms to their origins: a family history with mental health disorders, a “particularly Jewish form of paranoia” (97), and the diasporic trauma that lives on in the speaker’s body. In this piece, Levin observes how the family system, in late capitalist white supremacist America, produces a private-sphere breeding-ground for public-sphere oppression. Levin questions the racial and socioeconomic superiority that some members of the speaker’s family uphold, the gendering that occurs in the speaker’s upbringing, the pressure to perform the role of “a good Jewish girl” (80). “Transmission,” like “Justice Piece,” defines the speaker’s sharp awareness, and subsequent internalization, of the omnipresent injustices that disfigure their grasp on reality.

The night I thought I was having a miscarriage T and I lay next to each

other on the bed. I read a science fiction novel, deep in my isolate self

trying not to move. He slept a little, I checked for blood, we watched

a documentary about male body image. How contained the night was,

painful, boring, and intimate, being alone and with each other in pulses. (103)

Here, in keeping with the larger pattern of the text, the speaker observes and understands their body in relation to cultural signs and symbols. After watching the speaker experience the visceral horror of a possible miscarriage, we are relieved when the emergence of a science fiction novel, followed by a documentary, invites a space of temporary peace. A present, embodied intimacy permeates the text — the speaker rejoices in the company of loved ones, in a quiet room where nothing moves, nothing stirs, not even a thought.

In “Transmission,” the speaker remains curious about the intricacies of the gendered body. Instead of leaving us to recognize social conditions (and consequences) of sex and gender as the final questions of the body, Levin reminds us that the body — regardless of materialist frameworks — is a fascinating mechanism. By noticing how strange and incomprehensible the body is, “Transmission” is in some ways a celebration of bodily pleasure, bliss, and confusion, however twisted and impossible:

I feel intoxicated that this is possible: the eroticizing of pleasure in a body

like mine, specifically female. So that I begin to imagine the possibilities

for pleasure in my body as female or when it feels itself as male or

neither, or sometimes as nothing. But it makes me sad, too, to see an

image of that pleasure in a cultural object before I’ve even found it. That

it’s being sold, that it wouldn’t be a pleasure that couldn’t be sold. (100)

What is a pleasure center, and how does the defiance of gender assignment transform the impression of one’s own orgasm? How does gender-queerness or genderlessness expand or complicate the possibilities of pleasure? Like the earlier realization that The Rocky Horror Picture Show is not sacred, Levin expresses concern that even in moments of awe, the body is still co-opted and commodified into a product.

Levin’s work resists abstraction, and grounds itself in extreme realism by braiding (in the fashion of their first book, The Braid), contradicting materialist observations that overlap to the brink of almost-chaos. In just 110 pages, Justice Piece // Transmission spans memories and experiences of pop culture that have informed the speaker’s expansive sense or senselessness of identity, the reproductive labor of queer motherhood, hypochondria as a vestige of ancestral trauma, constantly distressing interactions with patriarchy, conversations with friends and community about building and repairing a world in which gender becomes central to the question of justice — that’s only a beginning.

Since Levin’s poetry occupies the concrete and corporeal dimension (as opposed to the metaphysical or sublime), it resists the need to beautify, embellish, or subvert reality. A passing manifesto reveals the underlying intention:

Make everything ugly

No aesthetics left

No mysteries left

Only problems (23)

Gestures of ornamentation, landscape, cleverness, and ephemera are absent in Levin’s writing, which prefers the gradations of antibeauty: an idiosyncratic, nonrational, and nonsyntactic force of reasoning. Justice Piece // Transmission transfigures the desperate urge to think through the matter quickly, because there is another question on the horizon, which will soon overthrow order and structure. The back-and-forth of one mind wrestling with infinite directions, without pausing, for the whole text, is uniquely Levinian. It is masterful.

1. Lauren Levin, Justice Piece // Transmission (Oakland: Timeless, Infinite Light, 2018), 8.